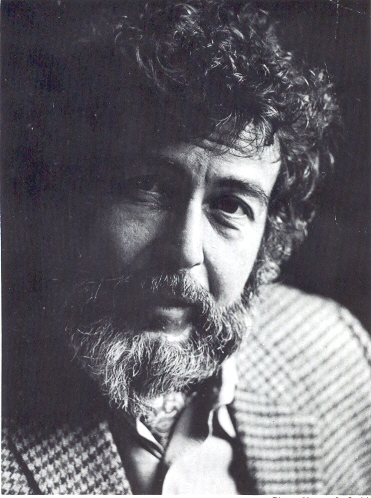

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH NAT HENTOFF

FRED

JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

NAT

HENTOFF: It was jazz that did it. When I was about eleven years old, I

was going on the main street in town and I heard music coming from a record

store. They had public address systems then and it hit me so hard that

I shouted out loud, which was not quite the proper thing to do in Boston

in those days. I rushed into the store and asked what it was and it was

Artie Shaw's Nightmare, and that brought me into the whole jazz scene.

It was the Depression and so I was working on a horse-drawn fruit cart.

I was the delivery boy, but whatever money I had, I bought Basie and Bessie

Smith and all that. Although I didn't look my age, I was able to get into

nightclubs when I was about fifteen. I heard Sidney Bechet. There were

wonderful Sunday sessions with people like Wild Bill Davison coming in

as guest stars. When I was nineteen, I started in radio at a station in

Boston and the boss allowed me to have a jazz program when they couldn't

sell the time on that hour and eventually, we did remotes from nightclubs,

the Savoy and later, George Wein's Storyville. So I got to know Duke Ellington

and Dizzy Gillespie and just about everybody who passed through. That

was a great learning experience for me, not only in the music, but a lot

of these jazz people were larger than life, more than any other adults

I knew. They traveled a lot. They knew a lot. But most of all, they were

very independent. They had to be themselves when they improvised. As Charlie

Parker said, "Whoever you are, your whole experience comes out in

what you play." And they were like that. They were irreverent, but

often very generous. I admired them greatly and still do.

FJ: What was it about jazz music that struck such a personal chord with

you?

NAT

HENTOFF: Well, these were people that have to speak who they are and how

they feel at the moment and that goes back beyond that to their whole

background. As Jo Jones, Basie's drummer said, "You can't fake it."

Anybody who has had any experience listening to music can tell the people

who are just jiving, just playing licks in the old term, running up and

down to show how many notes they can play, and the ones who are telling

a story. That was a phrase that was very current then. I once interviewed

Lester Young and he was talking about Frank Trumbauer, who was best known

for recording with Bix Beiderbecke and he played the C-melody saxophone,

and Lester Young said that when he was coming up, Trumbauer influenced

him more than anybody else. It wasn't only the lucidity of his playing,

he said, "He always told a little story." And that is what jazz

is all about. It is telling a story and being free to tell the story you

want to tell.

FJ: During you tenure as the associate editor of Down Beat and editor

of Jazz Review, you were able to witness firsthand, the extraordinary

development of the music, while shaping the direction of jazz journalism.

NAT

HENTOFF: I think what we did, I say we, the ones who were with me and

worked on Jazz Review, that was Martin Williams. That was the only magazine

then, and it may still be, that was written entirely by the musicians

themselves. I had sort of a press review, but it was the least important

part of the magazine. I think that was more important than anything else

that I was involved with at Down Beat or anywhere else because there was

still that myth at the time that jazz musicians were articulate on their

instruments, but not very verbal, not very intellectual, if you like,

not very analytical in terms of what they were doing, and here were these

musicians writing record reviews that made me very embarrassed as a record

reviewer. I think the most interesting thing for me was I was still in

Boston and I had trouble at first with Charlie Parker because I grew up

on Johnny Hodges, Benny Carter, that kind of tone, that kind of way of

swinging. Then I was interviewing, I think it was Coleman Hawkins, and

in those days in radio, we had turntables that you could put a 78 rpm

on it and then bring it down to 33 1/3 and whoever I was interviewing,

musicians said, "I want you to play Bird at 33 1/3." Then I

understood what was happening. That made it a lot easier for me with Coltrane

and then I became swept up, not only in modern jazz, but one thing I never

lost was the feeling of continuity. Ellington was one of my teachers.

