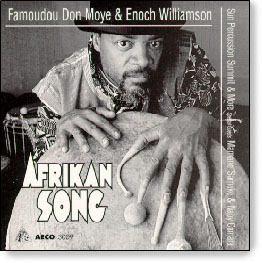

Courtesy of Famoudou Don Moye

Southport Records

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH FAMOUDOU DON MOYE

Don Moye was the last of the Art Ensemble to sit down with the Roadshow.

Was he ever worth the wait. But enough chit chat, here he is, unedited

and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

DON MOYE: I was in drum and bugle corps and church choir and my mother

used to manage and cook at a social club and there was a jazz club next

door. We lived up above that and so I met a lot of people there like Kenny

Burrell and Grant Green and Jimmy McGriff and Jack McDuff. Those were

the days of the organ. Every place of any repute, of any respectability

had at least a house band and an in-house Hammond organ, or a set of drums,

piano, or something, as opposed to jukeboxes now-a-days. My family was

all involved in the Elks Club. They had a marching band and they had little

combos and stuff. My uncles all played saxophone, although not professionally.

My father played drums in some of those groups. It was pretty much a musical

atmosphere. The music was around. My mother had a big influence on me,

in that she took us to see a lot of variety like in the summertime, they

had like opera under the stars. We would go see that or we might see the

Mormon Tabernacle Choir or go see Mahalia Jackson. Maybe it was natural.

I don't know if it was natural or not. I didn't just jump up and grab

a pair of sticks and go to work. It was just the environment was there

if I was willing to do the work, which fortunately, I had the sense of

discipline imposed on me at an early age with some of my teachers and

stuff.

FJ: Why percussion?

DON MOYE: Well, I started out in the drum and bugle corps and stuff. I

didn't really have an affinity for the bugle, blowing my brains out every

night trying to play a brass instrument and the drums, I just kind of

gravitated towards that. I had some violin lessons for a while too in

my later youth. I liked the violin. I was always attracted to strings,

the sounds and when I went to North Africa and started traveling around

to the Middle East and Japan and to other countries and cultures, I really

appreciated the training that I had. That was my choice to play violin

because I was attracted to the sounds of the strings. That more or less

enhanced the camaraderie that I have been able to maintain over the years

with bass players and string players and stuff. I didn't really go as

far as I would have liked to because I have got a special spot for strings.

FJ: Let's touch on your association with the AACM.

DON MOYE: I wasn't there in the beginning. I got to Chicago in 1971. I

met the Art Ensemble in Detroit, when I was going to school in Detroit

in '65. I met the Art Ensemble first because we had a place in Detroit

called the Artists Workshop and the people were around there like Marion

Brown and a trumpet player named Charles Moore. I lived in the same building

as Charles Moore and so he was more or less my mentor because I used to

go up there and he would be going over the changes to "Giant Steps." He

just kind of encouraged me to practice and I met a lot of professionals

coming by his house. Charles Moore kind of steered me into that direction

because I was more into, even at that time in school, I was a member of

the African Cultural Ensemble, which was composed a lot of students from

Kenya and East Africa and some people from Ghana and so we played a lot

of songs and rhythms from all these different countries and so I was focusing

on that. But at the same time, I was around Charles where all these drummers

were coming around and they had this organization called the Artists Workshop,

where people would be practicing all of the time. Marion Brown was around

there and they would bring in people for concerts. It was like a cooperative

of writers, painters, musicians, dancers and everything and the Art Ensemble

would come to Detroit and play concerts at the University and then they

would stay, there were these whole row of townhouses and they would stay

there and rehearse there for weeks at a time, so that is when I started

getting around that kind of music.

FJ: Let's talk about your association with the Art Ensemble.

DON MOYE: That was in Paris, late 1969, early '70. I had all of my stuff

at the American Center for Artists. The American Center had a big complex

there that would have rehearsal rooms, dance studios. They had a performance

space, so all us musicians would gravitate around there, like Art Taylor

and Johnny Griffin and Slide Hampton and all those guys, they used to

rehearse there. They would have concerts all the time and so that was

one of many places around Paris at that time where they would have concerts

on a regular basis, like almost every night of the week or some kind of

cultural activity, opening, painter's opening or dance recitals, classical

music, jazz concerts, African dance class, or all kinds of stuff. I met

them in that environment because I used to store my equipment there and

rehearse there. They would be there all the time. That would be the hangout

at day and then there would be concerts at night. You could make contacts.

