A FIRESIDE

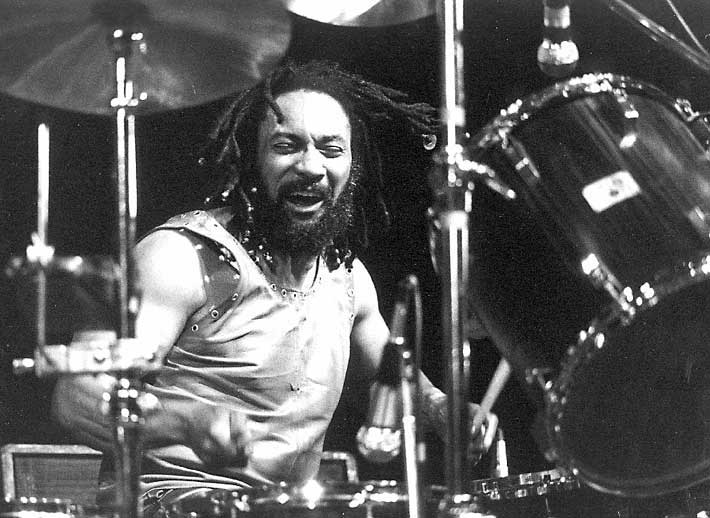

CHAT WITH RONALD SHANNON JACKSON

I am not certain about many things outside of politics, having worked

for various Congressman through my short lifetime. But I am certain that

Ronald Shannon Jackson should be all over the place, playing, recording,

and doing what it is that Shannon does to his heart's content. There would

be justice in the world then, but that is a pipe dream and the reality

is that if it were not for devoted producers like Jim Eigo and Knit (for

reissuing the stuff), Shannon would be but a fond memory and a new generation

of eager listeners would not get an opportunity to hear the music of Shannon

(outside of the DIW imports). Shannon attributes his lack of time in today's

sun to his opinion that he is being blackballed by the industry. That

may not be too far out when you consider that he has skills a plenty and

should be all over the place. We could and do do much, much worse. I am

honored to present, Mr. Ronald Shannon Jackson, in all his splendor, unedited

and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: I been knowing that I was going to play drums

since I was four years old. I saw some in a church when I was passing

through. My father was the local jukebox operator here. From five years

old, I used to go with him every Saturday and I would wipe the jukeboxes

off, count the change, and put the 45s on. He had a monopoly on the jukebox

business here, so in order to run that business, he opened a record store

here at Fort Worth, Texas. I was always around music. My father's sister

was King Curtis, who was the musical director for Aretha Franklin, my

father's sister was his mother. I grew up in a town that is a very musical

town, producing the likes of Ornette Coleman, whose mother actually passed

a block away from where I am at now, Julius Hemphill, Dewey Redman. My

first music teacher was John Carter, the clarinetist, who had graduated

from Lincoln University in Missouri at nineteen years of age. My mother

played piano and organ in the church. I was around music all the time

and I was always strumming the strings on the bottom of the piano because

we had an upright Steinway in my home. That is the environment I grew

up in. At twelve and thirteen, you could actually go around and see Jimmy

Reed because he used to play here all the time. All the blues players

used to stop through and I knew most of their music through the records

we had to put on.

FJ: With your mother playing the piano and organ, conventional wisdom

would be to play a keyboard instrument.

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: Well, they made me take piano lessons when I asked

for drums when I was about five. They made me take piano lessons up until

I was nine. I received my first drum set because that was the only way

that they could get me to finish high school. It was such a money making

town that I didn't really have to go to school and so, of course, I got

out seven times the last year. So rather than have me come back, they

put me a grade up to go into the army and my mother agreed that if I would

do that then she would buy me a drum set. So my graduation present was

my first drum set.

FJ: You have made the most of that investment.

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: (Laughing) Yeah, right.

FJ: People go where the money is. You were where the money was. Why did

you leave?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: I left here to go to college at Lincoln University.