He was very kind to me when I was a young man and he would often talk

about how he hated categories. He hated putting things in a timeframe.

He said that the whole thing about jazz was that every once in a while,

somebody comes along who is an originator and eventually, other people

follow him. He also hated the word "jazz," by the way, Fred.

He thought it connoted more than he wanted it to connote. In any case,

his whole mission as he saw it, was to portray in the music, the history

of black people in America, not only their music, but their life experiences,

which were inexorably intertwined with the music. In the Twenties, he

told me, he went to Fletcher Henderson and said, "Why don't we stop

the confusion about what we're doing and what other people think we're

doing and simply call it black music." Well, it was too much for

Henderson. Then years later, Duke said, "It's too late for that because

there are so many white guys and all kinds of people coming along and

they play it authentically too."

FJ: Cecil Taylor, Charles Mingus, Abbey Lincoln, Booker Little, your sessions

for the Candid label certainly were indicative of Duke's ideology.

NAT

HENTOFF: That was a jazz man's dream come true, that I was able to record

whoever I liked. The label came about because Archie Bleyer, who was then

well known as himself a musician and a leader and also he was the music

director for the Arthur Godfrey Show, which was very popular on CBS. Archie

had a commercial label that was doing very well with Andy Williams and

he thought he owed it to jazz to have a side label and that was Candid.

He never interfered with anything I did. I don't think he liked much of

it. I told him up front that this was not going to make him a lot of money,

if any. It will take a while for these recordings to break even. But at

one point, I guess it was less than two years or something like that,

his own company wasn't doing well and that was the end of Candid, but

we had a ball. I did a fairly large number of recordings in a short time.

And I only recorded people I liked. I did what Norman Granz did. I wasn't

thinking of sales figures. So that did run the gamut, but except the gamut

again was part of a continuity. One of the sessions I most enjoyed was

Otis Spann, who was then the piano player with Muddy Waters and himself

a blues singer, very deep blues singer. Muddy, himself, said at Otis'

funeral that nobody sang the blues as deeply as he did. It went from Muddy

Waters to Cecil Taylor, to Mingus, to Max Roach, to Abbey Lincoln and

the Freedom Now Suite. It was a great time.

FJ: It was bold to record Cecil Taylor, who at the time was being asked

by club owners to stop playing.

NAT

HENTOFF: Yeah, as a matter of fact, he did a session once and I think

it was Jo Jones, who got so annoyed at him that he threw a cymbal at him.

There is a common language in the music and the blues pretty much exemplifies

that. I remember when I did sessions, I rarely gave any kind of instructions.

All the people that I recorded were all part of that continuity. Sidney

Bechet has a wonderful biography, Treat It Gentle and he says that you

can't stop the music. It keeps evolving. It keeps growing. That doesn't

mean you forget the roots. I mean, Charlie Parker was a strong blues player.

Dizzy said that he was so good at the blues that he made Dizzy feel inferior

as a blues player. I knew Ruby Braff very well and Ruby told me that he

once met Charlie Parker and they were talking about music and Ruby was,

to some people, a traditionalist, a classicist. I mean, Louis Armstrong

was his idol. Bird said to Ruby, "I dig what you're doing. You really

have that melodic sense and you feel the blues." Again, I have no

patience with these compartmentalizations of the music.

FJ: You have long been a proponent of education. In California, there

is a particularly troublesome fiscal crisis and during times of budgetary

difficulty, the first cuts are educational and within that, music and

arts programs. Mortgaging the future will have its consequences.

NAT

HENTOFF: That is so destructive because aside from the integral value

of music and art, it is also a gateway for kids who are made to feel by

some of their teachers that they're dumb, but they're not dumb. Their

interests get quickened if they understand the music and if it is a good

program and they begin to play instruments themselves and they get a sense

of self-worth and that leads to their expanding own potential and their

own understanding of what being educated is. One of the things that I

find is so sad here in New York, and I suspect it is going on in California

too, the budget cuts often hit libraries, public libraries. Forget libraries

in schools. In most schools now in New York, there isn't even a librarian,

let alone a library. But the public libraries, I remember we had a fiscal

crisis about ten years ago and I saw a bunch of kids walking around and

I asked where they were going. They were looking for a library that was

open. That, to me, is a very strange way of allocating public funds.

FJ: You have long been a champion of the Bill of Rights. For generations

of young Americans, the Bill of Rights is nothing more than an afterthought.

