Courtesy

of Archie Shepp

Delmark

Records

Black

Saint

Jazz

Magnet

A FIRESIDE CHAT WITH ARCHIE SHEPP

I have read Archie Shepp described as "radical," "controversial," or "disturbing." Why? What is so "disturbing" about speaking your mind about subjects beyond the music? And why should writers even be focusing on Shepp's political views anyway? He is first and foremost an artist and as one, we should judge him by his discography, not his politics. I have always been challenged by the tenor, who was immortalized in the 1965 Newport Jazz Festival concert recording, New Thing at Newport. I was honored that Shepp took time away from his busy schedule to sit down with the Roadshow the day after he returned from Europe. I bring it to our babies, as always, unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

ARCHIE SHEPP: Well, my father, he was a banjo player and he liked to sing. There was music all around me. My community was rich with music and from that point of view, my cup runith over. It was inspiration for me. That was the one thing that poor black people had was music and a musical environment. It was a very rich musical environment and a very original one.

FJ: Why did you put down the banjo?

ARCHIE SHEPP: Well, you know, Fred, it wasn't hip. I guess when I got to Philly, I was born in Florida, in the South, where things are much more bucolic and rural, but as I moved to the North, the guys were playing pianos and saxophones and basses and I began to see other things and hear other things. It is your personality as well. I guess I wanted to some degree to be out front. Since then, I have found out that basically, I make as much money as a saxophone player as I would have being in the back (laughing). When we moved to Philadelphia, I started formally on piano. My parents were poor, but music lessons were not really very expensive because, here again, Philadelphia is so rich, like many of the cities, Detroit and Chicago, there were always black people and instructors who had graduated with degrees and Ph.D.s and couldn't find a job in music and symphony orchestras because of the racism. So they ended up teaching kids in the park in their neighborhood for a dollar a lesson, two dollars a lesson. That is how I studied.

FJ: It is difficult for the current generation to relate to the struggles of the Civil Rights Movement.

ARCHIE SHEPP: The question that I would ask, Fred, is why aren't they familiar with it because I don't think things have changed profoundly much. You might say that there is a black middle class that has become less and less observant of its own community and its responsibility to that community, but that doesn't mean that the problems have disappeared. I see more and more homeless people on the streets. I see my people struggling harder than ever. I think the facade has changed. Cities are being gentrified. Fortunately, thank God, I am living in a nice home, but I know a lot of my people don't enjoy those opportunities.

FJ: Whereas the racism during the Civil Rights Movement was blatant, the underlying prejudices in this country now are more subtle.

ARCHIE SHEPP: Oh, yeah, you might say that. But in Los Angeles, they had Watts there in the Sixties and Rodney King, why wouldn't black people and people of color be really hypersensitive, oversensitive? I could say what it was for me. As you say, Fred, it was more in our face, but not so much even that. Look at what happened in Brooklyn. The guy was shot by the police, this Haitian guy (Amadou Diallo) raised his hands up to say that he was cool and he was shot forty times. There are atrocious, really terrible things going on in the world today that unfortunately, young people are blind to these things. I think you have a generation of young black people who are totally incognizant of the struggle that went on to put them where they are. For example, I saw an interview with Wynton Marsalis in New Orleans with all his buddies and homies and he was saying, "Growing up for me was like apple pie." That is typical of young kids today. He is not a young kid, but that is typical of young men of his generation. Things were provided for them that people paid a lot of dues for in the Sixties to create. I've been watching some of the old films of Dr. Martin Luther King, especially for the tone of his speeches and the language, which I find more and more inspiring. I can go to it as a resource for my own soul, to answer things for myself. I think of the immensity and the enormity of that struggle and the depth of that struggle and what it did for young people today. I am amazed, especially by black people, of their ignorance of their own time, of their own recent time, their total insensitivity to the dues that were paid by the people to create the changes that we see today.

FJ: Influences?

