Courtesy of Sony Simmons

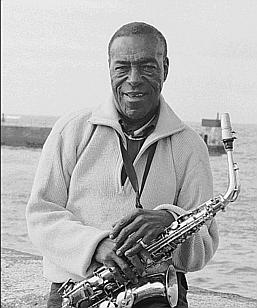

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH SONNY SIMMONS

I love Sonny Simmons. Like Charles Gayle, perhaps, it is because Simmons

has witnessed adversity in the most challenging of forms. But also, like

Gayle, Simmons can play the saxophone. I wish more labels would have the

balls to record Simmons, but alas, nobody has balls these days. That is

why I am starting the Roadshow label. Send money now (we accept American

Express) and together, we may be able to document a musician worth his

weight in gold. The standard of alto playing, Mr. Sonny Simmons, unedited

and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

SONNY SIMMONS: Well, what happened here is that my daddy was a preacher

and he was first vocalist in the church. He was the pastor of the church,

Reverend J. S. Simmons. My mother, she was first female vocalist in the

church choir. We were all musical. I'm just about six years old, bright

eyed, curly haired, little black kid that loved to go to church on Sundays

and hear the music. I think I was about six years of age or six and a

half. But I do remember quite vividly my upbringing in music. My dad also,

not only being a great vocalist, he was a hell of a trap drummer. Back

in those days, they called them traps. They didn't call them drums. That's

how far back that music began with me in the backwoods of Louisiana. So

I grew up with that type of, I think I was born with it. I can't say that

I learned it as I progressed into the future of one's life. But I do think

I was born with it and it came from a long lineage of ancient fathers

and mothers and our ancestry because my daddy really had it and he was

one hell of a preacher. He's one of the greatest preachers I ever heard

preach in a church, in a Baptist church, black folks in the ghetto and

all over America. He was the greatest I heard and I've heard a lot of

preachers. But anyway, Fred, that was my background of growing up in music

because at that time, I would attend church with my dad. I would look

forward to it on Sundays. He went to the store somewhere and he bought

me an old squeeze box accordion. Black and red was the color. I never

will forget it. He just gave it to me and told me, "Look here boy.

You can learn how to play this." It was a musical instrument. He

squeezed it a little bit and sounds came out and it hypnotized me and

so I fell in love with it right away. So I looked forward to every Sunday

to bring my little squeeze box accordion. That was the only instrument

I had at the time as a kid. And I would play it in church with him every

Sunday to squeeze and press keys. It was an old, beautiful accordion,

but it was old. It played and I dug the sounds that it transmitted. That

was my earliest instrument that I could recall as a child growing up in

Louisiana, near the Gulf of Mexico with the tribal music and voodoo that

was going on at that time. The music and my blues heritage, my uncles,

a lot of them played guitar. They was all blues masters, but they never

went anywhere with it. It was just on the island with the family. My dad

was the high priest of voodoo music and when he would do the voodoo ritual,

all the peoples in the island, they would be dressed in white and they

would come to this great, big festival of voodooism, but it was all for

good. It wasn't for sticking the pin in the doll and that kind of shit.

FJ: That is Hollywood exploiting a stereotype.

SONNY SIMMONS: Yeah, that's right, Fred. It wasn't for that. It was for

good. My father would go through the voodoo ritual and he would utter

some words that I never heard since. It was for the good of peoples being

healed who were sick. It was for the good of the land that it might have

a big bumper crop. It wasn't for evil. So I don't know nothing about what

Hollywood was doing there, promoting that propaganda on black folks.

FJ: I am trying to close my eyes and imagine you as a squeeze box accordion

player.

SONNY SIMMONS: (Laughing) You can't fit that it. Well, as the years progressed

into the future of one's life, I mean, I am six years old, six and a half

in church when this was going on. That was the only thing that my dad

could get me. He didn't get me a whistle or a horn to blow or an old,

beat up trumpet. He just went and got the squeeze box accordion and so

I appreciated that. As I grew from six and a half to ten or twelve, I

didn't have no more interest in the squeeze box. I began to evolve to

a higher level, so I would listen to a lot of music, classical music.

