Courtesy

of Ellis Marsalis

Columbia Records

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH ELLIS MARSALIS

As the father of four established musicians, Branford, Wynton, Delfeayo,

and Jason, Ellis Marsalis must sleep like a baby at night. Such astounding

musical wealth from one family is still quite difficult for my pea brain

to comprehend, but I am just a simpleton. I spoke will the elder Marsalis

from his home in New Orleans about his musical life, his children, and

the future as he sees it. It is a candid conversation, unedited and in

his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

ELLIS MARSALIS: When I was about eleven, my mother bought me a clarinet.

I played the clarinet through most of high school and eventually, I got

a tenor saxophone, which was around '48, '49, something like that. I started

trying to learn these rhythm and blues solos and was pretty successful

at doing that. By the time, just before I got out of high school, we,

a group of us formed this band that used to play for school dances and

I was playing tenor saxophone. When I got out of high school, I went to

a local university as a music major. I was still, to some extent, playing

clarinet. However, this university was not a really strong music school.

When I say strong, what I mean is there was no orchestra there. So essentially,

I wasn't too keen on playing traditional jazz, so the clarinet sort of

fell into disfavor. I had studied some piano and more and more people

would call me when all the good piano players who were in town were working,

they would call me to come and play on different kinds of jobs, mostly

like rhythm and blues jobs. Eventually, I started saying, "Hum, there

is some work to be had here." And so I started to concentrate a lot more

seriously on piano. By the time I got out of college, I was bitten by

the jazz bug, which wasn't a good thing for making money. I started working

at trying to become a better jazz player and I have been doing that ever

since.

FJ: What was your first paying gig?

ELLIS MARSALIS: Oh, yeah (laughing). I can remember, the first paying

gig was in high school and it wasn't even supposed to be a paying gig.

A group of us in high school, the piano player in the group, his music

teacher had a party for her students at the end of the year and asked

if he could get a band. So he said, "Yeah, I'll bring my band." So we

went to the YWCA in New Orleans and he had told us that we were going

to play and that it was not a paying gig. We were just starting out anyways,

so we said, "Yeah, OK." So we went and we played and they really liked

us, so what they did was they passed a hat and we made a dollar and a

half a piece (laughing). That was the first time I remember actually getting

paid for a job. Not long after that, we thought about it, "Man these people

were willing to pass the hat for us, maybe we can make some money." So

we started playing school dances after that. We went to at least five

dollars a piece. It went pretty much from there.

FJ: As an

educator, a piano player, and a composer, is there one aspect that strikes

a chord above another?

ELLIS MARSALIS: It's really hard to say, Fred. I don't foresee the day

when I won't be a teacher. I can foresee the day when I may not be employed

by an academic institution, but I think that I will always, in some form

or fashion, be a teacher. As far as playing is concerned, I enjoy playing,

period. I just enjoy playing. I don't work at it now, probably as much

as I should. My composition is another thing. I have mixed feelings about

that. I write some tunes every now and then, but I don't necessarily consider

that composition. I don't know if I will really sustain an interest and

go more into composition once I retire from the University (University

of New Orleans). I don't know.

FJ: As an educator, you have been a teacher to some of the music's celebrities,

Terence Blanchard, Nicholas Payton, and Harry Connick, Jr., is there one

student that stands out in your mind?

ELLIS MARSALIS: The one student that comes to mind and I don't know if

it would be correct to say that there was some humongous obstacle that

he had to overcome, but he did put some concepts of playing the instrument

together in the shortest period of time that I've ever known anybody to

do and that's Reginald Veal, the bass player. When I met Reginald, Reginald

was in junior high and I didn't actually get to interact with him as a

teacher until he was I think either a senior or a junior in high school.

He was an electric bass player and he used to play with his father's gospel

group and they would tour around. When he took the audition at the high

school that I was teaching at, and he got in, it was obvious that he was

talented, there was no doubt about that, but he didn't have any experience

with jazz. So I started working with him when he graduated and eventually

over the summer in Baton Rouge, and I was able to convince him to get

an acoustic bass and we started working with that. Somewhere around 1984,

I got a job at a club here and I needed a bass player because the bass

player, who was also another former student, was working and couldn't

make it. So I asked Reginald, who was at Southern University at the time,

if he could come in on Saturdays and make this job. Well, he hadn't really

been playing acoustic bass that much. In fact, I don't even know if he

owned one. But he agreed to come in and I said, "Look, we'll play whatever

is comfortable to your technical abilities, rather than try to force anything."