ARCHIE SHEPP: When I first started out, I guess I listened to a lot of blues and my pop always had Duke on the record player, Count Basie's "Royal Garden Blues." We had quite a collection, even guys like Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman. My dad played all that stuff on the radio. Then he played all the folksongs. I really had a good background. The music of that time, which was coming out of the swing era, was my initial exposure. Around the early Fifties, a friend of my father's rented a room out in my father's house and he introduced me to Sonny Stitt and Lester Young and that is how I first got into this music. I had the good fortune to meet Lee Morgan when I was about sixteen and he was really quite a big help to me. He was really a prodigy. When I met him, he only had been playing about a year and a half. He was already playing the first chair in the All Philadelphia High School Orchestra. He transposed and sight-read excellently. He had a very good knowledge of harmony, chord changes, which he himself probably learned from his mentors. By the time I met him, he was already a very advanced musician. He helped me in many ways. I started out taking piano lessons until I was ten years old. On Saturdays, I used to go to Lee's house and he would practice all day, especially Saturdays. He had this book, this trumpet book, which they call the Bible for trumpet players and by the time he was fifteen, he had played that book back to front every Saturday. That is what he used to do. He needed a piano player to play simple changes for him while he went through his "jazz reparatory." I would comp for him and that is how I learned how to comp on the piano, really just playing chords straight up for him in the background while he played.

FJ: That seems like it was a proactive time, does it concern you that the time we are living in now is so passive in comparison?

ARCHIE SHEPP: That too of course, but I think that there is something behind all that. All that had to happen anyway with the evolution of African-Americans society as blacks become more and more integrated into the white middle class experience. They begin to shed all their former community reference and values. I also tell my classes that black people are becoming whiter and white people are becoming blacker. Most of the kids in my class who are really hip are white. It is a fact. If I got a class of sixty students let's say and I asked how many of them have heard of Sidney Bechet and maybe five people would raise their hands and invariably four out of five, if not five out of five are white because I know no black kids know who Sidney Bechet is. It is not in their background. He knows who Mozart is. He knows who Beethoven is. That is why he is in school in university, to find out about who somebody else is and not about who he is or she is.

FJ: Let's touch on your collaborations with Cecil Taylor.

ARCHIE SHEPP: Yeah, I joined his band in 1960. Here again, Fred, the times were quite different. This music was, in a sense, right in tune with the whole revolution and the speeches of Martin Luther King and the Black Panthers, the black Muslims, we were right in tune with all of that. We weren't making any money, but I mean, we played at lofts for five dollars a night. Dennis Charles and Don Cherry and whatever money we made, we split up and would give it to our political organizations.

FJ: That kind of loyal dedication is so sadly missing these days.

ARCHIE SHEPP: Well, because we were in struggle at that time. We would give money to our political organizations to press leaflets. We would go up to Harlem. We would support whatever was going on at the time, Urban League, the more radical Black Panthers, whatever. I played concerts, gigs, spoke on the streets. I was engaged. You don't find that these days, but why would you? I think the world has been made more comfortable. It is the world of Oprah Winfreys today. She is the model for black women, in the sense that she is a billionaire. I don't think she does much. She is typical. There is nothing against Ms. Winfrey. She is a very talented and a beautiful woman, but I don't think she is very effective even though she is rich. That is typical of our people today with young billionaires and all these musicians and Michael Jordan and Shaq. What is the name of that singer? She is quite beautiful. She has had some problems recently.

FJ: Whitney Houston.

ARCHIE SHEPP: Whitney, yeah. I think they form a class of people today that for young black people, they are set up by the establishment to be seen as models, but in fact, these are really hollow men and hollow women. They are people without any clue of their own political history or historical knowledge of where they come from, even their understanding of their own culture and what they produce and its meaning to other things that are produced within their own culture and so called jazz music. They don't see any relationships and they don't make any relationships. The people who should really be controlling jazz today should be Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson and these people. They should be putting their money into that kind of production. Of course, jazz doesn't make any money, but they could use it as a tax write off. White folks do. The problem with the Negro is that I think is that basically we still haven't recovered from our slave mentality. Look at all this music made by black people. It is a thirteen billion dollar industry and there is not a single jazz club of any stature owned by a black man or woman in the United States. If you know one, tell me.

FJ: Damn, and I wanted to be original.

ARCHIE SHEPP: If you did know one, that would be doing pretty good. If you could count them on your fingers, that would be doing all right. Not a single trombone is made by a black man. Not a saxophone is manufactured by a black man. We have no companies to make musical instruments. Why not? Italians are known for eating spaghetti. They also make it.