When I left here, I had a full scholarship to Westlake College of Jazz,

out there on the outskirts of Los Angeles, which is defunct at this time.

I didn't go there. I went to Lincoln University because Julius Hemphill,

who already attended school there, explained to me that it was located

in the middle of Missouri, between Kansas City and St. Louis, so if we

missed someone and didn't have the money to go the weekend the person

was at St. Louis, we could catch them the next weekend in Kansas City.

It worked out to my advantage very much so. So I went to Lincoln University

and my first roommate was this fellow who was studying agriculture and

he wanted to get up early, so I asked this other kid to move in my room

and he switched rooms and this other kid who moved into my room was named

John Hicks.

FJ: The piano player?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: Yes, he was my roommate for that year. Of course,

I had quite a bit of money and so I went out and bought a stereo and all

the latest jazz records and so my room was the hangout for all the musicians,

which included Oliver Lake, Oliver Nelson, who had just come back to school

that year, Julius Hemphill, Lester Bowie, we were all there at the same

time. We used to play music all night long. We used to always get stoned

and just play music all night. Every time I left home, I always made money

playing drums. Right near the school was the Missouri Mining and Engineering

School, which is where they opened up the first McDonalds and so I used

to buy bags of hamburgers and malts and lots of fries. Every night I would

come home from work and we would all eat because we were all spending

our money staying stoned and playing music. After that, I went to Connecticut

to the University of Bridgeport and from there, I got a full scholarship

to NYU through Kenny Dorham. So that is how I moved to New York City from

Connecticut.

FJ: What is the key to playing drums?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: The bass drum is the key to playing drums. I know

how to play the bass drum. Hicks was the musical director with Art Blakey

and they had come back from Japan and they were playing at Slugs, and

so I drove down to see him and as soon as he saw me, the first thing he

said was, "Man, you have got to move here. You can work." And I was shocked

because I was always afraid of New York. People in this area go to California,

not to New York.

FJ: And drummers you respect?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: Art Blakey played the drums. Tony Williams played

the drums. Philly Joe Jones played the drums. Papa Jo Jones played the

drums. Chick Webb played the drums. Ed Blackwell played the drums. Basically,

Fred, I play the bass drum. I play the drums. And all the people who play

drums, all the people who I admired play the drums and all the great leaders

allowed the drummer to play the drums, including Albert Ayler.

FJ: Let's touch on your association with Albert Ayler.

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: Ornette Coleman was having a squabble with ESP

Records at the time and he didn't want Charles Moffett to make any records

with ESP. This fella, Charles Tyler had been brought to town to make a

record at ESP. Charles Moffett asked me if I wanted to make the record

date and I agreed. We played the song with one take and after the record

date, I cried because I was so torn about my feelings about what had happened.

In the meantime, when I came back to pack up my drums, this fellow who

had been standing around in the studio, who had a beard with a gray spot

in it, it looked kind of unique, and he asked me if I would play with

his group. I said, "Yeah." I asked John Hicks who the fella was that had

just asked me to play with him and he said it was Albert Ayler. Of course,

I had never heard of him. So I started working with Albert Ayler.

FJ: How was Albert Ayler unique?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: He taught me to play the drums the way I play

the drums at home when no one else was around, to play the drums the way

I enjoyed playing the drums. That is what made him unique. He was not

afraid to allow me to drums.

FJ: What are other leaders afraid of?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: The problem you have, Fred, and it has even got

extremely worse now, it is an ego problem mainly. The drums are an instrument

of excitement in the first place. In Africa, they are used to talk long

distance. So it is easier for a drummer to be the center of attention

in any group, but what is not understood is that it is necessary for the

drummer to be open in order to make a group work. This is what Miles and

Coltrane understood and also what Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington,