How detrimental is this current ambivalence?

NAT

HENTOFF: We are seeing the fruits of this lack of education in all the

schools from kindergarten on through graduate school. For example, in

the major universities, American History is no longer mandated, let alone

a history of the Constitution, how we got these rights and what it took

to keep the so called "guarantees" in the Bill of Rights. The

result is, although there is a growing resistance, which I find very heartening,

to what the Attorney General, Ashcroft is doing with the enthusiastic

support of George W. Bush. We have never had so serious and systemic,

a weakening of our fundamental liberties as we have under this administration.

George Orwell could never have foreseen the degree of electronic and other

surveillance because the technology wasn't nearly advanced in his time

as it is now. We have a situation now, and this is now in the courts,

and few newspapers have been properly indignant about it. Most Americans

do not realize that the President, alone, on his say so, can and has already

done this to two Americans, declare an American citizen an enemy combatant

and immediately put him in a military brig in this country without charges,

without access to a lawyer, without access to anybody including his family,

nobody but the guards. This is the most dangerous assault on fundamental

due process, fairness, which is the instance of our system of justice.

And while there have been a few indignant editorials, particularly in

the Washington Post, I don't think most Americans know about it. That

is because the schooling we get on our basic liberties and why we are

Americans is so weak that most people don't know their own liberties and

rights so how would they get angry and concerned when other people's liberties

and rights, including American citizens, are being eroded by this administration.

By the way, Fred, I am not partisan on this because Bill Clinton was just

as bad. He was tone deaf on civil liberties and the bill that he signed

in 1996, the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act gave John

Ashcroft a lot of the basis for what he is doing in the Patriot Act, like

roving wire taps, like the use of secret evidence, this really gross misuse

of material witnesses, and material support to so called terrorists, where

people get locked up with no real charges against them, but they are held

as material witnesses indefinitely.

FJ: Systematic of 9-11, musicians I have spoken with of Middle Eastern

or Asian decent have often been confronted with the consequences of racial

profiling. Is profiling ever warranted, even under the guise of national

security?

NAT

HENTOFF: Anything that involves collective identification of people, when

it is not a specific person, where there is at least reasonable suspicion

and if you are going to search him, probable cause that he or she has

committed or is about to commit a crime, all of that is a violation of

due process. It was very interesting and I don't think there was enough

coverage of this. The Justice Department has its own Inspector General.

He is independent. He was not appointed by Bush. He was appointed by Clinton

and he is still in office. He came out a few weeks ago with a scathing

report on what Ashcroft did in that roundup, that dragnet roundup of non-citizens

right after 9-11, where at least 662 were imprisoned for weeks and months

without charges. It was all racial profiling. It was very clear they were

looking for people who were Muslims and didn't look like what these people

thought were Americans. This has been going on and it continues to go

on and it is all so stupid in terms of investigation of actual possible

terrorists. What they have done by doing this, instead of getting people

in Muslim communities, who might be interested because this kind of Muslim

religion that has become crazed and lethal is not representative of what

most Muslims believe and many of them might be willing to help and find

out information, but they are afraid. They are afraid that because they're

Muslim, when they come and register, they wind up being clapped in prison

and maybe deported for minor violations of immigration law. Even William

Webster, the former head of the CIA and former head of the FBI and then

a judge, who is hardly soft on crime, has criticized Ashcroft for doing

this instead of old-fashioned legwork. There is Jose Padilla, who is now

being held as an enemy combatant with no access to lawyers. He was arrested

in Chicago on the allegation that he was plotting with al-Qaeda, working

on a dirty bomb. Instead of watching him as he came off a plane and following

him and seeing whom he contacted, they arrested him and here is John Ashcroft,

who was in Moscow at the time, announcing on television that they found

this terrible guy. To this day, they won't allow his lawyer to even see

him.

FJ: Is there really such a thing as free speech?

