Courtesy of Ron Carter

Blue

Note

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH RON CARTER

February 13, 2001

This is the

second time in two years that I have spoken with

Ron Carter. In most cases, I choose not to interview artists in such a

close time frame because I rarely leave much left to talk about, but in

Carter's case I was not concerned. He has so much on his plate, both past

and present, it would take me another fifteen or so conversations to get

bored. So an encore from one bassist who needs no introduction, unedited

and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's touch on your relationship with Miles Davis.

RON CARTER: I met him at a concert in Rochester, New York, the summer

before I moved to New York, the summer of '58. He was coming through New

York with a package show that had Maynard Ferguson's band, Dave Brubeck

Quartet, Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, and the Chico Hamilton Quintet,

and Miles was on the package. I met him backstage after a concert. Everyone

in my age category thought that if you want to play music, you've got

to join that band because it was the band of the day. They really sounded

great and they had really done some interesting things with group playing.

It was quite an impressive array of talented musicians to be involved

with and everyone in my age group thought that this was the band you should

join if you want to get into a good jazz band, this was the band you should

join. I was just a senior in school. Anyone who goes for three years of

college can't be intimidated by Miles Davis (laughing). He didn't act

any other way other than pleasant. I was going to take Paul Chambers and

Red Garland and Philly Jo Jones to the train station and I was meeting

them backstage to take them to my car. I was already looking in New York.

I wasn't just arriving on the scene. I had worked with Bobby Timmons for

eight and a half months, Herbie Mann for several months, Randy Weston

for a whole summer, so I was already working in New York. He still had

the best band there was and each time he came by the club to see me play,

I was at the Half Note with Art Farmer, I already had a job and I wasn't

going to leave Art Farmer's job until Art Farmer said it was OK. So I

told Miles that I would like to join his band, but I have to commit myself

for the next two weeks with Art Farmer's group with Jim Hall and Ben Riley.

I said, "If you ask Art and he says it's OK, then I'm happy to go.

If he says no, I will be here until the gig is over."

FJ: What was Art's answer?

RON CARTER: He appreciated me taking the time to be concerned about his

situation and not just leave him and he was very gracious and understanding

and said that I could leave the gig that week. So I finished the week

with Art and left the next week with Miles. My excitement was tempered

by the fact that I had already worked in New York for a while. I had just

gotten a Master's two years before. It was an honor to be in the band.

Don't misunderstand my view, but I had already started working in New

York, so I guess I was maybe less excited had I been there for the first

hour and gotten to join the band. It was a pleasure in any event, but

I was not knocked off my feet because I was already working.

FJ: The last time we had a conversation, you spoke about touring with

the Orfeu band, were you able to assemble a tour?

RON CARTER: Well, Houston toured with the band. We'd go out whenever we

could work our schedules. He's as busy as can be, so it was a little difficult

to catch him when he's got a rare moment to do other projects. The band

didn't tour. I remember that five of us had gone to Rio for a week and

three days before the band recorded. Bill Frisell, who I had not toured

with, met us in New York. I worked with Bill with some Joey Baron projects

and had always admired his playing and I would like to think at some point

we can go on the road for a brief time to play some music together.

FJ: Did critics understand the intent behind Orfeu?

RON CARTER: Well, I have met no one who didn't like it. Again, one of

the overall conversation pieces was Bill Frisell. They know him for doing

whatever he does and they couldn't figure out why I would hire him to

play on a record that clearly was not of his musical interest. I said,

"Do you ever listen to Bill Frisell play?" Because if you listen

to him play, you would know his interests are pretty broad and he plays

enough different types of his own kinds of music. You shouldn't be surprised

to hear him in an environment that while not his, he certainly fits the

slot that is necessary.

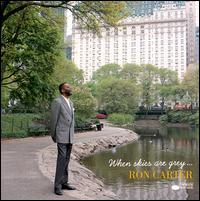

FJ: Let's talk about your latest Blue Note release, When Skies Are Grey.