In fact, when I was growing up as a kid, I thought those people, those

voices I heard in the old radios, the old, wooden box radios, I thought

it was little people inside of them. That's how innocent I was because

I would hear these voices of people that I see everyday and see them talk

and I'm thinking as a kid that these are little people inside. But anyway,

my thing was all music. I put on a music station and I would sit there

all through the days sometimes when my mother asked me to do chores. I

be listening to classical music. I be listening to blues. I be listening

to Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw and all those cats back in those days

and Duke Ellington and Count Basie and those are my main boys because

there was a big hit on the market in the early Forties during the War

days called "One O'Clock Jump." Boy, the brothers and sisters

wore the jukebox out putting nickels and dimes and I was right there with

them doing the same thing as a little kid growing up around the music.

As years progressed, my dad moved to California from Louisiana. He was

a traveling preacher, a minister. He found a home for us in Oakland, California,

the home of the Black Panthers, the revolutionaries in Oakland, California.

As the years went, I think I can remember very clearly, vividly about

fourteen years old, I would go see all these peoples like Duke and Basie

or Cab Calloway and Lena Horne and Louis Jordan. Man, I am telling you,

Fred, I've seen all these cats alive when I was fourteen and you had to

only pay fifty cents back then. You dig? So I am growing up around all

this music and then, as the years passed and I was going into my teens

years, I heard Charlie Parker, I was seventeen years old at the Oakland

Auditorium and man, it changed my life.

FJ: How did Bird change your life?

SONNY SIMMONS: I had never heard no music like that before, all the years

I was growing up, into my teens. To see this beautiful black man stand

up there and fill the whole auditorium with all these beautiful sounds

that I had never heard before. I fell in love with the music and also

the man who was producing it. I told my parents. I said, "I want

a saxophone." So I started out on saxophone, but really my true instrument

is cor

anglais. It is an alto oboe. It belongs to the oboe family. They call

it the English horn sometimes. I prefer to call it the cor anglais. It

is a double reed instrument. It is only played in symphony orchestras.

So I was very attracted to that instrument when I was about ten because

I used to listen to a lot of classical music and I loved the sound of

cor anglais. It is so eastern and it is so ancient. I've been playing

it for years. I grew up with this out of my teens. I've recorded many

albums with the cor anglais. And I have some new ones coming out soon

that I have now. I've been playing the cor anglais for years. They call

it the English horn. It's an alto oboe. It is very rare. But anyway, I

am still playing it. I am playing it today very frequently. In fact, when

I get back to Europe soon in the next two or three weeks, I am going to

start a string quartet featuring the cor anglais. I'm going into that

kind of music when I leave America. I'm going back to Europe to find a

place to hideaway to write for a string quartet and the cor anglais. I

want to change my style of music, maybe I can really make a living at

this instead of what I'm doing now. That's my plan, Fred. However, the

music started after Charlie Parker, where I was indoctrinated by Bird's

music and just tied it in with all these great saxophonists. They had

Lester Young and they had Illinois Jacquet. They had Diz and they had

Bud Powell and they had Ray Brown. I've seen all these cats when I was

a kid, so I come up under their influence. They had a great influence

upon me, jazz music by Afro-American people. There was a few white boys

that I dug and white ladies that could sing. I dug them too. Doris Day,

I dug her. She was a movie lady, but she had a nice voice. You see, Fred,

I dig talent. I don't care who produces it. I even dug Artie Shaw and

that was way back in the Forties and he's a white boy. And I dug a little

Benny Goodman. He didn't kill me too much.

FJ: I hear some Bird in your playing. Frankly, if Bird was around today,

I always figured he would be playing like Sonny Simmons.

SONNY SIMMONS: Obviously, you have heard some of my work. I've always

tried to be in that concept of Bird's playing, but not just sound like

him.

FJ: In those days, everyone and their mother tried to sound like Bird.

