Courtesy of Pete Christlieb

C.a.r.s.

Criss Cross

Records

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH PETE CHRISTLIEB

Three things I am certain of when it comes to Pete Christlieb. One, he

can shoot the shit. Two, he is certainly not full of shit. And three,

he can play the shit out of a tenor. Simple, but that’s Christlieb,

simple, no nonsense, straight, no chaser. Christlieb is yet another Los

Angeles musician (one in a long line) that has gone largely ignored in

this city for too long. But alas, my head hurts from banging it into the

wall on that sore subject. Folks, Pete Christlieb, unedited and in his

own words.

FRED JUNG: Let’s start from the beginning.

PETE CHRISTLIEB: I come from a pretty musical family. There was music

in the house all the time. My father worked primarily in the motion picture

business. He worked at 20th Century Fox. He was in the orchestra and he

made about 750 motion pictures at 20th Century Fox. He played bassoon.

They had a lot of chamber music going on in the house. There were rehearsals

all thetime and we went to concerts all the time and my first instrument

was the violin. They weren’t too thrilled that I had heard some jazz

and wanted to get a saxophone and try doing that. Fortunately, for me,

somebody had left some Chet Baker/Gerry Mulligan records laying around

the house and I got them and I played them and just fell in love with

the idea of creating your own music. I got a tenor. I got familiar with

that and was still playing violin in the orchestra and the tenor on the

side. I had to play jazz. I was really hooked on it. I got a bunch of

records. One begot the other. Listening to Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker

and then you are exposed to Zoot Sims and Al Cohn and then you are exposed

to Clark Terry and you are exposed to Phil Woods, Charlie Parker, John

Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley. Cannonball became a good friend and when

I was growing up, I used to follow him around town here and hang out with

him and talk about music. He was a real nice man. I got my first job going

on the road with a band right out of high school. It was a lot of homework

and stuff that I didn’t want to do. I just wanted to play. So I went

on the road and stayed out a year with that band. Then I went from that

to Woody Herman’s band for a short stint. Then I came back into town

and went with Louie Bellson’s band and I played with Louie Bellson

for many years and it was because of Louie Bellson that the Tonight Show

became a regular gig for me. Louie was doing the show at the time and

they needed a tenor player and he made the recommendation and got me in

the door and that gig went for twenty years.

FJ: A day gig makes life easier.

PETE CHRISTLIEB: You ain’t got income, you don’t have nothing.

It takes two incomes now. The deal with the Tonight Show was you were

exposed quite a bit to the public. It was a very popular show. It was

a very good musical situation for me, being exposed as a soloist all the

time. It was a steady gig, but I will tell you something, Fred, the shoeshine

guy made more than we did. We never got tips. We got scale, which was

a hundred and seventy-five dollars a night. You went in there from three

in the afternoon until six at night and then you went and did other things,

go play in clubs and record dates in the morning. It was great supplemental

income. Doc (Severinsen) had his bands that traveled on the weekends,

so it was up to us guys who had the regular job to give up days of the

week so those guys could work and stay in town and go out with him on

the weekends.

FJ: Alas, all good things come to an end.

PETE CHRISTLIEB: The Tonight Show ended and they just said, “Next

week, the show is over,” and we hit the streets. The next guy to

come through the door was the guy who fired us. They fired everybody.

There was no love lost between Doc Severinsen and Jay Leno.

FJ: The Tonight Show with Jay Leno is not the same show.

PETE CHRISTLIEB: It is quite a bit different. The role of the band is

so insignificant now. Whereas before, it was a variety show where people

came on and did their song and dance routines and the band was part of

everything. Johnny was responsible for making people’s careers instantaneously.

If you were a comedian and you got a shot on the show and you were halfway

funny, next thing you know, you got your own show. You name it, they got

their start on the show.

FJ: What I lament about being a lifelong Angeleno is the obscurity of

the musician’s role in this city.

PETE CHRISTLIEB: Oh, yeah. It is tough for new guys who come to town because

there is an “X” amount of work and a hell of a lot of guys to

do that too. I was never any good at politics and so the only reason I

am doing all this stuff is my ass is so old and I have been around here

so long, I am wallpaper. I guy says, “Why don’t you do a solo

like Pete Christlieb?” I said, “I am Pete Christlieb.”

He says, “No, he’s dead.”

FJ: Why have you not recorded more?

PETE CHRISTLIEB: The last one we put out was called For Heaven’s

Sake. We spent sixty thousand dollars on it. It was a beautiful album

and everyone on the album got something to play. I thought it was a great

album and it went virtually unnoticed. I sell them off the bandstand.

That is the way a guy can survive in the record business. The store business

and distributors are scoundrels. It was a common deal to take records

and not pay for them. What is even worse is when they got tired of the

records that they stole from you, they sold them for a buck a piece in

the other markets and destroyed your other business. That was very discouraging.

