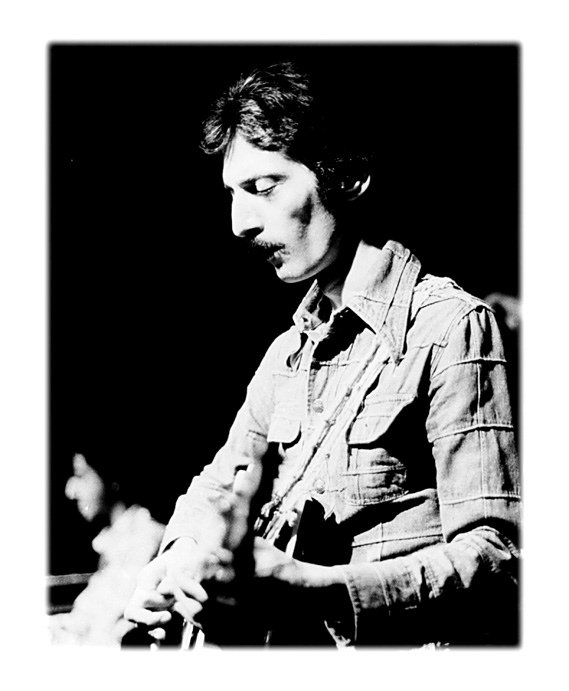

A FIRESIDE CHAT WITH PAT MARTINO

Considering

the only two things I have had to overcome are a sore hamstring and the

common cold, I have no idea or words to compare the trials that Pat Martino

has already triumphed from. Having lost his memory as a complication of

his brain surgery over two decades ago, Martino has struggled back to

prime form (some would even say better form). His latest brings him back

to familiar territory, the organ trio. I spoke with Martino via telephone,

unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

PAT MARTINO: Curiosity and the nature of wanting to be closer to my father,

who had a guitar in the house and just being curious as to what it was

like. It was a big instrument. I was three years old or four years old

and I was told that I went under his bed, where his instrument was kept

out of my reach. And through curiosity, I began to play with it, watching

the strings vibrate colorfully, cut my fingers and saw the bleeding take

place for the first time and suddenly, I was curious about what to do

with that also. So I painted some pictures on his bedroom wall. Curiosity

was the art.

FJ: Are you still curious?

PAT MARTINO: Absolutely.

FJ: With an already established presence in jazz, the guitar is a difficult

instrument to define as your own, was that reality pause for concern?

PAT MARTINO: Well, I think that it's built in to be somewhat reserved

in the sense of being an amateur and confronted with experience on behalf

of seasoned artists in any field of endeavor. And yeah, I did. But at

the time or the age that this all took place for me, which was at the

age of fifteen, I culturally moved from one vicinity of the United States

to another. And going into New York City's Harlem at the age of fifteen

with no employment and just a guitar and enough courage, maybe, to take

a chance and curiosity as to how it was to participate and to be a jazz

musician. I think that helped me to overcome the initial fear of going

out on my own.

FJ: Harlem on your own at the age of fifteen without the security blanket

of parental comfort, both mentally and financially, the moxie.

PAT MARTINO: That's true. It was not difficult to find work, primarily

because I took a job with the late Charles Earland's organ group. It was

an organ trio and we went to Buffalo, New York and I played there with

Charlie and Lloyd Price came in to where we were playing and was very

impressed with my playing and invited me to New York City to join the

big band. And it was an eighteen-piece band with some of the biggest names

in jazz that were performing with the band, including Stanley Turrentine

and Tommy Turrentine, his brother, Slide Hampton, Charles Persip, Charlie

Persip was the drummer. Red Holloway was in the band. Julian Priester

was in the band. There were some incredible players in that band. They

took me up in the band. They used to refer to me as "the kid."

These elders really took care of me and refined my experience at a very

early age.

FJ: Apart from the indispensable musical education gathered from being

the presence of such veterans, what kind of life lessons did you discover?

