A

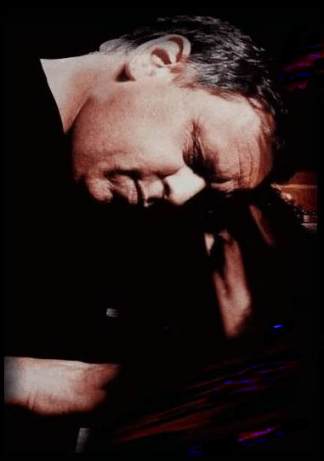

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH KENNY WERNER

I

am quite possibly the most boring person on the planet, well, at least

on my street, and I own a home in the burbs. Most people who have known

me even for a brief period could probably predict what color tie I will

be wearing with what suit and most of the ladies (I jest) know that my

answering machine message has remained the same for years. I have witnesses

to authenticate my theory. Maybe that is why the surprise of creatively

improvised music is so attractive to me. So it is a pleasure to present

to you, a candid conversation with Kenny Werner. His honesty is refreshing

in this day and age where it is protocol to blow smoke up everyone else's

ass. I bring it to you, as always, unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

KENNY WERNER: Well, it's a little than a lot of people. I grew up in a

very suburban environment and wasn't that aware of jazz except for a few

players. I was studying sort of a hybrid classical music, but I was also

good at pulling music off the radio, like pop tunes, Broadway show tunes,

and a little bit of jazz, but I wasn't really into it. And then when I

went to college, it was as a concert piano major. And when that really

didn't work out for me because I didn't find out until I got there that

I was not interested in that at all. I went to the Berklee School of Music

for a jazz school, but for me, it was more of what I already liked to

do, which was improvise. Even there, the allegiance wasn't so much to

jazz, but liking to improvise, which is the essence of jazz. Of course,

while I was there I got the bug to so many jazz artists and all my friends,

who became my network, were all jazz musicians and so I sort of slid into

that world.

FJ: Influences?

KENNY WERNER: You have to remember Fred that I did not come to jazz through

the jazz door. I, sort of, came in through the backdoor. I was always

an improviser. My influences and what I had done, largely, before I played

any jazz were things like weddings and casuals and those kinds of jobs.

My influences were unusual, ranging from romantic movie music and Broadway

music to pop tunes. I used to just improvise my own made-up concerto with

lots of dramatic moments and before I played jazz, that's mainly the way

I played. All the jazz players, as great as they were, didn't touch the

deepest spot in my heart until I heard Keith Jarrett. I don't think I

wanted to copy him, but he employed some aspects of music that were not

in use before he came along. When the music had gotten this icy kind of

harmony to it, he brought back, really some romantic type melody and ways

of playing on chord changes that I related to. He really used the whole

piano like a solo pianist. So I would say, the '70s, for example, Keith

Jarrett was the biggest influence for me. The funny thing about that was

I was playing what we call in New York, a club date in Boston, which is

like a wedding. They are not really clubs. They are really parties and

we called them GB gigs, general business. I was playing with an old Irish

bass player, who really couldn't play well at all. We were playing some

sort of party and while I was suffering through that gig in a nub state,

I was at Berklee at that time, he turns to me and he says, "Did you ever

hear of Keith Jarrett?" I looked at him wide-eyed and thought, "Why on

earth would he ask me that?" This guy probably would have been transcribing

Guy Lombardo. I said, "Well, of course, I have heard of him." At that

time, he was like my biggest passion. I was listening to him all the time.

He says, "Keith Jarrett used to work for me." I said, "He did?" Now he

didn't know Keith Jarrett as a jazz player. He didn't know anything about

his records or playing with Miles Davis. He said to me, "Keith Jarrett

was the greatest society piano player that I have ever heard." Funny thing

is, since that was what I had most done at that time, I understood the

connection between me and Keith Jarrett, how to play society cocktail

music. That was the difference between him and the other players. That's

not to say that I didn't love or was tremendously influenced by Herbie

Hancock, McCoy Tyner, Chick Corea, and Bill Evans. That was a very big

influence. I saw Bill Evans more times live than anyone else. But Keith

actually had something that was missing in everyone else's music that

I didn't even realize it until he came along. What happened was, he was

willing to incorporate more real elements that he had found by doing the

various kinds of jobs he did and didn't just switch over to playing jazz.

We became that connection, but Bill Evans was also a very big influence

on me.

FJ: You pointed out how you spent time playing society parties. It must

have been quite the learning experience hobnobbing with the rich and famous?

KENNY WERNER: Well, you really don't hobnob with them. You know what it

does Fred, it kind of, when I was younger I knew how talented I was. Wherever

I went I was the best player with relative little effort. I thought to

myself, "Why am I just playing these weddings and parties where you are

virtually ignored?" I played them from fourteen years old until I was

thirty. I thought God was playing some cruel joke on me. There are a lot

of dynamics to how a person ends up where they end up and of course, it

all changed. Being on those gigs, it was like they weren't even there.