all these people understood that. Chick Webb is the only black musician

who has ever received a doctorate from Yale University in 1939. If the

drums is working and the bandleader don't have an ego, then they can make

music happen. We have come to a time period where the leader has to be

the saxophone player or the guitar player and the drummer has to be squashed

down in the background, but that is not happening. That is one of the

reasons why you don't have anything new happening. The other reason is

that there is a concerted effort to take the music back to what Charlie

Parker and them was playing, which Charlie Parker, if he was living, wouldn't

be playing right now. What you are really asking, Fred, is what made that

music work the way it worked? One thing is that most music critics, I

was going to wait to put this in a book, but from the middle of America,

not on the East Coast and not on the West Coast, but coming straight out,

down from Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland and that area, were a lot of Masonic

temples and since it was the era of segregation, you had the white Masonic

lodge and the black Masonic lodge. And the black Masonic lodge always

had these musical instruments and these marching bands. Here you have

a situation in the black community where you have these instruments in

the schools, but you also have these Masonic temples, where they had all

the major dances. That music we played and the kids were taught at these

Masonic temples was the kind of music that Albert was coming out from.

So when people were saying that Albert's music sounds like march music,

it wasn't that as much as it was an open 4/4 music with the improvisation

and the sound that you would hear in the Masonic temples, which wasn't

heard in the general population. That has never been spoken about because

most of the critics, who write about jazz, don't know the key words to

open, like in an interview, a person can only tell you what you trigger

them to say and since most people who do interviews are so arrogant in

the first place, most of the time, I read things where people don't even

call me. All they have to do is pick up the phone and call me and I would

have told them the right dates and things. It is no probl That has never

been spoken about because most of the critics, who write about jazz, don't

know the key words to open, like in an interview, a person can only tell

you what you trigger them to say and since most people who do interviews

are so arrogant in the first place, most of the time, I read things where

people don't even call me. All they have to do is pick up the phone and

call me and I would have told them the right dates and things. It is no

problem. You want it out there correctly. But people can be so arrogant

and they have so much power, they just write what they want to write.

As you know, Fred, whatever people see first is what they believe. You

put a rebuttal and that is three months or four months later and a lot

of people don't even see that.

FJ: And your work with Cecil Taylor?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: I worked with Cecil Taylor exactly six months.

And out of that six months, six records were recorded. What it was was

three of the records were just live radio broadcasts. One night, I was

out wandering around. I had a dollar in my pocket and I was hungry because

those were starving days and I went down into the Village Vanguard and

I went down into the kitchen, which is the dressing room and Cecil was

playing there at that time. We started talking and he asked me what I

do and I told him that I played drums. He asked me if I could play and

I told him that what I play, I played better than anyone else because

I was already playing this mantra. I gave him my number and he called

me. A couple of days later, he asked me to talk a cab with my drums over

to his loft. We started playing and Cecil had about four or five telephones

in this loft he had and I noticed that he went around and took all the

phones off the hook and we just played and played for a few hours, just

totally improvised and that is how I got that gig.

FJ: Let's touch on your association with Ornette Coleman.

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: From Mingus (Charles Mingus), I got a gig playing

with Betty Carter, through Joe Chambers, who was working at the Five Spot

with Freddie Hubbard. Betty didn't have a drummer and she got mad at Joe

and Joe turned her onto me. And then, I have never told anybody in early

interviews, but I got strung out and I was out of the scene for a long

time. When the spirit came back to me, I started back playing. I have

to stop and put an interlude here because I stopped playing when they

put up Sputnik in Texas.

FJ: The Russian satellite.

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: I was driving home from my father's store and

I was driving across this bridge, smoking a joint and when they announced

that they had put up Sputnik, I realized that I didn't know what made

airplanes fly and so I came home and told my mother I wanted to go back

to school and that is why I went back to school. So I played with Betty

Carter and after Betty Carter, I was out of it for a long time and then

when I came back on the scene, I played with Ray Bryant. I don't even

remember if we had a week off because we would go out on the chitlin circuit.