I hate the record business. I think it is the worst.

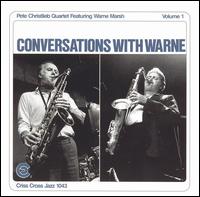

FJ: What is the story behind Apogee and the two volumes of Conversations

with Warne?

PETE CHRISTLIEB: Warne and I worked in Clare Fischer’s band together.

I helped him build the studio that he did his first album in with a trio

and I said, “Why don’t you and I make an album together?”

And we made a lot of music happen without a piano. I had a cassette of

the thing that Warne and I were recording. We were recording in a studio

that I helped build. We made this album and we were going to put it out

on our own and I played it for Steely Dan and they loved it. The next

thing I know, they are telling me that we got the deal and they are going

to produce the album. So we put the album together, the Apogee album with

beautiful music. Joe Roccisano did some of the best arranging anybody

ever heard. It was Warne and I and Nick Ceroli, Jim Hughart, and Lou Levy.

We went in the studio and in three days, we made jazz history. They wanted

to drag this thing out and record some new stuff everyday and it was completely

counterproductive to the fact that we put an album together with an idea,

with a concept, and it all worked out. It is not a haphazard which way

the fucking wing blows here. We put it together and it was beautiful.

The next thing I know, they are throwing all our work away. Some of the

best things that I ever did in my life with Warne Marsh are locked in

dungeons at Warner Bros. I tried to buy one track to put on another album

and they said, “Give us fifty thousand.” They took the project

to New York and they squandered it. When they put the album out, most

of the tunes we wanted on the album were discarded. The notes, the mixing,

the album cover was all made up by them without anybody’s approval

here. I went into Warner Bros. and their jazz department was in the basement,

a broom closet with a payphone. Conversations with Warne was the album

that we made. A guy from Holland bought it. He bugged me for a year and

finally I sent him the stuff. He gave me thirty-five hundred bucks and

I gave everybody involved, including Warne’s widow, I gave her money.

He took it and he cut it up into little pieces and he made two albums

out of it.

FJ: And the future?

PETE

CHRISTLIEB: I can play seven nights a week in this town for eighty dollars

a night. I am already playing two and the other nights, I need to rest

from having so much fun on the others (laughing). I’ve got to dry

out. I am playing at Charlie O’s. Every Friday night, I play at Fitzgerald’s

at the Hilton Hotel. I just got back from Nebraska where I played for

six, seven hundred people in an auditorium and you come home and you go

into a joint and play and people are talking real loud while you’re

trying to play and you don’t make any money. It is better to be out

of town and play for people who are dying to hear you play. This town,

like you said, it is heartless. It could be a great musical Mecca, but

a lot of great musical scenes have died on the vine here because a lack

of interest. Steamers, I play there once in a while, but I keep telling

Terence that if I were a cab driver, I would make more money dropping

somebody off than what he is paying me and I wouldn’t have to stick

around a play three sets. That is ironic, but that is the truth. They

don’t pay any money. You get a hundred bucks for playing the night

and you go to Albertson’s and try to buy something for a hundred

dollars. You’re going to get a package of chewing gum, a roll of

toilet paper, and what else? For me, I am leaving town next week. They

like me in Seattle. I have been going there. I have a lot of friends there.

I play there. I have a fan club there, so I go there.

FJ: So you are basically playing locally to keep your chops up.

PETE

CHRISTLIEB: To keep your chops up. I hate practicing, so if they pay me

a hundred bucks to go practice and then I will buy a loaf of bread on

the way home and the money’s gone. There was a new joint coming around

called Clancy’ s Crab Shack and they were having jazz. I went in

there. I had a good rhythm section. We packed the joint and we played

our ass off. They said, “You want to eat?” “Sure.”

They hand me the menu and it’s a kiddie menu. This is a crab shack.

You look in the restaurant part and people are eating Dungeness crab and

lobster and steak. You get the choice of a little Mac and salad with one

crouton and a coke. You want a drink, you pay full price for that. I said,

“That is bullshit. Give me a salad and a crab dish and a drink,”

forty bucks. I went home with about fifty bucks out of a hundred. I said,

“You chicken shit. That’s it. I will never come through the

door again to play in this place.” There is something wrong with

this attitude. They love you over there at Charlie O’s. They pay

a hundred bucks and I can’t buy a drink, I couldn’t buy a meal.

They treat you right. Maybe because I am getting old, but I like playing

from eight to twelve and not this nine to one. When I am out of town and

go to Europe, we play two sets. We just blow our ass off and then there

is time afterward to drink pilsner and hang out with the guests. And man,

that is good beer. You can’t get that here either.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and is the ace of spades in the Iraq

poker cards. Comments? Email Him