PAT MARTINO: Precision, in a sense to be concerned with the art of presentation,

with the necessity of responsibility, with the courage to be spontaneous

enough that new experiences musically would arise, and if not so, to replace

that with lack of interest on their behalf. Quite a number of things that

I think more experienced individuals in any field of endeavor have a tendency

to naturally present this to younger people who have just come into it

for the first time and lack experience.

FJ: In my youth, I never appreciated the lessons that were taught to me.

Were you able to savor the moment?

PAT MARTINO: That's a tough question to answer, Fred, because I don't

know whether I personally had that or it was a result of how I was accepted

in the community. If I was accepted with more credibility, I would proceed

along the lines that brought that about. If I failed to be accepted from

something that I believed in, I found it necessary to continue to believe

in that, to have faith and to have credibility with regard to my own ethics.

I think that goes back to childhood in terms of my upbringing. But I do

think that it was necessary to participate in a different community and

to see the reaction to what I had to offer, as well as wanting to be part

of that community and offering that interest to everyone that I had met

at time.

FJ: How did you initially approach the instrument?

PAT MARTINO: I approached the instrument in a real time improvisational

context. In other words, what I couldn't understand about the instrument,

I fulfilled through improvising around those obstacles. A good example

is when I was a youngster at the age of twelve and my father brought me

to guitar teachers for the first time, I had a lot of trouble, personally,

finding interest in what they presented to me as a responsibility within

a student-teacher relationship. None the less, when my father would come

home from work and the time came for me to practice and play in front

of him, I stood there with my teacher's music book on a music stand and

my father sat on the sofa reading the newspaper, relaxing and listening

to his son. I stood there looking at the book as if I was reading it,

but I was improvising and that's how I learned how to improvise with precision.

At the last time prior to the lesson coming up at the end of the week,

I did put a little bit of time in it and immediately memorized it and

played it well for the teacher as well.

FJ: Does the kind of precision that is attainable in improvisation exist

in life?

PAT MARTINO: It is in life. In fact, its application in regards to music,

painting, or any other form of art, I think, is secondary to the source

that it comes from. I think it comes from ingenuity and I think it comes

from logic, not as much as it comes from theory, although theory is a

result of it. I think that, yeah, it's quite an interesting thing that

does occur in life. It takes place if I have to go out a mail a letter

and I know where the mailbox is and I have a few moments to use how I

would like to use them, I may walk in the opposite direction to the next

mailbox that I don't know where it is and I will find it and if not, I

have enough time to come back to the one originally that I had chosen.

I will improvise my way back to it. In the meantime, I will experience

a lot of new things. It's like killing two birds with one stone.

FJ: In 1980, at what should have been the height of your career, you suffered

a devastating brain aneurysm that caused the loss of memory. Through meticulous

diligence, you were able to return to playing form.

PAT MARTINO: The most difficult part of recovering a destination was,

not only the definition of that destination, but also, the decision on

my behalf and that came about primarily due to the amplification of boredom,

which came through procrastination in depth, putting off making a decision

for such a long time, in the process of recovering and being surrounded

with forms of therapy that came from loved ones as well as professionals,

distractive in the sense of my original destinations and not necessarily

demanding the responsibility as decisive as it should have been caused

me to become more and more bored until finally, I was so bored that the

only thing I could think of was I took advantage of the one thing that

I knew how to do. It was quite a bit similar to riding a bicycle from

childhood. I think that if I were to pick up a bike at this particular

point and I haven't ridden on a bike for many years, but since I did absorb

the use of that machine at a very young age, it became subliminal and

I may get back on the bike and fall down a couple of times, but I know

how it runs and I know what to do with it. The same thing was with the

guitar and it was the same reason. The simplicity of it was no real difficulty

involved in terms of re-mastering it and using it as a vehicle to the

destination that I had chosen.