SONNY SIMMONS: That's true. They did. I practiced everyday and I did sound

like Bird in the early days, very much so. But after growing into your

own voice, you loose some of that. You just don't deal with that, but

Bird is always with me. I can pick up my horn right now and play some

Charlie Parker because I was indoctrinated by him years ago. My recording

venue in my life has been so poorly handled so I didn't get a chance to

do a lot of these things in the early years like Seventies and Eighties,

like I should have. Now, we're in 2000, but I'm still with Bird, the new

Bird, so I am into that right now.

FJ: You referred to your recording output and the lack there of.

SONNY SIMMONS: That's true, Fred. That is what happened.

FJ: Why have record companies shied away from documenting your work?

SONNY SIMMONS: I have no idea, Fred. I really can't give an accurate answer

to that because I was under contract in California with a beautiful recording

company located in Los Angeles, Hollywood, Los Angeles, named Contemporary

Records. Lester Koenig, he took an interest in my music because he recorded

all the brothers that could play that were great artists.

FJ: He certainly did, putting it in the wind and recording Ornette (Something

Else!!!, Tomorrow is the Question!).

SONNY SIMMONS: Yeah, he did. He started off and took a chance with Ornette.

He was a great producer. My last album that I did with Contemporary, I

think I did three or four of them with that label and the last one was

a double LP, which was fashionable at that time. It was called Burning

Spirits, double album at that time. He was supposed to follow up with

another album with Elvin Jones, I mean, Coltrane's rhythm section, he

wanted to record me with them. And a month later, this cat dies of a heart

attack in his Beverly Hills mansion, in his home. He dies of a heart attack.

So my dreams went down the drain after that because I was only recording

because I was hooked up with, in the Seventies, was Contemporary Records

and Lester Koenig. God bless his soul. But he died and my whole thing

went down the drain. After they released Burning Spirits, they blacklisted

me because I spoke out about politics and about all the musicians like

Albert Ayler and Eric Dolphy and God knows who else and they thought I

was starting some kind of political thing.

FJ: Why did you speak out about Albert Ayler?

SONNY SIMMONS: Albert was a hell of a musician. He was real and he wasn't

just another saxophone player. To me, as an individual saxophone player

myself, and a person, and a fan, Albert was an innovator. He was not just

another saxophone player. He was great. He was an innovator. And he started

the new music and the avant-garde as they call it today. Albert Ayler,

he's original. He was the first cat I heard to play out like that and

then Coltrane heard him in the early Sixties and he fell in love with

him. He knew that he had something that no one else had and then he died

so suddenly. And I spoke about that in my liner notes when I done this

last recording for Contemporary Records called Burning Spirits and they

blacklisted me for twenty-five years after that. I couldn't get no dates

no more. Didn't nobody want to deal with me. I couldn't even work in clubs

anymore. I'm telling you, Fred, I went through all the Seventies with

no work. I went through the Eighties, until about 1980, I got to work

in San Francisco because I left. My family life broke up. I had raised

two kids and worked day jobs for years.

FJ: In my home, Ayler is an icon, but history has failed to recognize

his role.

SONNY SIMMONS: Because the media and the radio stations doesn't push that

kind of music and then a lot of so called jazz stations, they don't push

it either. They push commercial jazz. He had made it to the top of what

he was supposed to be about and he became a very heavy star with ABC/Paramount,

Impulse!, same company that Coltrane was with before he passed away. Bob

Theile was recording him at that time. It is just really traumatic about

how he passed away suddenly at the heap of his recognition in the East

River in New York City.

FJ: Ayler's death and the circumstances surrounding it have become urban

legend. Do you know what happened to Albert Ayler?

SONNY SIMMONS: No, I have no idea, but I have my suspicions.

FJ: And they are?

SONNY SIMMONS: I wouldn't want to say that at this time since I am already

a target for controversy and politics.

FJ: Fuck 'em.