Far from hobnobbing, they didn't know I was there, but in a sense, I didn't

know they were there either. I was just in my headspace, doing my gig,

watching the clock, hoping it would be over soon, and dreaming like so

many young musicians that someday I would be allowed to play with the

aesthetic that is closest to my heart and have people appreciate that.

FJ: Granted you expressed that you had come to jazz through other than

the traditional means, but when you actually got in through the door,

were you firm in the commitment that this was the path for you?

KENNY WERNER: No, I negotiated all the way through because I was always

afraid. There are people that have that vision and courage and I really

admire them. I was always afraid for survival and I don't even know where

I got that. I didn't come from a particularly poor background. I was always

worried, for example, if I had a gig with somebody, I would not say to

myself that this was not the type of music that I really believed in or

that this person doesn't use the piano in a way that doesn't honor me

personally. I would not say that. I would be saying to myself, "Oh, man,

he gets work. I need this person. I need this gig. If he uses me, I will

get more of a name." I would place a lot of importance on the person,

which would be the opposite of what you need to do. You need to place

a lot of importance on yourself and have faith that the right things will

come your way if you articulate that to the universe, so to speak. But

it took me many years to learn that, a lot of horror stories. There's

good gigs and good gigs. There are gigs that you totally share the aesthetics

with the person that you are working with and there are very good gigs

where you really don't share the aesthetics, but you feel like this gig

serves some purpose of the overall possibilities of what you are trying

to get to and so you hang with this form of strategy. Now that I look

back on it, I don't know. I know I have learned a lesson now to risk that

and try to stay with what you care about the most. Today, I put more of

my energies, even if I am not going to make money, it is clear to me that

what makes life vibrant is recording, playing, and composing the music

that comes through me and getting it out there. Maybe when a guy gets

half way through life, he starts to sense his mortality or something.

I don't want to waste time doing someone's gig that might lead to a spot

with this that could lead to a connection with that. I say screw it. The

rest of my life I just want to make my music. Some people come out of

college like that and I really admire their foresight and their faith

in themselves. Maybe it doesn't take faith. Maybe they are just not worried

about it.

FJ: How much time did you spend with Charles Mingus?

KENNY WERNER: Well, that is on my resume, but I was just on one of his

albums. And that was the only experience I had with him. In fact, it was

a room full of the greatest musicians in New York City and he wasn't dealing

with me that much.

FJ: How long was your tenure with Archie Shepp?

KENNY WERNER: I played with him for about three years. He was the first

professional touring band that I played with. I played with bands and

we did a night here and two nights there, but when I joined him, I finally

found out what the road was like, the six week tour, which is at the heart

of what the jazz experience is like, but it's so rare these days for so

many jazz musicians. I learned a lot. I learned a lot about the tradition

there. I learned a lot about playing forcefully, or as we say, burning.

I learned a lot about being thick skinned, not just from him, but from

the scene in general and just how to put your head down and fall into

your own groove and not worry about anything else. He could really cause

quite a commotion around him, but he would always be tranquil within himself.

I certainly learned that you could have that inner balance no matter what

kind of craziness is going on around you. I sort of have stories on both

sides of the ledger as far as admirable and not so admirable. I could

just say on the positive side, I really learned a lot about what John

Coltrane was about and what the jazz experience was about, touring with

Archie and my playing got much stronger from working with him.

FJ: You have had a lengthy relationship with Joe Lovano.

KENNY WERNER: Well, I met Joe at Berklee. He was there for a year and

I was there for a couple of years. Now he says we met at Berklee, but

I don't really remember him there. I was playing a session in Cleveland,

which is his hometown. I was at a jam session and someone brought him

over. That's where I remember meeting him, but he said it was at Boston,

so I'll trust his memory better than mine because in the '70s I may have

wiped some memory banks.

FJ: I don't know what you are talking about (laughing).

KENNY WERNER: You know what they say about the '70s. If you remember them,

you weren't there (laughing). It was an interesting attraction because

I was everything he wasn't and he was everything I wasn't. Meaning, I

was into all types of commercial music. I was into music from '50s romantic

comedies. I was into music from TV shows. I could integrate it all in

one big cathartic concerto. He was a jazz player, son of a jazz player,

grew up listening to pure music. We were totally opposites, but I think

we were both rather fascinated with each other. Joe loved all the places

I could go that he would never think of and I loved how purely he could

play jazz and his voice in the music. Our careers went exactly that way

even though we were connected all the way through. He recorded on some

of my albums. In fact, this new album that is just coming out on BMG,

Beauty Secrets, he's on it again. For the first time in a long time, I

have him on one of my albums. I had been on a number of his albums. Of

course, his career really took off there. Even though we were connected

together one way or another, it was a very opposite experience. I was

bouncing from, I had so many sounds available to me, meaning, ways that

I could play, that I never really anchored in on what it was. Maybe it

is like a good left-hander in baseball. It takes a longer time for left-hand

pitchers to mature than right-hand pitchers. Maybe I am like that. I had

so much I could do, it was just as easy to do one thing over another.