It was kind of a networking area. I tell you what, Fred. I thought that

this is what it's all about. When I first saw them in '65, I said, "Whatever

this is, this is what it's all about." I was around their rehearsals you

see. In the early days, all the way up until recently, we used to rehearse

six, eight hours a day, everyday. So I would hear them rehearsing over

there and they would rehearse all kinds of stuff because Joseph or Roscoe

or Roscoe or Lester, whoever it was, the horn players would get up in

the morning and rehearse these classical pieces and all kinds of stuff.

In the rehearsals, they had a thing that they called the "Hot Twenty,"

where they would play twenty different songs everyday from all different

idioms. That was kind of a personal warm up that they called the "Hot

Twenty." It was just a variety of music that they were working on and

then it was an extended period of working on improvisations and personal,

original compositions and everything. That was my initial impression.

It was a vast repertoire of dealing with so many idioms and attempting

to play them correctly with the correctness that was required and the

necessary technique to do that.

FJ: Sounds like they were a good fit for you.

DON MOYE: Hell, no (laughing). It was a challenge because we were doing

all kinds of stuff, shuffles and Lester came out of that whole R&B circuit

and he was all about that stuff. He played with circus bands, R&B. His

greatest dream at that time was to go get in the trumpet section with

James Brown (laughing). I mean in the early Sixties, he was always going

to those auditions. He was always trying to get that trumpet gig with

James Brown (laughing). Anyway, he was around in St. Louis and all over

the place working that circuit with Oliver Sain and Little Milton and

all that. So there was a strong emphasis on that. And Favors had been

around that scene in Chicago with all the bebop cats. He came all the

way up through that, getting his ass kicked ever night in the "C" level

jam session and then you move up to the "B" level jam session and then

you move up to the big boy jam session. So he went through all of that

whole gauntlet. And then Roscoe and them, they came up around their stuff.

At that time, it was a lot more in the world of music in anybody's household

or even on the radio, there was a much more variety of stuff than there

is now. Everything now is programmed so tightly, you know, rigidly. One

idiom doesn't have any programming that would involve another idiom and

all that kind of shit. In those days, it was all kinds of music around,

in my house, I know that. It was a much more varied musical environment

in our homes and just in society in general.

FJ: It was that kind of variety spawned groups like the Art Ensemble,

do you fear that in this day of conformity groups that propel the music

forward will cease to exist?

DON MOYE: I just know that it's harder for younger musicians to go play

and go see other people play and just work on their stuff. There is no

real test area. For example, Fred, in New York, they have a jam session

that you have to pay to go to. That's been going on for a long time. There

used to be times where any town you go to, you play your gig and after

you're done there, you go out and find a jam session. This is really before

my time even. There were still quite a few places and jam session every

night, somewhere on a regular basis. I have been fortunate enough to travel

a lot and to a lot of different countries. I just noticed in the last

thirty years that any town: Berlin, London, Tokyo, Rome, there were even

jam sessions in those towns. That environment is not around anymore. Other

than the schools and the academia, there is really no place for young

cats to go learn how to play. They can learn about theory and technique

and all that, but they don't really have no place to go to put their shit

on the line and see how it works with all the people that are trying to

do the same thing.

FJ: The Art Ensemble certainly put it all on the line.

DON MOYE: I wasn't in the band when they go there (Europe). I was in Europe

already when they got there. But I knew that the reception when I got

to Europe, there was more work, more places to work. So functionally,

that was the reason why people would go to Europe. We went to Europe just

because there was more opportunities to work with the intention of coming

back. Now a lot of people, post-War phenomenon, people were leaving a

lot like Johnny Griffin, what's his name, Don Byas. They were in Europe.

They went to Europe and planned to stay there. That is where the ex-patriot

concept came from. I know when we went there, I went there with a group

that was already functional. When the Art Ensemble went over there, they

had a whole group, dogs, trucks, families, a couple of motorcycles, kids.

It was just employment opportunities, more chances to make a living playing

the music of our choice.

FJ: Lester's passing must have caught you off guard.