SONNY SIMMONS: (Laughing) That's the way I feel too. OK, at that time,

I had a little studio on 6th, right here on the East Side, Lower East

Side, New York City at that time, back in the Sixties. All the cats used

to come by my studio and we would practice. I would be practicing all

the time anyway. And at that time, Woodstock was booming and I had a house

up in Woodstock at that time, so I could go from New York to there. Albert's

brother, Donnie Ayler (Donald Ayler, trumpeter), used to come by my studio

a lot. Now, Albert, he was working a lot at that time. He was in Europe

and so he got wind of what his brother was doing and so he used to come

over and bring his horn to my studio on 6th on the Lower East Side at

that time. And we would all practice together. Now, along with that, I

found out that Albert was dealing with some unsavory white boys uptown

because he was living up in Harlem at that time, him and his brother,

Donnie. They didn't want to deal with Donnie in the recording industry.

They just wanted Albert. You dig it? They didn't want to keep them together.

So Donnie used to come and tell me a lot of stories about when him and

Albert were together in the apartment. They were living together. They

were brothers. And these white boys knock on the door and he would have

to be excused from their presence. This is what Donnie used to tell me

and I thought that was very strange and unsavory and cloak and dagger

shit, something is wrong here. It really tore his brother up emotionally.

He couldn't understand that. Then I saw Albert times after that, during

that period before he died mysterious or killed mysteriously or whatever

way you want to look at it. He was shot and he had just signed a new contract

with ABC. They extended his six month contract and he was looking good,

Fred. Albert looked great. He was dressed in fashion quality clothing.

He had hundred dollar bills in his pocket and he was feeling good and

the brother deserved it and I was happy for him. So we celebrated. He

took us out to dinner, bought some drinks and we got drunk and all that

shit. After that, Albert went to Europe again. I moved from New York,

at that time, to California, back to Oakland. I was working on the road.

One day, I was driving my van on the freeway in California, at that time,

and the jazz station announced that Albert Ayler just had passed away

mysterious. His body was dragged out from the East River and the East

River is not too far from where I was living in the Lower East Side. That

messed me up. I almost got into an accident driving on the freeway at

the time when the news came over KJAZ in Oakland. It messed me up. I pulled

to the side and got out of the car. Man, I was pissed. I was tore up.

I went psycho. Yeah, I went psycho on the freeway. Motherfuckers, people

were driving by and they didn't know what's wrong with this crazy nigger

on the freeway, just going berserk. I was kicking the car. I was pounding

the motherfucking hood, just the front of the van. And shit, Fred, I just

went berserk there for about, maybe, two or three minutes. Then I got

back in the car and drove off. That was the end of my association with

Albert at that time. That's all I can tell you about the brother, Fred.

I know he was a beautiful brother. He was one hell of a musician, saxophonist

and he took it one step beyond and he was truly an innovator. He wasn't

just a saxophone player. I love Albert's music. I love Albert, period,

because we had a brief association at that time, but it was very valid.

FJ: I recall my father telling me in my youth that the company you keep

defines the man you are. By that standard, you are a man among men because

you also collaborated with Eric Dolphy as well.

SONNY SIMMONS: Oh, ah-la-lo-la-lay! I hear you brother man. Eric, Fred,

I am telling you man, the way me and Eric met, this Jew boy in New York

at that time, he had a loft on 2nd Avenue and 4th Street. Clifford Jordan

was the leader of that trip. He found this Jew boy, who was interested

in recording jazz musicians at that time. So Clifford came and got me

and took me over to the loft and the cat's name was Fred and he loved

the music. He cared about musicians. They could stay at his place if they

had no place else to go and he'd give them money to buy what they need.

He was that kind of guy. But anyway, we were rehearsing there one day.