RON CARTER: Harvey Mason is on drums, Steve Kroon, percussion, and Steven

Scott, piano, my general group with a different drummer. I've known Harvey

for a very long time and one of the questions asked when this record is

talked about is, "What's Harvey doing on a jazz record?" And

I kind of look incredulous because I've always known Harvey to be a jazz

drummer. He used to be with this band and with this band. I know those

records and I've heard him play, but my sense of hiring him was that he's

a wonderful jazz drummer. Whatever else he's known for doesn't make him

any less of a jazz commodity. He's an experienced studio player. He reads

well. He swings. He's got a great drum sound and is someone I've looked

forward to playing with for a very long time. We've talked about various

projects together, but this is the first one that's really come to fruition.

It was my chance to hire him before he got a chance to hire me. They (the

record label) wanted me to have a special guest on the record and for

me, it is a lot easier to do that with a drummer rather than a piano player,

who I would have to spend more time with so that they have a chance to

feel comfortable with the addition harmonic turns and the dynamic range

of the band. It takes time to do that and with a drummer, you have less

problems because you are covering fewer areas of real interest like changes

and chord voicings. Harvey is aware of that, but he doesn't play it on

the drums, so it is not so much of a complication to have a newer person

playing drums than a new one playing piano.

FJ: With Mason on this record and Frisell on the last one, you have been

able to take artists who are not normally associated with straight ahead

jazz and trust them enough to adapt to the climate you create.

RON CARTER: I bring a concept, Fred. I'm pretty organized. I'm very organized.

When I bring the music to a session like that, I've thought it through

for four or five months, everyday. I have a good sense of organization.

I'm a strong player and a directing player. All they have to do is trust

my sense of direction and my sense of feeling that this is going to work.

If they just follow my instructions and do what you do in conjunction

with this new environment that you're in, it's going to be OK. And because

they do have that kind of faith and trust and know my background of all

the freelancing that I've done, they are comfortable with my way to play

music.

FJ: Steven Scott has been with you for some time now.

RON CARTER: Well, he's got a great piano sound. He's interested in learning

music. He trusts my sense of, when I ask him to do something or my recommendations

for him to do, when I first worked with him, I said, "What you should

do is go around and watch Hank Jones and Tommy Flanagan and Roland Hanna

and watch how they use the pedals on the piano." A lot of jazz players

use the pedals, but they really don't use the pedals for what they can

do. And he took me at my word and has become a great pedal piano player,

as well as a great hand piano player.

FJ: You seem to have an affinity for Latin music.

RON CARTER: Well, I've been playing it for a very long time. I made those

records with Ray Barretto in the early Sixties, the Jobim records. I've

been in the community for a while. I've never done a record that I was

responsible for with this kind of Latin intent, but I am comfortable with

those players as well as the music.

FJ: Did you realize the ambitions for this record?

RON CARTER: What I was trying to do, Fred, was get a Latin sound with

only four people. When you think of Latin groups, you always think of

a band like Tito Puente's band, that real fiery, and those kinds of large

size organizations that have two congas, a bongo player, a timbale player,

a rhythm trap set, a bass player, maybe a guitar player, a keyboard player,

four or five horns and some singers. And I wanted to get that same kind

of impression, but with only a quartet. I'm very happy with the results.

FJ: You are?

RON CARTER: Absolutely.

FJ: Did you leave any stone unturned?

RON CARTER: My view, what I've tried to do is to go in there, we got there

at nine o'clock in the morning. We started recording at ten and by four,

we had finished the record. All that was left for me to do was go in and

do some mixing. We did maybe two takes on one song, but what you hear

is basically one take songs. I think if I can keep them focused during

the course of the recording, my approach is generally, those who are only

playing should be in the recording studio, the engineer, and the assistant

and my assistant, but basically, the studio room is not a place where

anyone who is not playing belongs when I make a record. So what I try

to do is finish the record, complete the record from ten in the morning

until it is done. Then I take an hour break and the engineer and I go

back and we mix the record an hour after we finish making it. So when

I leave the studio, at whatever AM that is, theoretically, the company

can take that disc or tape and go right to the mastering plant and make

the master. It sounds complete because the process that I use doesn't

allow for any wide spans of time for questions to creep in about, "Is

this really OK," or "Is this the right song," and "Is

this the right personnel?" I made those decisions and I am comfortable

with them, comfortable enough to take the project and run until it's complete,

which in this case may take a total of twenty hours.