But Joe simply always picked up the horn and played. Whenever he played,

he sounded exactly like him. It didn't what the context was. He really

taught me a lesson because in the '80s, if you can't sound like Michael

Brecker, what are you going to do? He just did what he did with all these

positive vibes and without a lot of thought about, again, the opposite

of what I was doing, which was thinking too much. The world came around

to his way of thinking. He hung in there and it was a great lesson for

me. Him and a few others taught me that. I would not have this criticism

of myself, if it is a criticism, of the last ten years or close to fifteen

years, I would say from the middle-'80s on I realized that God put me

on this earth to make the music that comes through my head and I should

really gear myself towards it. Joe was like that since the day I met him

and probably way before that. He comes from a pure lineage. It's like

if you are the son of a rabbi, you are not going to incrementally become

Jewish. He was like that. That's his religion. We always had something

for each other when we played. Today it is great. All he has to do is

start playing at the same time I start playing and perfect duet music

comes out. That's the way you grow with somebody. He's great.

FJ: Are you pleased with where you are at now?

KENNY WERNER: Yeah, I am. Finally, most of the time, the person I collaborate

with now other than my own music is Toots Thielemans. I been playing with

him quite a bit and although I occasionally sideman with him, meaning

playing in a quartet, but we have been doing much more duets together.

Duets is his gracious acceptance of me as an equal partner. We play and

we are billed that way. So that gig feels like my gig and so even the

one thing that I routinely do that is not "my own," it still feels like

my own because I can take the music anywhere I want. Between that and

I am doing much more trio work now, promoting the albums that I have been

doing on RCA.

FJ: Are you comfortable in the trio format?

KENNY WERNER: What happens is, the trio, if they are your sidemen, then

you can take it anywhere you want, almost like if you were playing solo.

And then if they are intuitive, they figure it out and the next thing

you know, all three of us are doing that. I think I have always been a

better leader than a sideman because my mind is always coming up with

different places that the music can go to. On a dime, we can be right

over here and really make a trip out of it. If you do that as a sideman,

you may actually unsettle the leader. The leader may not appreciate that.

I think I was fired more than one gig just for that reason.

FJ: You got a pink notice?

KENNY WERNER: You don't have to get fired. You don't get called back.

You hear the guy is playing somewhere and you weren't called for the gig.

It kind of equals that and I used to go through a lot of pain over it

and now, I think I understand it better because I understand myself better.

I'm just not a sideman. I guess this is what I have settled on now. If

the guy I am working for doesn't appreciate the fact that things come

to me and what I doing to it, trying to make the music better then I am

not in the right place. I want to make the music better. I don't want

to tune myself out so I can mail in the same performance every night.

If that unsettles the leader then obviously, I am playing with the wrong

leader. In Toots Thielemans' case, he loves the surprise and how it pushes

him and this thing has turned into a very risky and far out duet. It's

great. I'm writing music. I'm writing more orchestral music, which is

something I have been wanting to do for a long time. I am recording for

a real good company now. Yeah, I am happy where I am and I am making money

at it, which is really lucky because I have a daughter.

FJ: Let's touch on your first album for RCA Victor, Delicate Balance.

KENNY WERNER: Here's the thing, Fred. I was on Concord and before that,

my original company was Sunnyside. Sunnyside was a very pure little label.

The head guy was a really pure jazzman, who really appreciates his talent,

but in fact, like most small labels, spends nothing after the fact. He's

got a distributor. The distributor always tells him that everything is

OK, meanwhile, you don't actually see your CDs anywhere. I don't fault

them. They probably found that even when you spend money on promotion,

they still didn't do much better. The fact is, I started on Sunnyside

and record three albums for them, two of them with my trio, which I had

for fourteen years. That was a really unique trio. After fourteen years,

I broke that up. What is interesting about Delicate Balance, is that it

was my first attempt at doing a trio album with people other than Ratzo

Harris and Tom Rainey. So when I did this with Jack DeJohnette and Dave

Holland, as great as they are, even simplified versions really gave them

trouble. They had never played that stuff with me before. We got through

it. We got to a nice place with the music, but it was a real transition

record for me. I learned what it was like to play with great players,

but players who haven't played with you for fourteen years.

FJ: So there must have been quite a bit of rehearsing involved?