It was Don Cherry, Grachan Monchur, the trombonist, Charles Moffett, Ornette's

drummer at that time, and Clifford Jordan, myself and also Prince Lasha

was present and that was it. We were rehearsing on some new material for

Fred and in walks Eric Dolphy. I couldn't believe it. I was sitting there

with my alto and my cor anglais and my horn almost fell down onto the

floor (laughing). Dolphy comes in and I wrote a new composition called

"Music Matador," and we were working on it and Eric said he

loved it because it reminded him of California, back home, where he was

born and raised, down in Los Angeles because a lot of Mexican people live

in the area and there's a lot of Mexican music going on that he grew up

with. The melody reminded him of his early upbringing and so he fell in

love with the melody. He asked me that he was going to take me into the

recording studio with this melody. We all were going to play. He hired

Clifford Jordan and dead in walks Woody Shaw. This kid just came into

town back then. The kid was eighteen years old. Yeah, man, in walked Woody

Shaw. I don't know how he found the date and the studio. J.C. Moses was

the drummer and Richard Davis was the bass with another bass player. I

forget this brother's name. I can't recall this brother's name, but he

was important on the date (Eddie Kahn). It was one hell of a recording

date with Eric as the leader. Our association grew from that and then

we done a second date, which came up from that one date called Iron Man

and I'm on that date also with Eric and then we just developed a beautiful

association. Each time he would come over to the loft, we would practice.

And then, he also would take lessons. I couldn't believe it. Here is a

cat that I am in awe about and his ability to play all three of these

appliances, these instruments, rather, equally (alto saxophone, bass clarinet,

and flute), not one for a showpiece or gimmick. Eric played all three

of those instruments equally and he was astounding. And so he said, "I'm

taking lessons. Do you want to take lessons," from a great teacher

in New York at that time. His name was Garvin Bushell. He had done some

recording with Coltrane on the cor anglais. It is a tune that John wrote

called "India." That was Garvin Bushell. Eric would take lessons

from this cat and he took me over there and I took some lessons too a

few times at a hundred dollars an hour that he was charging way back in

the Sixties. I learned a lot from Eric and I learned a lot from his teacher

that he was taking lessons from. That astounded me, but anyway, we developed

a real beautiful, close brother relationship. Eric was a beautiful guy.

He didn't do nothing. He was always clean cut and beautiful and he loved

the brothers who were trying to struggle to play. Coltrane was the same

way at the time because all these cats was alive then. And then, shortly

after we had grown and developed a beautiful friendship, he goes to Europe

with Mingus' band and he remains in Europe. Mingus and them come back.

They came back and left Eric there. Eric said that he was going to stay

and I don't blame him. I would stay too because he was a tremendous musician.

He passed away in 1964.

FJ: When did you get the word?

SONNY SIMMONS: I got word of it, I think it was about a week later, because

it happened in Germany. Dannie Richmond came over to my studio and told

me what really happened. I didn't like what happened, what Dannie Richmond

told me because he was with Mingus' band at that time in Germany. The

brothers that were there believe the printed matter, the newspaper media

and all that shit.

FJ: You crossed paths with Mingus.

SONNY SIMMONS: Yeah, I played with Mingus' band, back during the time

when Charlie McPherson was done and Lonnie Hillyer was the trumpet player

and I was living in San Francisco at that time when Mingus would come

through the Jazz Workshop.

FJ: Was he as much of a hard on as rumor has it?

SONNY SIMMONS: He was a motherfucker, but he was a good guy. He was just

hardcore when it came to certain things. He was very sensitive to certain

things and he would get violent.

FJ: What would set him off?

SONNY SIMMONS: Disrespect, not listening if he said something about music,

or not playing it correct and if you keep stumbling over it like you don't

care, he would get pissed off. Normally, anyone would do that at certain

times. Sometimes, he would get abnormal with it. He was that way because

we had a brief association in New York before he died. He used to come

to my studio. They just had released a new book, this book that he had

written called Bravo. You will find it if they still have it in print.

It is a hell of a book that Mingus wrote about his life. He celebrated

that and that was my last hook up with Mingus. However, when we met in

San Francisco, he wanted me to work with his band. At that time, he had

Rahsaan Roland Kirk working with him. So I was there when it was going

on and he asked me to work with him and take Rahsaan's place and I said,

"No." That's when we fell out. I was a young cat then. I think

I was about twenty-seven, twenty-eight years old. I was playing very well,

alto bebop. Rahsaan was a killer and I loved Rahsaan. At the time, we

called him Roland Kirk. We called him Roland. The brother's blind and

he's playing three horns simultaneously. I said, "No, the brother's

blind and I can't take this brother's job." He's great and I love

him because I buy his records too. And Mingus got pissed off with me.