NAT

HENTOFF: Oh, we're doing it now, aren't we. As a matter of fact, Fred,

the American Civil Liberties Union, this has been the finest hour in its

history. They have certainly been exercising their free speech. The most

heartening thing that has gone on since 9-11 is the rise of Bill of Rights

defense committees. It started in North Hampton, Massachusetts in February

2002. A group of citizens: teachers, lawyers, students, retirees, social

workers got together and convinced the town council to pass a resolution

defending that city and town from the depredation of civil liberties,

instructing the local and state police to at least tell them when the

feds were coming in and doing what Ashcroft had pushed through in the

Patriot Act. There are now at least 146 cities and towns around the country

and I wish the press would pay more attention to this. Three state legislators:

Hawaii, Alaska, and Vermont have passed similar resolutions. As a result,

the Justice Department is getting a little apprehensive. A week ago, the

House of Representatives, it is the first time they have cut the funding

on a section of the Patriot Act, Section 214, which allows the FBI and

other law enforcement agencies to come into your home or office when you're

not there and not leave any word that they've been there for 90 days or

sometimes longer. That funding has been cut for that kind of search without

immediate or quick notice. There is resistance and there is certainly

plenty of free speech. I think people who start talking about how this

has become a totalitarian state are giving up. We have our speech. We

have our right to insist that Congress be accountable and keep the separation

of powers. That is what people are doing, so we are far from a totalitarian

state. The problem is where are the Democrats? Not one of the hordes of

people running for the Presidency have made an issue of what's happening

to civil liberties. When Ashcroft was pushing through the Patriot Act

and later, the executive orders, the Democratic leadership in Congress

was silent. Only one Senator voted against the Patriot Act and that was

Russ Feingold of Wisconsin. The night of the vote, on the floor, Tom Daschle,

the Democratic leader came down and called a meeting of the Democratic

Caucus and said to not vote for any of Russ Feingold's amendments and

that he wanted this bill to go through as it is. So this is bipartisan

lack of faith in why we are Americans.

FJ: You have been outspoken on journalistic responsibility. We live in

times where tabloid journalism feeds our hunger for gossip. Isn't slavery

in Sudan or famine in North Korea or a prisoner without due process like

a tree falling in the woods when Kobe Bryant is accused of sexual assault?

NAT

HENTOFF: There aren't enough reporters or assignment editors who care

about that, about the fact that Zimbabwe is being ruled by one of the

most vicious dictators in modern history, Robert Mugabe. Interestingly,

there is only one person I know of in the entire media who has as his

beat, the state of health of the Constitution and that is Judge Andrew

Napolitano, he used to be a judge in New Jersey and his statement and

his analysis on FOX News, which the left maligns all the time because

they don't listen to it. That is the only network that has somebody whose

beat is to tell people what is going on and he has been more critical

of Bush and Ashcroft on civil liberties than anyone else I know of. Nobody

pays attention because nobody thinks to listen to FOX News and yet, there

is this guy. We should have the equivalent of a Napolitano on every radio

and television station. Bush and Ashcroft, it's like a mantra, they are

saying that we're fighting to protect our liberties against terrorism,

but they are the ones who are invalidating the very liberties we are trying

to protect. The media should be much more alert on that.

FJ: What is the state of jazz today?

NAT

HENTOFF: Thelonious Monk was once asked that question and he said. "I

don't know. Nobody can tell you. It may be going to hell." That is

not the point. The point is there are plenty of musicians who are playing

beautifully and with great vigor. I went to hear Joe Wilder, who is eighty-two

years old now at the JVC Festival on the same bill as Frank Wess, who

is also eighty-two. I heard Clark Terry the other night. He is in his

eighties. Categories aside, there are young people coming up, Wycliffe

Gordon, who is a wonderful trombonist, who you can hear the whole history

of the trombone when he plays, including his own voice. The problem with

the state of jazz is not the musicians. It's the audience. The record

companies are very active in terms of reissues, which is fine. It doesn't

cost them much money. But it is hard for groups to get heard. While the

club scene is still OK is places like New York, there isn't enough work.

Public radio cut its jazz drastically. Public television, except for Ken

Burns' series has done practically nothing about jazz. The audience is

there and you can tell that by schools where there are more and more courses

on jazz, but in terms of public availability of jazz and hearing the music,

that is diminishing. Now, you've got these kids that think that it's all

free, They can rip off recordings and who cares about the royalties to

musicians, which are pretty low anyway.

FJ: So should we be in crisis mode?

NAT

HENTOFF: Oh, well, there have been ups and downs in the past. There will

always be musicians and people who want to hear them. People aren't getting

enough gigs, but it is not a crisis state. It is a state where the music

keeps alive. I don't go for the sky is falling. You just keep calling

attention to our liberties and to the exemplification of why we are Americans

and that is the spirit of jazz.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and is Wang Chunging tonight. Comments?

Email Him