KENNY WERNER: No, everyone had busy schedules, so I simply booked four

days in the studio, so in my mind, the first two days could have been

rehearsals, if that's what they turned out to be. It turned out that by

the end of the third day, we had gotten the whole record. I was very happy

with it.

FJ: And you latest, Beauty Secrets.

KENNY WERNER: It starts as a trio, about three or four trio tunes and

then it spreads out like a butterfly. If you listen to it without the

usual references, I think you hear something that just develops and it

almost morphs into something else. That's very unusual for a jazz record,

so it is a little vulnerable to criticism if one likes a jazz record that

ends the way it begins. In fact, I am not about what is usual in jazz

and I have gotten to the point where that is OK. It provides a human experience.

After four trio tunes, Joe comes in with a duet. We do a duet and now

you hear a new tune and then I have a quintet that plays and then it moves

into an orchestral space and somewhere in there, it actually has one of

the most unique things on a jazz record, which is Betty Buckley singing

a duet and me playing piano, us doing a duet on "Send in the Clowns."

That's just a collection of just a lot of places that I'm at.

FJ: Ironically, listeners enjoy diversity, but critics really aren't keen

on this form of variety, aren't you concerned that this album may become

a critical lighting rod?

KENNY WERNER: You know, Fred, there is a certain expiration date as to

how much you will worry about anything about a record. Just like a guarantee

or something. It's past the expiration date. When I first finished the

record, I sort of worried about, what does everybody think of what I came

up with. But the longer it goes, I am not thinking about that record anymore.

I'm thinking about music that I am doing now and what I would like to

do next. I do think that that is a possibility and the dynamic in music,

in jazz and probably everything has always been that way. What can work

for people and might even make the music more attractive, doesn't work

for critics who think that they are the template. That's always the way

it is and so what you have to do is, bottom line, you have to decide what

it is as an artist that you are passionate about. Like anything else in

life, you have to align yourself with your passion. One thing is a little

painful, but I can't let it affect the other thing because the CD will

be forever. The criticism will fade into a blur of sound and noise anyway.

But I would be lying if I didn't say that it affected me. I would hope

that if I kept doing what I do, they would start to, you see, when Mingus

did something, they did not try to tell him what he should do. They got

to know who he was and then came to describe that, but somehow people

went from people who describe the scene to people who articulate and speak

for the scene. The artist that fit in that category aren't even worth

listening to. One time, I read to most elaborate, brilliant criticism,

more than a criticism, a review of a Philip Glass thing. The guy's writing

was brilliant, or it must have been because I did not frankly understand

a word of it. He had references to all these things throughout the history

of the world and places and movements and tribes. I did not know what

he was saying, but it looked like something terribly wonderful. I was

smiling to myself because I was realizing that he had all this lavish

language over something that barely exists. There is so little to his

music. Maybe that is what they liked, there is so little to his music

to talk about that they can just wax. The more the music has, the more

they should just simply describe it. That said, I made a decision after

this record too that every trio record that I do from now on will be live

record.

FJ: Why did to come to that dramatic decision?

KENNY WERNER: For a couple of reasons, a trio record is not such an ambient

sound that it needs to be done in such in antiseptic environment as a

studio. The way a trio interacts live is so much more affected by the

people sitting there drinking it in and soaking it up and we are bouncing

off of that.

FJ: How is the state of jazz here in the mainland?

KENNY WERNER: As far as work, America has gotten better. There's more

places where people are interested in jazz and it is not like all Europe

now. We go to Europe, but we also play around America. There is an amazing

pool of talent right here in New York City, unrivaled anywhere else in

the world. It so unbalanced as a matter of fact because if you added up

all the great players in the entire rest of the world, it would not equal

what is here. New York has become this absolute Mecca. Europe has crept

ahead on this, they are open to music that might have other influences.

Their jazz players play alternative music or new music with some Western

European classical elements. This for them is great. This brings the music

more home to who they are. So some of the most interesting experiments

go on over there, not more interesting than here, but there are more places

for it. They are not trying to hold to template or some media image, like

it is here. Now, I feel like it is opening up again here in America. Luckily,

the musicians are not waiting to find out what the media has to say about

the music. That would really he the horse chasing the cart. It is opening

up. You will find that people are attracted to new music in jazz and in

classical music. I had one guy tell me how in Canada one of the symphonies

was on its last leg and on a respirator. They were not getting enough

money from the government and of course, people weren't showing up to

hear the classics, but when they did their new music festivals with all

this wild and crazy stuff, it was packed. Sometimes it is the people that

get ahead of us. They don't realize they are ahead of us, but if you want

to bring people out of the woodwork, especially young people, you might

have to have something that exists in the time that they live in.

Fred Jung is Editor-In-Chief and washes the dishes and folds the laundry.

Comments? Email

him.