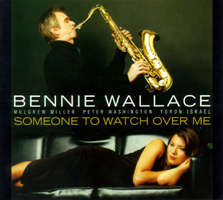

Courtesy

of Bennie Wallace

Enja Records

![]()

A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH BENNIE WALLACE

I have always been drawn to individuals. Muhal Richard Abrams, Andrew

Hill, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, John Zorn, Rahsaan

Roland Kirk, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Lester Bowie, Horace Tapscott,

are just a few names I can recall off the top of my head of persons who

have redefined the music, but in the process, defined a sound of their

very own. When I first saw Bennie Wallace live in a little café on the

outskirts of Los Angeles, I knew he would be a formidable force in the

music. His brand of tenor saxophone was progressive and yet, he was still

able to maintain the gentle swing of his Southern roots. He spoke with

me from his home in Connecticut about those roots, his forays into film

scoring, and his new release on the Enja label, Someone to Watch Over

Me. It is an intimate conversation with one of the most creative tenors

in the music today, all unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

BENNIE WALLACE: I started when I was a kid at about, I must have been

about the eighth grade. We had a new band teacher come to our school who

was a jazz musician and he introduced all of us kids down there in Tennessee

at that school to jazz, Count Basie, and to Sonny Rollins, Charlie Parker,

Miles Davis, all the really great music. He started up a jazz band in

the school and actually a lot of good musicians came out of that program.

I went from there to playing in after hours clubs around Chattanooga and

eventually make my way to New York and became a jazz musician.

FJ: Influences?

BENNIE WALLACE: Let's see. My first real influence was Sonny Rollins.

I heard Sonny Rollins when I was fourteen. That was my first artistic

experience, was hearing a solo that he played and really having it touch

me. I listened a lot in those days to "Lockjaw" Davis (Eddie), Stanley

Turrentine, and then I developed a little bit and started listening to

Charlie Parker, Stan Getz, and all those guys that played like Prez (Lester

Young), and Prez. Over the years, I remember listening to a radio program

in New York and they would play a lot of Ben Webster and Gene Ammons,

Coleman Hawkins and guys like that, oh, and a lot of Duke Ellington. So

I started listening to that music and I'm still listening to it and still

learning from it.

FJ: Do you recall your inaugural gig?

BENNIE WALLACE: Yes, absolutely. I had rented a practice studio because

I couldn't practice where I was staying. Monty Alexander heard me practicing

and needed a saxophone player and he hired me and got me in the union

and I played with him for half a summer with a really great band. I won't

forget that one.

FJ: Let's talk about the couple months with Monty Alexander.

BENNIE WALLACE: Monty was a fantastic leader, apart from the personal

part of it. He really took care of the musicians and treated musicians

with a lot of respect, but at the same time, he was a brilliant showman,

not in the flashy sense, but in the sense that he knew how to pace the

set and which tune to play at which time for the audience. It was a dance

job. He also knew when to call on me to play a solo. He had a brilliant

instinct of knowing how to shape a tune and shape a performance and shape

a set.

FJ: You have had a close collaborative association with Eddie Gomez for

as long as I can remember.

BENNIE WALLACE: Well, Eddie and I met, over twenty years ago. We were

both guest soloists with Larry Karush's group. So we played together and

really liked playing together and we played a trio concert with Eliot

Zigmund, who was the drummer in Bill Evan's group at the time. When I

got my first recording job, I asked Eddie to do it and one thing led to

another and we started. We've made a lot of records together and did a

lot of touring in Europe together and playing in New York. Eddie brings

a lot to the music. Eddie's phenomenal technique is well known and his

virtuoustic solo ability is well known. One thing that I noticed about

Eddie is a lot of the guys that tried to play like him used a lot of amplifier

with strings down low on the bass and don't really get a big acoustic

sound, but Eddie can really play the bass with a big sound and loud. He

and Dannie Richmond and I used to rehearse and he wouldn't even bring

his amplifier. You could hear him just fine. Eddie is also, definitely

the best reader of any bass player I ever worked with and also one of

the best readers of anybody on any instrument. He's got a really broad

range of experience and he can do a lot of things well that people wouldn't

expect like, for instance, on one of my Blue Note records, I wrote a tune

that was kind of a Cannonball Adderley style Charleston, where you'd want

a Sam Jones style of bass player on it. We were doing a recording session

of some other tunes and had a little extra time and we tried that and

Eddie just absolutely nailed it. He brings a lot to music, in addition

to the things that he's really known for.