He said, "Nobody ever turned down to work a job with me." I

said, "Man, it is not that. It is just that I don't want to take

Roland's job." It was as simple as that. He's blind and he's playing

like a motherfucker. If he was jiving, I would have took the job. But

here is a guy and he's an innovator. He is astronomical. So I just told

Mingus that I couldn't take the job.

FJ: There is an unwritten code, you don't piss in another man's pool.

SONNY SIMMONS: No, I don't do that. I don't practice that. I was raised

by Christian peoples in a manner of speaking. It didn't have much effect

on me, but I do believe in God and there is certain things that I don't

do. I've always kept that honor with myself and I feel good about it.

FJ: Historians have a perception that you "dropped out of the scene."

Did you step away willingly or were you forced out?

SONNY SIMMONS: I was forced out, Fred. I had to work on the streets of

San Francisco for fifteen years, on the streets for fifteen, long, grueling

years. I was homeless for fifteen years, working on the streets. I was

a strung out junkie. The shit fucked me up, stuff I had never done in

my life is use drugs. I didn't start using no drugs until I was forty-two

years old, Fred. That was during the Seventies when they blacklisted me

and Lester Koenig of Contemporary Records died. And I just got very manic

depressant, Fred. I went into a whole lot of shit that I had no business

dealing with, but I done it. That wasn't the tragedy. The tragedy was

for fifteen years I was in San Francisco working on the streets for nickels

and dimes, being insulted, spit up on, objects thrown at me and all kinds

of shit, police call on me like I was a dog. I done went through that

shit. It is just crazy. I hadn't disappeared. I hadn't left the music

scene. It was just that these motherfuckers wouldn't hire me. In order

to take care of myself, I had to result to that, so I used my talents

to over. I don't like what I have to do on the streets, but when you're

homeless, when Reagan came into office during the Eighties, all these

black people were on the streets and I was right there with them. I was

just a black man. They didn't give a fuck about my reputation or about

my occupation, none of that shit. And I'm just playing saxophone on the

street and that's all they would look at, like it wasn't shit. So I survived

them fifteen years taking care of myself on the streets during that time.

I kept my sanity together because I was playing music all the time.

FJ: Music was your salvation.

SONNY SIMMONS: Yeah, it was. Had I been doing anything other than that,

I think I would have went under a long time ago.

FJ: Lesser men would have laid down under such anguish.

SONNY SIMMONS: That's right. It was because the love for the music, just

plain and simply, the love of the music. I just love the music and I love

playing my instruments and performing. That's what it was. That's the

bottom and top line, the love for the music. The talent that God gave

me, I've always honored and respected until this very hour that we're

speaking about it with love. Hardship was both astronomical and traumatic,

but just because of the love, I kept coming back. I wouldn't throw in

the towel because of the love and all the cats that I knew, that I came

up with, that helped me and inspired me along the way like those giant

like Coltrane and Dolphy and Mingus and Monk. I also had an association

with Monk. I've got some real, true life dramas to tell you about musicians

that I hung out with. All those brothers died for this art form, the fine

art of jazz on the battlefield in this polluted system with corrupt and

fucked up and racist and fucked up. The whole trip, the machine destroys

people, Fred. They died for that and so I still got to stand up.

FJ: You have been fighting the good fight, honoring musicians who have

sacrificed their mortality for the music's advancement, how do you feel

icons like Coltrane, Ayler, Mingus, and Dolphy would feel about the music

today?

SONNY SIMMONS: I think they would be very pissed off about it because

I'm pissed off about it because of how corrupt it became and the machinists

don't feed it, but only to certain masses and they screen the other shit

and hold it back. They keep it on the commercial beat and the commercial

tone, where it can get to the average Joe and that's not what's happening,

Fred. The music should be exposed to kids. The whole conglomerate of what

the system is, in America and in the art form and in the fine art of jazz,

should be exposed to kids and all the way up. It should be on the radios,

but it isn't. It is on certain radio stations and then they only pump

certain stuff. They don't pump the real thing all the time. They dabble

and dib.

