A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH WALTER NORRIS

Life

for a musician is a difficult one. Life for a jazz musician is the most

difficult of all. There is no crowd surfing going on at jazz concerts.

Most shows I have been to don't have enough people to fill a VW Bug on

most nights. I have always been humbled my jazz musicians. Because of

his wonderful music and by virtue of the mere fact that a dear friend

of mine, tenor saxophonist Benn Clatworthy knows him, Walter Norris has

been and continues to be one of my favorite pianists. Norris is one of

one a handful of pianists that Ornette Coleman has ever used. That such

prove leaps and bounds of his musicality and understanding of his instrument.

I am honored to shed light on Mr. Walter Norris, a shining star indeed,

unedited and in his own words, from Germany no less. Thank God for the

internet.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

WALTER NORRIS: Since my mother played, it was only natural that she wanted

me to study piano with a good teacher, and she found, in '36, the best

in Little Rock, a church organist by the name of John Summers, with lessons

twice each week which I enjoyed and took seriously until '50 when I departed

from home. One morning in '40, listening to the radio before leaving for

school, the disc jockey played a boogie woogie recording probably by Albert

Ammons or at least someone good who impressed me. I could not stop thinking

of this music during school and after returning home that afternoon, I

started playing boogie woogie; not a great feat considering harmonically

it is only blues, using triad, sub-dominant and dominant chords. But,

although I thought of this as a new music, I still continued with classical

studies. In 1942, I joined Howard Williams' rehearsal band; he was only

two years older than I, and this neighborhood band played their first

dance job in January 1944. I was paid $10.00 for the evening and walked

on clouds for the longest time afterwards.

FJ: You played with Ornette Coleman for a time, so much has been written

of him and yet you had an insider's unique perspective on the music and

the man.

WALTER NORRIS: Ornette Coleman is a lovely human being who had to play;

and only his way was possible. He had no musical schooling but he nevertheless

wrote two or three riff-charts every morning and with Don Cherry, Ornette

would play these new pieces during afternoons. Before recording "Something

Else" we rehearsed the titles, usually at my house, three times each week

for at least six months before the record date, and each time we rehearsed

a title, there was a small change, which I notated on manuscript. At the

recording, each title was somewhat changed again. To an organized mind,

I'm describing an unorganized method, but I'll argue that it is a natural

creative process. His compositions on that date in '58 still have charm.

FJ: You were also the musical director at the Playboy Club for a few years.

That had to be an interesting situation.

WALTER NORRIS: The first four years at the New York Playboy Club were

fantastic because Heffner could not obtain a Cabaret License. According

to the city's regulation, only string instruments could be used; meaning,

no drummer, horn or singer. Pianists played jazz as they wished because

management felt lucky to get anyone who could keep an audience in their

seats (paying a cover charge) for forty-five minute performances repeated

four times each night. The pianos were new Steinways grands and tuned

by a Steinway technician twice each week. I followed as Musical Director

after Kai Winding and Sam Donohue and was eventually made Entertainment

Manager. So, I was responsible for hiring musicians, entertainment and

the paper work. The musician's dressing room had a Steinway with a lock

on the door, so we had a great time even playing for each other after

finishing work.

FJ: How was the vibe in New York at the time?

WALTER NORRIS: New York, in the sixties, had many difficult problems.

The bass-guitar with amplifiers and the Ghetto Revolution created tension.

Jazz recordings of high-pitched saxophones screaming and sounding much

like animals being slaughtered. There was more anger and harshness in

jazz performances. I admire John Coltrane's music but I remember an evening

at the Half Note where I had to leave because my ears could no longer

tolerate the madness of volume.

FJ: Let's touch on your tenure with the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra.

WALTER NORRIS: One Monday night in April '74 at the Village Vanguard,

I substituted for Roland Hanna, who ventured on his own, with Thad & Mel's

band and for me it was a dream come true. Joining the band, we toured

Europe and Scandinavia that summer. I remained in Munich after the tour

to record Drifting with George Mraz for ENJA Records and returned to New

York the following morning. Thad's musical talent was incredible. He was

a natural conductor in that you always knew his intentions by his gestures

and his playing had that other world quality that also remained traditional

and always beautiful. I still believe his was the best of all big bands,

the piano was featured on all but about three or four arrangements. I

remember many concerts where audience-response was absolutely intoxicating.

Thad was perhaps the most talented of all arrangers and he was blessed

with an ability to figure a solution immediately whenever there was a

musical problem. For this reason he recorded, as sideman, on so many excellent

jazz studio dates. If there was a problem in the music, he saved the "date"

with his suggestions, which were always better than ideas suggested by

others. I left this dream-band in Munich at the end of January '76 for

a three month European duo tour, which never materialized. As a result,

I was stranded in Scandinavia but worked with only eighteen nights off

throughout a period of seven months. I returned to New York, joined Charles

Mingus for three months and received a telephone call from Berlin to join

the SFB radio orchestra.

FJ: Why did you move to Berlin in the late '70s?

WALTER NORRIS: The real reason I moved to Berlin was to leave Mingus.

He was always great to me but one night while talking in the dressing

room I made the unforgivable mistake of addressing him as Charlie instead

of Charles. His eyes crossed with the expression of a raging bull but

at this very moment the stage manager announced that we were to play immediately.