FJ: And Ray Anderson?

BENNIE WALLACE: Ray and I met in 1972 at a jam session and I remember

walking into this place, I'll never forget it and I see this guy who looked

a little bit odd. And I thought he was a little bit odd in every respect,

the way he played, and just from the very first moment, he and I had a

natural hookup and way of hearing each other and playing together without

thinking about it and making it work. To this day, it's always worked.

It doesn't mean it will tomorrow, but there's just a real natural empathy

that he and I have with each other that was not just cultivated at all.

It was just there the first day that we ever played together.

FJ: And of course, John Scofield.

BENNIE WALLACE: John, I think the most remarkable thing about John is

his time. He's got a really great sense of time.

FJ: Let's touch on your self-titled quartet recording on Audio Quest featuring

Tommy Flanagan, Eddie Gomez, and Alvin Queen.

BENNIE WALLACE: Well, that is the second record that I've made with Tommy.

Our relationship goes back to 1981. I mean we haven't been playing together

with any kind of frequency, but he actually played with me on one of my

film scores and we've played one or two live performances in New York

together back in the '80s. To me, Tommy is one of the most outstanding

piano accompanists in the history of the music and an equally marvelous

soloist who really embodies the history of the music, but yet brings his

own personality to it. I've been really lucky to play with some really

great piano players, Jimmy Rowles, Tommy Flanagan, Mulgrew Miller, people

that really understand, not only how to make themselves sound wonderful,

but how to make a saxophonist sound wonderful. I just really love playing

with Tommy Flanagan. And I love going to hear him any time I get a chance.

FJ: Speaking of Mulgrew Miller, he appears on your latest Enja release,

Someone to Watch Over Me, an album of Gershwin melodies.

BENNIE WALLACE: Joe Harley, the producer, sent me a review of the album

that came last night and he said somebody said, "It was a dream band."

And I think that pretty much says it. I think Mulgrew Miller, I have to

say the same things about him that I said about Tommy. I can't think of

anybody that I love playing with more than Mulgrew Miller. Mulgrew and

I, we've played together with this quartet, quite often with Alvin Queen

on drums. I just love every aspect of his playing and I learn something

about music every time I play with him. Again, he's got an incredible

sense of time. He knows the music inside and out. I really believe that

he's the next great piano player. To me, the great piano players, the

great living piano players today are Tommy Flanagan and Hank Jones. I

think Mulgrew Miller is right up there. He's going to be the next great

piano player. I don't know if the business will recognize it or not. I

hope they do, but I don't mean that that is something he's going to do

in the future, he's got it right now.

FJ: What prompted you to record an album of Gershwin melodies?

BENNIE WALLACE: That actually came up by accident. I have to thank Ruth

Price for that at the Jazz Bakery in Los Angeles because Ruth invited

us out last May, a year ago last May in '98, and they were having a Gershwin

centennial program of the Saturday night the week that we were playing.

Marilee Bradford and David Raskin of the Film Music Society were kind

enough to ask us to play a set of Gershwin music and we weren't playing

any Gershwin music at the time and so each night we came to the gig a

little early and learned another Gershwin tune and kind of taught them

to each other and by Saturday night we had a set. And three weeks later,

we recorded them.

FJ: Sometimes it just comes together.

BENNIE WALLACE: It does, Fred. That was one of the really lucky accidents

because during that month there, I made a real study of the music when

I realized we were preparing for that week and the three weeks until we

recorded. I had played some of those tunes in the past or had learned

them and thought about them, but never really recorded or performed them.