FJ: Let's talk about your work with the late John Coltrane. You appear on his seminal Ascension recording.

ARCHIE SHEPP: I can say for me, that he is a man that has profoundly affected me and my life. When I have musical problems, I often go to Trane and he helps me. I couldn't say enough about the man.

FJ: Sounds like you miss him.

ARCHIE SHEPP: Of course. I can go to him as a source of resource. He was always there and he is still there. I do.

FJ: You had a long association with the Impulse! label and in recent years the label has been re-releasing a lot of your titles. Do you get royalties from those reissues?

ARCHIE SHEPP: Well, some things I get paid for, some things I don't. In fact, the longer I stayed with the company. I began to learn how to protect my own work. So I eventually formed my own publishing company. So those things that I recorded as we went on, from Attica Blues, from the time of Mama Too Tight, at that point, I began to put more things into my own publishing company and so on. So to that degree, I do receive some receipts. I wasn't hip enough at that time to sign artist royalty contracts, which is what makes the difference. It means that when they re-release these things, you get money from the releases as well. Now, I get money from the publishing end or the writer's end, but no artist royalties, which could now really account for something.

FJ: The adjective that has been most closely associated with your music has been avant-garde. Does the term have merit?

ARCHIE SHEPP: Well, I have never accepted that term. I have always seen it as divisive, commercial. It is like jazz, funk, disco. There are so many ways to describe a black man and the black people's music. When we talk about the white folk's music, we think romantic, baroque, classical. Those names mean something. We think music. But with the negro, we think bebop, blues, blah-blah-blah, blah-blah-blah. I wonder if people like Whitney and these people have ever thought about giving their own music a name themselves. Something that white people didn't give to it. Like what Monk said. Monk said, back there in the Fifties, someone asked him why create bebop and he said, "Well, we were trying to make a new music that the white boys couldn't cop."

FJ: So name your own music.

ARCHIE SHEPP: Music. Why not? What is so hard about the word music? People know what it means. You say jazz and nobody knows what that means. What does jazz mean?

FJ: I don't have a dictionary in front of me.

ARCHIE SHEPP: I know. It is the music that was created in 1917, a music for brass and woodwind instruments meant to imitate the blues and the spirituals that have previously been sung and played on banjos and guitars. So jazz is an instrumental music. For example, Ella Fitzgerald is a jazz singer, but why? Because she sings like an instrument. Billie Holiday is a jazz singer. But she is often compared with Lester Young. The thing about jazz is that it was the time of negros. Before that there was slavery and black people couldn't afford trombones and saxophones and clarinets and those instruments. After 1917, some people say that about the end of the Spanish American War, 1890s or something like that, the United States Marine Band began to put huge number of instruments on pawn in pawn shops around the country, especially around the mid-Southwest, where a lot of these early negro brass bands developed, Tennessee, St. Louis, Louisiana, those areas. So that is jazz. There is nothing mysterious about it. It was when negros began to play brass and woodwinds and the reed instruments.

FJ: I am first and foremost a fan.

ARCHIE SHEPP: Well, thank you very much, Fred. I'm trying to do better.

FJ: It has always been a source of angst for me that you have not documented your music more prolifically in recent years.

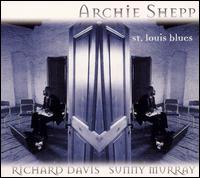

ARCHIE SHEPP: I made a lot of records, Fred. It is just that you haven't heard them. It is just that the establishment isn't really so anxious to expose what I have done. There are some things I have done that I think were creditable and some things that were quite good. So I can't say that my work has been so even over the years, but I certainly have been recording. The thing I did with Kahil (Conversations on Delmark). I've done some things on Japanese labels and Something to Live For (Timeless). I've done a few things. You can find it. I am also at www.archieshepp.com.

FJ: I will put out the good word.

ARCHIE SHEPP: Well, you've got to. We are out here fighting the good fight trying to make it better, Fred.

Fred Jung

is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and a Judge at the Miss Universe Pageant.

Comments? Email

Fred.