DON MOYE: Hell, no. I was there the day he got sick. As a matter of fact,

Fred, he got sick in Lisbon on my birthday a year ago in '99. The whole

band got sick, Brass Fantasy, because we went to a restaurant and got

food poisoning. I didn't get it because I was in another part of the restaurant.

But something that they ate at that table, and Lester, everybody else

recovered after two or three weeks and he hadn't recovered yet and so

he went in for some tests and that is when that came up. That was May

and he died in November. The onset of the illness was sudden, but his

march towards getting out of here, that last tour and everything, I made

the last tour with him for Brass Fantasy.

FJ: Do you miss him?

DON MOYE: I don't really miss Lester. He ain't here. That is a day to

day thing or a situation to situation thing because he done already made

his transition. The reality is that he is not there and as you get older,

you learn how to deal with that. It is not a continuous, continuous emotion

or sensation of loss or missing. It just comes up certain times when you

are doing stuff that inadvertently, you realize that that person is not

there.

FJ: Let's approach it from a more practical sense.

DON MOYE: It's more than a trumpet. It's his personality. Everybody always

tries to restrict that to a musical thing and we went through the same

thing when Joseph decided what he was going to do and not be in the band.

Adjustments can be made. Obviously, it is a void in terms of the harmonies

and melodies, there is a part that isn't being played, so musically, we

make an adjustment, but in terms of what we're playing, then you miss

the person's personality inside of the music, the personality and the

individuality that they lent to their part of the note. The Art Ensemble

was whoever we decided was going to be on the stage that day (laughing).

In terms of the business aspect, I spent many years and may times arguing

with people about what we were presenting against what they were expecting

or demanding. Is this a body count or are we dealing with the thing that

we are representing? Are you saying to just get a fifth person on stage

and you won't deduct any money? You don't pay no extra when we do a special

project and we bring special guests. The price don't go up. We just say

that every time we have four or five people, there should be a percentage

scale and we get more money and then if there is less, you know, on the

rational that they present. I just said that you've got to deal with the

music. This is the Art Ensemble as is. Take it or leave it. If we decide

to have a special guest and not a replacement, then we will deal with

that. You get the full show. You get the full thing, everything we agreed

to contractually. You will be fulfilled aesthetically and everything.

If you want to start making comparisons, that is not my problem. We made

tours when Roscoe got sick. We made tours with me and Lester and Malachi.

I got a tape of a concert that we did up there in Seattle and we played

a one and a half hour concert. We have been playing long enough that we

know how to act like we're playing when somebody ain't there to pretend

like they are there. That is the problem with a lot of bands that a lot

of people are trying to fulfill the listeners expectations. Why don't

you deal with what is happening, not what isn't happening or what you

want to be happening? Like one time I played a gig with a band, we ended

up playing together for a while. It was another cooperative band and the

bass player had another gig Uptown and the piano player was trying to

play as if the bass player was there. After a couple of tunes, we just

stopped and I said, "Look, you should be playing like the bass player

isn't there. Don't try to cover for the bass. Deal with what you're doing.

There is not a bass player here. You have got to be playing with who is

there. Make something out of that." We don't have a fixed program. Don't

try to cover and make the bass player be there when he isn't. That is

an opportunity to make something happen and investigate other nuances,

other things, the subtleties in music.

FJ: So am I to assume that the Art Ensemble will be recording as a trio?

DON MOYE: Yeah, we have done some recordings in the can already. We are

working on mixing them now and grinding out the contract and going through

this business deal. We have got stuff on our own label and we have got

stuff on the Birdology label, which is the same label, it is Birdology

out of France. It is distributed by Atlantic in the States. The next thing

is going to be called Art Ensembles of Africa. We just finished that project.

That was in the spring. I have been in the process of going back and forth

to Paris to mix that stuff. It is like a nineteen piece band. Yup. And

we have got a couple of trio things that we have got in the can and we

just have to decide whether we want to do a live record or go back into

the studio. There is a lot of stuff. We have got historical stuff. We

have got a couple of hundred tapes sitting around and so we have got plenty

to do. We are trying to make it to the finish line, Fred, and go relax

under a palm tree somewhere.

FJ: If there is justice in this world, that palm tree will be coming real

soon.

DON MOYE: Thank you, Fred.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and is not on the Vietnam Memorial.

Comments? Email

Fred.