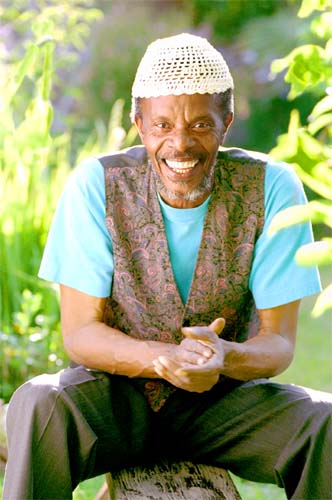

Courtesy of Horace Tapscott

HatHUT

![]()

Arabesque Recordings

![]()

A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH HORACE TAPSCOTT

The following is the first Fireside Chat.

Please forgive me if I seem a bit wet behind the ears. It is fitting that

Horace Tapscott started the show. He was after all, the reason why I became

interested in improvised music (John Coltrane as well, but I was too young

to do a one on one with J.C.). I love Tapscott, his music, his dynamic

approach to the piano, the way in which he electrified audiences, his

dedication to the black community in Los Angeles (my hometown), and the

gentle nature of the man. It still pains me to think that he never received

the recognition for his tremendous work while he was alive, but in his

death, people can't memorialize and write about him enough. Where were

you when the man was with us? You're coming out of the woodwork now, but

where were you five, ten years ago? I cannot even begin to say how much

Tapscott means to me. I could write a book. I would only hope that you,

too, had an opportunity to be touched by this monster of a player and

a gentle giant at heart. And if you were, perhaps, this conversation will

bring about fond memories, as it does for me, each and every time I read

it. It is my honor to present unto you, Horace Tapscott, unedited and

in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Was the piano your original instrument?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: Yes, piano.

FJ: How did you discover the piano?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: My mother. She was a pianist. She was in an old jazz

band.

FJ: Was she a big influence on you?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: Oh, yeah. She played in two bands. She played tuba in

one band. She also played another instrument I'm not aware of. But she

did play the piano. She had a piano in the house all the time.

FJ: You were in the Air Force. What was that experience like for you?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: That was another kind of experience. It was a good learning

vehicle as well as what's gonna happen in society when you step out of

there. I had a lot of enlightenment in the service. Racism hit at its

peak when I was in the service. My dealing with racism had its peak in

the United States Air Force. At that very moment, the armed forces were

desegregated so everybody was in a strange mood. The white guys had never

been with the black guys and vice versa. There was a lot of stuff going

on. However, I was in the band, you know.

FJ: When so many musicians have left for the New York scene, what kept

you in Los Angeles all these years?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: Well, you see I did go to New York for about two and

a half years. I was there in Lionel Hampton's band and lived there for

a while. However, at the time I was living there, I learned some more

about racism and the fact that the music itself, music by black composers

and performers, was just getting lost in the dust, you dig? They were

getting turned around and I didn't like that kind of stuff and wanted

to do something to help change that. I felt like if I went to New York

again or had I stayed in New York, I would have missed raising some of

my children where they should be raised and at the same time, I felt that

this was one music and we were missing the point. The music itself was

getting lost. The credit part of the music was getting smothered and that,

to me, was very disturbing. So I figured if I stayed here at home and

tried from scratch, how to work it, say what I feel, what I believe, and

try to put it in some kind of emotion and action, and gather some other

people with those same kind of ideas about preserving their race, and

culture, and music, and things of that nature. And what was the best way

for me to do that, I thought, was to be in the community where people

that are not aware about the music itself can be themselves a part of

the music. I thought that might be the better way to get across. I felt

that it was either this or that. Going to New York, where I could have

been doing certain things much more than I am, but I couldn't say it's

much more quality as I am here, at home, watching different things happen

in front of my eyes after all those years.