FJ: Having appeared on so many records, what is the key to making a good

studio record?

RON CARTER: I think one of the keys in the studio though, when you hear

comes equally from the studio, comes with the equipment, comes in the

music, and comes in musicians. What you put in is what you hear. It is

like a free lesson actually. If you listen carefully to the recording

that you just made, you can hear things that you would not hear at a gig

or at a concert or practicing, but you hear it back right away with the

kind of fidelity and naturalness that you would not normally get a chance

to appraise or hear your playing to appraise it by. The second thing is

that the level of focus that is necessary for a good musical record. Many

recording sessions that I've done, they have it very casual and they act

all loose, in terms of they will do a take and then sit down and make

phone calls and have lunch and people will come by and hangout. They will

do a second take and then the environment is even more social and casual

and by the third tune, the intensity for making music is kind of faded

out by everybody hanging out and wanting to be on the scene. I think the

third thing that is important is to limit the environment to only those

that are making the music. If you can control their focus and not let

their interests be distracted by non-musical things, I find you get a

much better record. On my records, I have tried to do that. I've tried

to make sure that we're all on the same page so to speak and that we won't

have take fifteen and take twenty. We won't go out to have lunch after

the first song is complete and we won't have our friends come by and hang

out and make phone calls and order food. I mean, that is not what that

is for me. It's a really difficult, difficult job and the best way to

get this difficult job done is to control the environment.

FJ: With this music advocating individuality, as a leader, is it difficult

to control an environment of egoism?

RON CARTER: That's necessary. I think what a good leader does is have

them play as one. One of Miles' greatest traits was his ability to find

four other strangers and have them sound like one band after a six month

period or however often they worked. In a studio, you find people, whose

personalities you feel can be most melded into the mind of one when you

are making a record.

FJ: Do you advocate studies for young musicians rather than the traditional

experience from the bandstand?

RON CARTER: Well, I think studying is important in any industry. Certainly,

music is an industry. I think the days of guys leaving home at eighteen

and going on the road with a big band, they are long gone. You can't join

Duke Ellington's band when you get out of high school and spend ten years.

You can't join Count Basie's band or Woody Herman's band or Maynard Ferguson's

band out of high school or one year in college and go on the road and

learn how this music operates. The best thing you can do for that is to

enroll in a school that has a jazz program that will show you chords and

harmony and show you keyboard skills, or arranging skills, or composition

skills. The only thing that the schools can't teach you is how to be a

leader. That you learn on your own. I think the education system is great.

I felt schools have a pretty serious academic component, in addition to

the music program, which is also very good.

FJ: As an educator, will there ever come a time when you will put down

the bass and focus solely on teaching?

RON CARTER: No, I don't think so. I've still got some notes to find. My

theory is if you aren't playing, you will never find them.

FJ: Have you found any so far?

RON CARTER: I've found some good ones, but I think there are more available

out there and the more people you can play with and the longer a period

of time that you can play with them, the chances of finding a great set

of notes are even better. I'm looking forward to working with Roland Hanna

within the next month and he's a person whose talent I have always admired

and whose ability to help me find these notes is quite a challenge. To

put the bass down now and to play with him is a chance that I would not

want to miss.

FJ: Are you the most recorded bassist in history?

RON CARTER: That is correct. Yeah, well, I've got about fifteen hundred

(recordings) or so here and a friend of mine in Japan, who is doing a

project for his own personal library and he came up with close to three

thousand. I've made more recordings Rudy Van Gelder's as a bass player

too. I've made about six hundred recording sessions at Rudy's alone.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and needs a Saturday night

card game. Email him.