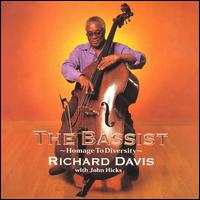

Courtesy of Richard Davis

Palmetto

A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH RICHARD DAVIS

Richard

Davis holds a place in my CD player because of his contributions to Eric

Dolphy's Out to Lunch and Andrew Hill's Point of Departure. Other than

that, the bassist's music holds little interest to me. Interviewing Davis

on the other hand was a pain in the ass (read it and the word brutal comes

to mind). One word answers to seventeen word questions is about as clever

as a knock knock joke. But Davis did play on Out to Lunch and he did play

on Point of Departure and In 'n Out, so if there is a pass, Dick just

got one. It ain't much, but it is unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

RICHARD

DAVIS: Well, the fact is, it just fascinated me because I liked to hear

it. I was raised in a very musical background in my neighborhood, the

Southside of Chicago. I have many recordings from New Orleans, Louis Armstrong,

some old stuff, old music.

FJ: Why bass?

RICHARD

DAVIS: I was fascinated by its shape, sound, position in the band, kind

of low key. I think I was a shy kid and I didn't want to be out front.

My cousin told me to play it. He wanted me to play it because I liked

it so much. The first bass I played was a Gibson. I played that as long

as I was in school. I didn't have a bass when I first started and so I

started off on a school bass in the summer time. My first bass really

was a broomstick. I imagined that it was a bass and I would play it. But

then I bought a Kay bass at Christmas time that my mother bought for me.

FJ:

When did this become your life's work?

RICHARD

DAVIS: I guess from the very first day that I picked it up. That's my

general makeup. If I got out and try to do something, that's it.

FJ:

When did you make the move to New York?

RICHARD

DAVIS: Nineteen fifty-four. The scene was everything I imagined, all these

great musicians walking down the street and playing at the clubs. There

was always a job and that made it easy to be working. But all the great

bass players, the man just died in December. Do you know who that is,

a great bass player?

FJ: Milt Hinton.

RICHARD

DAVIS: Yes, Milton Hinton. Everybody knows about him. Milt Hinton is a

legend, a legend who lived 91 years. A few thousand people came to his

service last Sunday. I was one of them in New York at the Riverside Chapel.

Every bass player and people all over the world were there. You should

have been there. I'm just kidding with you.

FJ: I gather Milt was an influence.

RICHARD

DAVIS: Milt Hinton was an influence on every musician that ever picked

up any instrument, not only because of his music, but just his life. His

influence on me is to be the best I can in my field and to look out for

other bass players coming behind me like he did for me and many others.

He was a very giving person, never asking for anything in return, except

that we give to others. I first met Milt in 1954, when I first came to

New York. I went to his house. He invited me warmly with open arms. That's

the tradition of the music. It happens all the time and they feed you

well. Milt is one about everything you could ever listen to, Milt is playing

bass on it.

FJ:

Being around a cat like Eric Dolphy, why did you not immerse yourself

in what is coined "free jazz" (Davis appears on more than a

handful of Dolphy dates)?

RICHARD

DAVIS: They just called it free to categorize the present time, but everybody

was playing free. Everybody would just step out. I met Dolphy in 1963.

I just thought he was one of the greatest guys that I ever came across.

He was what I needed to take me to another step. He was thinking the way

I was thinking. It is difficult to tell you what I was thinking if you're

not a musician.

FJ: I couldn't play a tune with two hands and a string trio. You do realize

most people who listen to music are not musically inclined. If they were,

you'd be out of work.

RICHARD

DAVIS: Well, he was thinking the way I was thinking. The stuff that makes

you like him is the answer. He was like an angel. He was way ahead of

his time.

FJ: Any thoughts on Out to Lunch?

RICHARD

DAVIS: I don't listen to it anymore. I only listen to things maybe once

or twice when they come out. That was the time. People were into that.

People were free.

FJ: You appear on Andrew Hill's Point of Departure, Judgment, Lift Every

Voice, Smoke Stack, and Black Fire, Joe Henderson's In 'n Out, Bobby Hutcherson's

Dialogue, and Kenny Dorham's Trompeta Toccata, all Blue Note dates, were

you the house bass player?

RICHARD

DAVIS: I don't know about house, but I was there. Musicians approached

me.

FJ: Alfred Lion never asked you to do your own date?

RICHARD

DAVIS: No, I don't remember that.

FJ: The wealth of knowledge on those recordings, are you still learning

from those sessions?

RICHARD

DAVIS: You learn listening to somebody fart in the bathroom. You're always

in a transition. There is always a transformation. There is certainly

always curiosity. Looking for a bit of knowledge, that's what curiosity

is. You don't know what it is. You're just looking. Talking to a non-musician

is not easy for me.

FJ: Doesn't make for much of a social life.

RICHARD

DAVIS: When you say learning, I don't know what you mean by that. I can't

say jazz is different than any other music because a lot of musicians

are improvising that are not playing jazz. There are some great things

that are happening in Africa, some of the things that happened in India.

Jazz is an easy way to composer the music you are executing at the same

time. I can't say that it doesn't happen in any other music because I

haven't played any other music. I only can speak for the music that I'm

familiar with which is mostly jazz and European classical music. European

classical music is written out, but you don't play that the same way every

time. You interpret it different. You add here. You add there. You are

playing the same notes, but you are playing it with different players.

That is why some people would rather have a recording of Tchaikovsky being

played by Heifetz or a recording by someone else.

FJ: Are you teaching?

RICHARD

DAVIS: Yeah, bass over at the University of Wisconsin.

FJ: What is the one thing?

RICHARD

DAVIS: Just practice hard and do the best you can.

FJ:

That's it?

RICHARD

DAVIS: It's not simple. Let's say that you're always working on your voice

if you want to maintain some type of cycle. You are always working on

your voice. People will tell you that they knew it was you on that record

after they heard the first couple bars. That is proof. You can develop

different sounds over the years and you might even forget that you sounded

like that at one time. The sound is always moving.

FJ:

You played with Los Angeles superheroes, John Carter and Bobby Bradford.

Both tragically underground.

RICHARD

DAVIS: I can't answer that because I've never taken a consensus.

Fred Jung

is the Editor-In-Chief and it's in the game. Comments? Email

Him