FJ: You mentioned the community. You do so much on behalf of the Los Angeles

community. What has kept your enthusiasm fired up to keep giving back

to the community?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: You see, I was raised in a segregated society, which

means I was raised differently from what young people are raised today,

which meant that everybody trusted everyone. Everybody helped each other,

believed in each other, inspired one another, chastised one another when

they were wrong, and it did not have to be your particular family. Sure,

I could have gone back. I could have done a lot of things. I turned down

an offer to a Boston white college. They were offering me that kind of

college gig. I don't know how it got to them, but at any rate, it was

the fact that it was something I believed in, the fact that I was raised

in it, around the music and around the people that were used to being

around each other and wanted to help one another. I want to transfer that

to where I live. I still want to be able to walk the streets of my community

without looking back. And I feel that all the music we're hearing now

had to come from somewhere and it did come from the community. All the

music started right there, slated in the underground at that time.

FJ: In reference to your community involvement, you have played numerous

festivals in Los Angeles that are free to the public. The Watts Jazz Festival

is a good example. Do you prefer to play to the masses in that type of

forum or do you prefer a more intimate setting like the Jazz Bakery?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: Well, after all this time now, I can take them either

or. I'm very used to doing festivals cause it brings the crowd and that's

what brings about these kind of gigs (referring to his stint at the Jazz

Bakery). But, the fact was that you had a chance to showcase different

things from the community, which the other parts of the community might

not be aware of, which is very important. It doesn't have any time setting

on it. It's just a thing you do while you're here. And when you're gone,

somebody else may come along but it has been dealt with and now people

are aware of the things that are going on right around them, up the street

from them.

FJ: You were recently in New York for the Lincoln Center performance.

What was that like?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: That was very interesting. All of us from here went there

and you saw some guys who used to be here, there. It is very nice to get

a chance to show what is happening on both coasts because it's all one

music.

FJ: How do you feel about the future of jazz in Los Angeles?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: I think labels and things just separate from what is

really happening. What I want is when your grandchildren open up a book

in the library, I want them to be able to read, for sure, this music was

indigenous to this country and done by slaves. Take it from there I'm

thinking about the wholeness, so to speak, that comes out of African-American

composers - the future of the wholeness, what happens to it. So many friends

that I know and grew up with have gotten ousted from things that they

have written that have become very popular all over the world and they

didn't get credit for it because they were black composers. I feel the

same way as I felt before, regardless of the new century because there

should be a change to look forward to and there's still so much work to

do. And the work needs to be done by people who believe in it, not by

someone who wants the publicity because it is not going to be a picnic

and a lot of things happen that can discourage you.

FJ: Are record companies manufacturing stars?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: That's true, they are manufacturing stars and it's like

everything else they're manufacturing that used to be natural and the

same results are going to happen. Pretty soon, you'll have robot bands.

One thing about music, they can copy it all they want, but there is no

replacement for it. You can't handle the music. You don't throw it around

like you do the atom bomb because the music is going to be there. I know

that. European music, Asian music, music is going to be there. What we

are talking about here is recognition of the music, that simple thing.

Not asking for any, well, I guess we are asking for certain kinds of money,

but more then that, just asking for recognition. I am not surprised. Big

companies, and I respect that, they came here to do business and they

don't care abut your music and they let you know that, so we're going

to manufacture some music. OK, fine, but that can only go so far. It can't

go as far as they want it to. Elevator music and all that kind of things

will only last however long it's going to last. It will never replace

the live musician.

FJ: Do you have plans to record with your Pan-African People's Arkestra?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: I am. I am very much in plan. We're rehearsing now.

FJ: Describe your current project.

HORACE TAPSCOTT: It did not take very long to record because all the music

on there is old. All the things I recorded were things that should have

been recorded. I did not get to record it, so that's what I'm doing now.

So I've got quite a bit to go before I get into some other things, but

that project is still there to preserve and to get the music out.

FJ: Aiee! The Phantom, your last album, was a quintet album. What made

you choose to do a trio recording this time around?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: I don't want to record too much with and horns unless

they are from back here, more or less, and that is one of the main reasons.

FJ: And the future?

HORACE TAPSCOTT: The very same things. Walking that walk. Seeing and enjoying

it. There are so many things to keep you there, like live family. That

is what I look forward to, still doing those same things, only on a much

more grander level, of course. That's about it, Fred.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and loves Tuna Helper. Comments?

Email

Fred.