FJ: Your homecoming took the music by storm as you released two classics,

Ancient Ritual and American Jungle, for Quincy Jones' label, Qwest. Why

did you not sign an extension with the label?

SONNY SIMMONS: Well, they wanted to pick up the option on me, but they

wanted me to come back with an agreement for the option for less money,

so I refused to do it. The first CD made a big headway for me in the world,

not just in the US, in whole entire world. So I wanted more money for

the next recording, to pick up the option to continue to work with Qwest/Warner

Bros. After the guys come back at me like that with less money. I mean,

the money was so much less that I might as well have gone on the streets

and played for nickels and dimes to make that kind of money. They wanted

me to resign with them for three thousand dollars, Fred. Three thousand

dollars, man, are you kidding? That's what they said. That ain't nothing,

Fred. That wouldn't even make a recording. So I told them motherfuckers,

"You all can have that shit. Give it to somebody else that is desperate

and starving and younger and they might be able to deal with that, but

I can't deal with that shit." So I just told them that and they didn't

get in contact with me and I didn't care.

FJ: Fuck 'em.

SONNY SIMMONS: That's exactly the way I feel about it.

FJ: You also recorded two blowing sessions for the CIMP label, Transcendence

and Judgment Day.

SONNY SIMMONS: The recordings, the music was fine, but the recording is

zilch. The guy don't know how to record, Fred. I done put this on an expensive

machine because I like to hear my stuff surround, stereo, Dolby, all the

way around the room and you put this on and you have to turn the volume

all the way up and you just can barely hear it. So I was very disturbed

behind that because I didn't know the recording was that bad. On the first

one, it was OK, but on the second one, Judgment Day, which was very important

to my career and to me as a person, the musician, to present the tenor

saxophone in the context that Albert and Coltrane left here and the cat

done a terrible recording job on it. So I don't have too much respect

for CIMP recording technicians. He's (Bob Rusch) been trying to get me,

but I always refuse. I can't deal with that anymore. I have to be exclusive

with some refined people who really understand the fine art of jazz music

and who will recognize the fact that here is a brother who is still alive,

in this day and age, who walked with the giants, slept with them and ate

with them, played music and recorded with them. So they don't even want

to acknowledge that, so I don't really give a damn. I'm going on back

to Europe and start me a string quartet with cor anglais. I'm going to

change my whole musical idea. I'm not going to even play jazz anymore.

FJ: Why turn your back on jazz?

SONNY SIMMONS: I'm tired of the lifestyle that goes with it and the way,

Fred, I am sixty-seven years old and I ain't got shit except blacklisted

and still talked about and disrespected and refuse to give me jobs like

you're supposed to and recorded. I can't even get a recording date.

FJ: Do people fear Sonny Simmons?

SONNY SIMMONS: Yeah, I think so.

FJ: Why are they afraid?

SONNY SIMMONS: A whole lot of different psychological things of their

own. It is like some Sigmund Freud psychodrama with the people outside

of me because I don't have no problem, Fred, if I am dealing with a refined

person of high perception and sensitivity and hip to the arts and to human

nature, we can communicate fine, but I guess whatever their psychological

problem is with themselves, they see that through their eyes and put that

on other people as well.

FJ: There is too much fucking drama in this music.

SONNY SIMMONS: There sure is, Fred. It is getting psycho sick. I ain't

even trippin' on it. I just want to find me a place to hideaway in Europe

and I'll never be heard of again. They think they heard of that fifteen

years in San Francisco drama. They won't hear from me no more. I can't

find nobody to work with me.

FJ: Whoa. Let's not get crazy now. You keep fighting the good fight baby.

If your voice went silent once more, we would all be the lesser for it.

SONNY SIMMONS: I hear you, Fred. I am going back to Europe to stay. I

don't plan to come back, but if I do come back, it would have to be for

a lot of money and something exclusive. Otherwise, I'm going to stay in

Europe.

FJ: I had better start fundraising like a motherfucker.

SONNY SIMMONS: I hear you, Fred.

Fred

Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and the best player in the WNBA.

Email him.