In those days, you would play a week in each town. We stopped on one trip

and stopped and made a song called "Ode to Billy Joe," which was popular

at that time on 45. On the B-side of the 45, we recorded "Ramblin'," which

was Ornette Coleman's song, which is how I really got to know Ornette

Coleman. We were born and raised in Texas, but he is ten years older,

so I didn't really know him. I saw him one time when he came back, but

we were over in the bushes looking at him and Don Cherry when they were

going into the joint. They were big stars and we were country boys down

here. I met him one day crossing the street of 2nd Avenue and I told him

that we had just recorded this song and he said that he would like a copy

and so I brought him a copy and that started a relationship with him.

Then I faded off the scene and then when I came back on the scene, I had

kicked my problem and I was working downtown on the East Side. I met Ornette

Coleman when I had taken a girl to this restaurant and he said he was

looking for a drummer and I gave him my number. The next day, he called

me and that is how I got the gig with him. He asked me to make a commitment

with him for four years because his son, Denardo, was studying business

at city college and he was going into his first year. When I met Ornette

that Sunday, he had already tried out seventeen drummers. The problem

he was having was that he had this nineteen-year-old kid from Philadelphia

playing electric bass. He was wanting to go electric. I had been practicing

Buddhism and my attitude had changed a hell of a lot. I was trying to

make everything positive and not dwell in the negative. What happened

with the other drummers, because he told me, was after they got through

playing, they all enjoyed playing with Ornette, but they would tell him

that he needed to get an upright bass player and so he would never call

them back. And when I went around there, he left us in the loft, Bern

Nix, Jamaaladeen, and myself. He left us for about four hours and he came

back and asked Jamaaladeen and Bern how it was and they said it was beautiful

and so that is how I got the gig.

FJ: How were you able to relate to Jamaaladeen Tacuma and Bern Nix, when

seventeen other drummers could not?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: It didn't matter what instrument the person was

playing, it was what their spirit was doing. That is the way it has always

been with me. To give you an example, Fred, when I was with Ray Bryant

and we were on the highway coming back to New York, after about a six

or eight week chitlin circuit thing, on the Hudson Expressway, coming

back to New York, when they announced that Coltrane had died. Something

seemed like it just left, right at this little hole at the top of your

head, this little indention. It seemed like something just hit me and

I knew I wasn't going to play no more and I didn't for a long time. The

same with when they put up Sputnik. The spirit just left and after I quit

doing the heroin thing, actually, I was still doing it. It came back on

me and I started humming all the time and whenever I start humming all

the time, I know it is time to play. Just like now, I am sitting out here.

Theoretically, I am supposed to be blackballed. I play when it is time

for me to play. Whether it is for three thousand dollars or for charity,

it is up to me. It is more with me about the spirit.

FJ: Society these days is very hard on a man of spirit and principles.

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: Fred, business and companies cannot create music.

They can create disasters like they got going on now because you don't

have anything fresh or new coming out.

FJ: Why do you feel as though you have been blackballed?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: I can play music. I know and this is a talent

and a responsibility that I have been given. I knew this and understood

it. People who do the things like I do, we have a different kind of sensibility.

When I was a kid, I always had lots of problems with my ears. They took

me in to see the doctor every three months to get my ears cleaned out.

If I got into a car and the windows were down, I would have the worst

headaches. Once I grew out of that, I had this ability to hear things.

I can sit in a place and hear things. That allowed me to listen. There

is a big difference between listening and hearing. In order to write music,

you have to be listening. That is what I do. I listen to the surroundings

that I am in and I listen to people. When I meet people with good spirits,

I write songs. I write melodies, which is what Ornette told me. Ornette

told me to go buy a flute because I wasn't playing drum solos. I was playing

melodic solos on the drums. My spirit has always been one to play the

melody, the same as the first time I heard Elvin Jones. I was very arrogant

in those days, but to me, it was like here was somebody who sounded like

he was trying to play like me. I was still in Texas. I had never left

Texas then (laughing). People come together in music because of music,

not because of some business people. I wish there was a situation where

Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich and other great white drummers because then

I wouldn't be persecuted so much. I should be playing all the time. All

you have to do, Fred, is think like this. If I was white, what would I

have? I would have everything at my feet, but because I play drums and

when I was growing up, the drummer was looked at like a linemen in football.