It was really fun and a really wonderful musical experience for me, and

a really great learning experience. That was an absolute thrill to record.

Playing with those musicians was great. We were in a room just playing

without earphones, where we could really hear each other, which is something

that I do consistently with my albums. Everything was recorded live to

two-track with a great engineer, Joe Marciano.

FJ: It is serendipitous that you called me tonight, HBO has been rerunning

White Men Can't Jump, which I haven't seen in years. You composed the

music for the feature film.

BENNIE WALLACE: It's been a while since I've seen it. I haven't seen it

since the premiere.

FJ: Watching the movie again made me realize how significant the music

was to the film and how much the organ music drives the action sequences.

BENNIE WALLACE: Well, that's a whole other craft. Like I was talking about

Tommy and Mulgrew a minute ago, when I write music for a film, I really

think of guys like Tommy Flanagan as my mentor because instead of accompanying

a singer or a horn player, you're accompanying a picture and accompanying

the visuals and the sounds of the words or whatever is going on, on the

screen. It is an accompaniment process. It's interesting that you mentioned

that film, Fred, because now I am writing music for a Showtime series

called The Hoop Life. I'm working with a very talented producer. We're

doing a jazz score to a series film about professional basketball. I've

been doing it here in New York and using a bunch of really great jazz

musicians on the score. In fact, Eddie Gomez has been doing it quite a

bit, Mulgrew Miller, Peter Washington, Alvin Queen, Lewis Nash, Jon Hendricks,

who worked with me on White Men Can't Jump, came and did one. We're really

having a lot of fun on this one, because we're doing a lot of things that

are a lot more cutting edge than what we were doing on White Men Can't

Jump. This has really been a lot of fun.

FJ: What are the broadcast times for the series?

BENNIE WALLACE: It comes on, on Showtime on Sunday nights. I think it's

ten.

FJ: You have a very distinctive voice, one that is immediately recognizable.

BENNIE WALLACE: Thank you.

FJ: How vital is that, developing your own sound?

BENNIE WALLACE: Well, I think after good craftsmanship and basic musicality

and lyricism, that's absolutely the most important thing. That's one aspect

that is absolutely crucial if you are going to be an artist. It was Duke

Ellington that said, "I want to hear somebody that's the number one guy

at playing like himself, rather than the number two guys at playing like

somebody else." William Fulkner said, "Art is the expression of human

spirit." And you have to express your own human spirit and not try to

emulate somebody else.

FJ: And the future?

BENNIE WALLACE: There's a couple of projects that we are talking about

doing. I'm really interested in developing my ballad playing. Even if

I record original compositions, I've got some compositions that I have

written that have a relationship to the traditional song form. I really

plan to just keep building on the tradition. I really love playing ballads

and I've been thinking about some ballads that I want to record and we've

been playing some different ones in concert. The next album is something

that is very much on my mind. I haven't quite settled on what it's going

to be. I think I should record something this spring. I like to coordinate

a recording with a series of performances. I find it is good to play the

music, play with the musicians, play a few concerts, and then go away

from it for a couple of weeks, kind of like what we did on the Gershwin

thing, then come back with a fresh mind and record it.

FJ: At the conclusion of your career, what would you like your legacy

to be?

BENNIE WALLACE: I guess, I want to be remembered for having my own voice

and for playing the way that I play and doing it well. I think beyond

that, the most important thing is I'd like to be a great ballad player.

When you're real young, you want to be the next Coltrane or the next Sonny

Rollins, and all that and then when you have been in it a while, or when

I have been in it a while, I hear Coleman Hawkins play one of those ballads,

or Johnny Hodges or Ben Webster, I want to be able to do those and record

those and tough people's hearts like those guys did. I think I'm kind

of winding around to articulating my thoughts and I think that is really

it, to be able to touch people's hearts with the music.

Fred Jung is Editor-In-Chief and believes in mermaids. Comments? Email

him.