FJ: Upon listening to your earlier recordings, do you find that your style

had changed when you embarked on learning the instrument once more?

PAT MARTINO: The nature of what I had learned through listening what was

done on record was not from my choice. Since I did recover when I had

the operations, here in Philadelphia, I recovered in mom and dad's home,

in their presence. It was they who chose to play that music and each and

every time I heard that music, it was one of the most uncomfortable confrontations

of what seemingly was a responsibility on my behalf to reconstruct for

their needs other than mine. It was very difficult. The difference after

all of that took place and was surrounded by boredom in the meaningless

of all of it, brought about a neutrality in regards to the nature of the

instrument's importance, as well as the lack of importance in music itself

until a decision is made as to what one would like use that as a vehicle

for it to achieve amongst other surroundings. So it became more important,

the more that the ability to mechanize these gifts once again became more

of a responsibility to allow that to happen naturally and with that begin

to see the people that brought me to these situations that I found myself

amongst social interactions because of that ability. Because of that,

it became neutralized in regards to any significance of it.

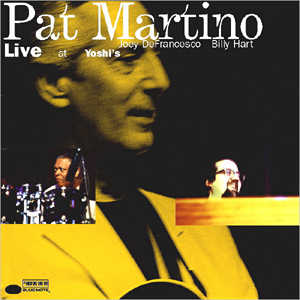

FJ: Live at Yoshi's, your latest project for Blue Note, harks back to

your earlier apprenticeship with Charles Earland.

PAT MARTINO: Well, I think that it is well understood, in terms of response

by any artist in any field that it's never comfortable before a performance

(laughing). To go on stage is always a nervous event until you're on stage.

It is like coming from set time to real time and that still existed and

it will always exist. But, yeah, Fred, there is a great deal of enjoyment

in terms of its authenticity, more so than I could remember about a lot

of other things, also, the fact that it helps to retain the feeling of

seasonal emergence of a lot of different things that I never want to go

away. When Hammond B-3 comes back, it brings me back to the Sixties and

when I used to do so in that particular instrumentation with other major

players and I haven't for a long time. It brings that back, that authenticity

with that particular era as well as the idiom and of course, under different

circumstances, where the culture itself had evolved and changed. It enhances

it with new ingredients. It's a very exciting experience and I hope, to

be honest with you, Fred, that all of these things continue their circular

seasonal appearance.

FJ: What is it with guitarists and the B-3 organ?

PAT MARTINO: There is no other sound than the Hammond B-3. Due to the

fact that just the manipulation of its pedals creates vibration in the

floor that you're standing next to it, which you can't get sampled. You

can resample the sound of it and reproduce it on one of the finest synthesizers

made or any of them, but the one thing that is missing is the pedals being

tapped by the foot of the performer, the player. Another thing that's

missing is the swerving rotation of the Leslie, in the Leslie speaker,

the Leslie cabinet. When it goes fast and then it slows down and the second

time, you're hearing vibrato being altered in terms of the tone itself.

All these things produce an experience that can't be achieved with any

other instrument.

FJ: Having a renewed awareness, what do you appreciate most about your

life these days?

PAT MARTINO: That's an awesome question. I appreciate more than anything,

the repetitive ingenuity that invention itself contains, that authenticity

comes to the surface when repetition signifies its presence. It is a very

interesting experience to see the twelve tone scale and see the repetition

of that logic in twelve tones of music and in twelve eggs in a dozen and

in twelve months in a year is a significant reminder that you're on the

right track. And I think that inventive ingenuity is one of the most exciting

forms of interface from a confusing carnival of different faces, all joined

as one in a very unified whole and that's the human race and I see that

in all other things too, the ingenuity of creative structure. That's the

most exciting thing to me.

FJ: Sounds like the fire still burns within.

PAT MARTINO: I sure do, Fred. It's really a pleasure, Fred.

Fred

Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and thinks What's the Worst That

Could Happen? is the worst that could happen. Email

Him.