He is nothing but a dummy with meat on him and muscles. I play drums.

I write all my melodies and through Buddhism, I became a leader of a band

because I never had no intentions of being a leader of a band. I just

wanted to be one of the greatest drummers living and to make people happy.

I used to write poems about that in school. They don't want me out there

playing. My CDs are being taken out of the stores, not because it wasn't

selling, because if you look on the internet, you are going to find about

eight whole pages of people selling my CDs. If you go to the record store,

my CD sells more than everybody else's.

FJ: Why have you not recorded more?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: They have studios that are sitting up there with

nobody using them. They would rather for them to be barren and nobody

is playing than to open them up to get music. I don't understand the craziness

that is going on. I'm a person born a baby boomer. Music is vital to people's

well being. If you know history and you can see what they did in Nazi

Germany with music, why don't they allow music to happen here. There is

a concerted effort to make everything the way certain people want it.

Why not let it happen the way it used to happen? All the bands that I

have been with, people used to ask me how I got this band together. I

didn't go out seeking to put a band together. I was sitting here the other

day when on TV, they announced the making of a band on TV. How you going

to make a band on TV? It is easier to have a survival show than to make

a band. A band comes together out of the spirit. We all should honor the

spirit. People deal with religion and not with their spirit. If they dealt

with the spirit, we would have a much different country. They just past

a law here in Texas, giving people permission to carry their guns to the

football games and to church. Now, what is the need to carry a gun to

a church?

FJ: How high is the crime rate in Texas that one needs to carry a loaded

firearm to a football game?

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: Or anywhere? I'm saying that these studios are

just sitting there. Why not let people go in there and make music? If

you go to Spain, in the lower part of Spain, these people get together

every night. They smoke hash and drink Johnnie Walker black and they play

some of the most beautiful music that you would ever want to hear. I played

guitar and I haven't ever tried to play guitar in my life. People play

music all the time and it was through my travels that I see that three-fourths

of the world doesn't teach music because it is not necessary to teach

music, anymore than it was necessary for me to be taught music. I taught

myself how to write music. In this society, because of business, because

of greed and capitalism, you have to go to school four years to learn

something you already know. I was reading this article about Phish the

other day, who was on the cover of Down Beat last month, and the drummer

was saying something that I had been saying a long time ago when I used

to do interviews, the first thing I tell people when they come into my

band is to go back when you asked your mother to buy you an instrument

and when you first got your instrument and didn't know the technicalities

of the instrument, you could play your ass off. It was only that you started

learning changes and other stuff, that the problems came in. The rest

of the world don't know nothing about 4/4, 6/8, or ¾, or the keys or what

else. We in this western world, because England couldn't hear B and most

black people hear in B flat, English people hear C, so we have got middle

C as a criteria. If it is a note that I can't hear in my head, I immediately

know that that is C. Once you travel the world, you see that they improvise

and they harmonize together. Now, why can't we do that here?

FJ: Decode Yourself has yet to be released in CD format.

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON: Not only that, Fred, but they squashed it. They

never put it out. It would have made me again, the popularity that they

don't want a drummer, especially a black drummer to have. The people that

they have designated to talk about drums and about drummers, here you

have people that weigh damn near two hundred and fifty, three hundred

pounds talking about they're drummers and these are the people that they

choose to write articles on drummers. They are already jealous because

how are you going to play drums and your ankles are bigger than your thighs.

Even though you might have talent, having talent is one thing. If you

want to do what the spirit requires you to do, you have to do twice the

amount of work and I'm not a person that works eight hours or twelve hours

or sixteen hours. This is a twenty-four hour job because you hear melodies

at the time they come, not when you want them to come. A person like myself

is not allowed to work and I have been blackballed throughout the system.

People have told me, people who have access to that information from the

computer.

FJ: Yet another reason for me to bury my head in the sand.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and a member of the cast of

the next Real World. Comments? Email

Fred.