Having the ability of a gentleman, Mingus never mentioned my unforgivable

mistake but I knew my days were numbered. I waited until he was in Woodstock,

New York and phoned him that I was moving to Berlin and joining the SFB

Studio Orchestra. Now he was really angry and screaming, but I knew he

couldn't drive to New York City before my plane departed from JFK airport.

I welcomed living in Europe for I knew that I would have a perfect Hamburg

Steinway, at the radio, maintained by one of the greatest piano/technician/tuners

on this planet. I was completely insured, medically, with a five-year

contract and an enormous amount of time off for practice. In a way, I

was sponsored by the radio station.

FJ: How was state of European jazz changed since?

WALTER NORRIS: European improvisers have improved immensely since 1977.

More American musicians were imported because of a low dollar exchange

rate, with a high dollar rate, and fewer travel from the "States." Books

on improvisation and transcribed solos helped. Also listening to recorded

music and by attending concerts, the Europeans learned and improved. Also,

they benefited from club and studio work.

FJ: Are European improvisers becoming stronger than their American counterparts?

WALTER NORRIS: Of course! What I find missing most, is the study of counterpoint

and I believe very few jazz improvisers, Europeans included, have ever

bothered. Austrian musicians take counterpoint more seriously because

of Gradus ad Parnassum (1725) written by Johan Josef Fux in Vienna. This

book is translated in English by Alfred Mann and entitled, "The Study

of Counterpoint." Without studying counterpoint, some degree of musical

intelligence is missing.

FJ: You had a long term relation with Concord Records, where you recorded

a gripping album with Joe Henderson, your thoughts on Sunburst.

WALTER NORRIS: When Concord suggested that I record in quartet, I said,

"Get me Joe Henderson and if not, try Bobby Hutchinson." I had listened

to each of them in Berlin and felt these two to be the best choice possible.

Producer John Burk phoned and said that Joe accepted and I told him we

should use Joe's bassist and drummer because he'll feel more comfortable.

Henderson is a study in intuitiveness, a pleasure to work with and was

no less than brilliant throughout the date. Of course, I liked this recording

then, feel the same way listening now and since it's musical, it holds

up well today. At the end of the first session the engineer discovered

one of the speakers not functioning and now we had to re-record two titles.

Joe had just left the building, so that additional work was scheduled

the following day. But, I arrived early the next morning and recorded

"Rose Petals" in trio before Joe arrived and we still used all of our

time completing the date, and this is the reason for a trio title being

on my quartet date.

FJ: What made you decide to form your own label (Sunburst)?

WALTER NORRIS: Because I want the entire CD production to reflect my sense

of aesthetics and by selecting the designer, photographer, writer for

the liner-notes, studio, instrument and engineer, it all can be achieved.

I had the Steinway tuned again for the second day's recording at Systems

II with bassist, Mike Richmond. Few labels would bother with the added

expense.

FJ: Was it easy?

WALTER NORRIS: Of course, I knew it would be difficult and it has been,

but usually the problems are with people involved for the bar code, the

incorporation of the company, the pressing plant, printers. They will

promise anything and rarely deliver as promised.

FJ: What is Sunburst's mission statement?

WALTER NORRIS: The mission of Sunburst Recordings is to produce CDs of

quality and musical taste that I approve of. I intend to record only a

few more productions of myself in different settings, write an autobiographical-novel

and complete my so-called career in jazz. I'll be sixty-nine at the end

of this year and I'll consider myself lucky if I have ten more productive

years with sufficient health because strength and energy deteriorates

more rapidly at this stage of life.

FJ: And the most difficult thing about running a label?

WALTER NORRIS: The paper work.

FJ: Should younger musicians do the same?

WALTER NORRIS: Never! Owning a label takes too much time away from the

music, but this I can afford at my age.

FJ: What should they concentrate on then?

WALTER NORRIS: They should concentrate on practice, playing and their

musical development.

FJ: Do you personally feel that your music has progressed through the

years? If so how? And has it come at a cost?

WALTER NORRIS: Well, I hope people notice that my playing has progressed

through the years. I'm on a re-issue of Jack Sheldon's Quartet & Quintet

from '54 on Pacific Jazz, and I sound like a young wild one, another,

The Trio, with Hal Gaylor and Billy Bean from '61 on the Fantasy label,

and next month a second CD, Rediscovered, of this trio will be released

on String Jazz Label (stringjazz@musicweb-uk.com) in England. I practiced,

played, developed, and honestly did so, "around the clock." Yes, there

was a cost, my wives paid dearly and I lost the first two because of my

persistent practice.

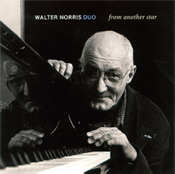

FJ: Your thoughts on your new release from your Sunburst label, From Another

Star.

WALTER NORRIS: I selected three standard titles that I wanted documented,

"Yesterday's Gardenia," "All the Things You Are," and "Tiger Rag." I chose

"New Flame," composed by my stepson, Gregoire Peters because I think it's

beautiful and the form is slightly different. I composed the other titles

because I could and needed to do so. When I compose, I find a musical

problem and work on it until "something" comes to me and the result is

the title. I do not try to dream-up a theme or wait for inspiration to

encourage me. But in programming the CD, I wanted the listener to play

it again after the last track, and I think "From Another Star"(the first

track) is refreshing after, the last track, "Tiger Rag."

Fred Jung is Editor-In-Chief. Comments? Email

him.