I hooked him up with the associate principal with the New York Philharmonic

for lessons. He was an extremely diligent student. He practiced consistently

all the time and in two years, he had put it together. We went on an Asian

tour in '86 in June, I think, May or June and when we came back from that

tour, I had accepted a job in Virginia, at the Virginia Commonwealth University

and Reginald packed his stuff and joined Terence Blanchard's band and

that was it. He hasn't looked back since. I had never seen or heard of

anybody who had put the concept of that instrument together as rapidly

as he did it. That is not an easy instrument to play, not that any of

them really are, but to really be a rhythm section player, because that's

like the mule team of a band. As a bass player, you have really got to

have a lot put together to go after two years and jump on the professional

scene with somebody, especially like Terence. He stayed for a long time

with Wynton's band.

FJ: As the patriarch to the music's most prominent dynasty, you must beam

with pride at the success of your sons, Branford, Wynton, Delfeayo, and

Jason.

ELLIS MARSALIS: They were also students at the high school that I taught

at, so I was able to see them from both sides as parent and also as teacher

and I always felt that what they did, essentially, was what they were

formally trained to do. I've seen a lot of students who had tremendous

talent, but they didn't work or if they did work, they allowed other things

to interfere with what would be needed to elevate themselves on a much

higher plain than just a local musician with some talent. So when I think

about them, I think about the fact that they're basically doing what they

were trained to do. I don't really think that talent is any kind of mystic.

It's definitely a gift. Some people say it's a gift from God, depending

on what religion you profess. I don't have any reason to doubt that, but

when it comes right down to it, I've seen too many kids with too much

talent that never went anywhere. So I'm more inclined to think that the

thing that they did was ninety percent work. As far as me being proud

of them, well, yeah, but I'm just as proud of my sons who don't play music

at all.

FJ: Have you been approached by some clever A&R person to do a quintet

recording with Wynton, Branford, Delfeayo, and Jason?

ELLIS MARSALIS:

We always get stuff like, "When are you all going to do a family album?"

We get that so much that I've lost count. I've never wanted that. I'm

now looking back in retrospect, that might not have been correct. Maybe

it would have been a good idea if we would have had that. I never really

wanted that. I never did feel comfortable with the idea of a family band.

I always felt that if it was a family band, essentially, it would be my

band and that would have a tendency to stifle the growth of the younger

people. My youngest son played with me for five years. We quit the trio

last October to go do some other things and to me, that's what it's all

about. I think the problems come, when families have bands is that the

economic substance of family becomes tied to that and when somebody wants

to depart to go do their own thing, it causes a lot of problems. I never

really had economic notions about a family band.

FJ: Louis Armstrong once pointed out that, "Musicians don't retire, they

stop when there's no more music in them." Do you believe that there is

a point in a musician's life when there will simply be no more music in

them?

ELLIS MARSALIS: Well, most of that, I don't think that has to do with

whether there is music left, I think it was Duke that said, "You're just

playing the same song all through the years, but he just did it in different

ways." I think what happens is that we lose a certain amount of interest,

which causes us to de-emphasize what we've become known for doing. In

some areas, it has been very difficult to grow beyond a certain level.

Among some of the greater composers that came out of Europe, there wasn't

but one of them who was kicking butt until he died and that was Beethoven.

The rest of them, except the ones who died real young, like Mozart was

thirty-six, and you get a jazz musician like Charlie Parker who was thirty-five

when he died. I don't doubt that as young as Coltrane was, I don't know

that Coltrane had much more that he was going to say in the form that

he was functioning in. Yusef Lateef is writing for orchestras now. Wynton

is working on a piece for the New York Phil right now. I had told him

years ago, I said, "Man, at some point, the only place for you to go is

composition." There is not an endless cycle of growth that takes place

with any of that. There's people who are writers. How many books do people

really have? You look at a William Shakespeare and that's why a lot of

people don't believe that it was one person. For the most part, we either

lose interest, which in another way, it could be considered as running

out because there is definitely a way, in composition it's called repeating

yourself or imitating yourself. I think there's a certain way you have

to live which would permit someone who grows into old age to continue

their growth cycle. I don't think it's impossible because Beethoven lived

to be sixty or sixty-five and was growing all the time. That to me is

amazing. It really is amazing to listen to that music and hear the growth

in the middle to the late string quartets, from the first to the ninth

symphony too. Man, none of the rest of them were like that. Haydn wasn't

like that. He had a hundred and six, but you can pick three of them and

there it is.

FJ: You alluded to Wynton writing for a symphony, he has released an enormous

volume of material this year by anyone's standards and in doing so has

met with great criticism that he maybe putting too much at one given time,

and thus diluting his musical output for the future.

ELLIS MARSALIS: Actually, Fred, I think that is stupid. What does putting

these recordings out have to do with his ability? I don't even understand

that. When people write things like that, it doesn't sound to me like

an intelligent statement, written by anybody who understands any kind

of music. When you are in this kind of business, the business part of

it, let's put it that way, the only thing that you really have is a way

to put out material that has to do with whatever you are about musically,

I mean, Jimi Hendrix did that. Jimi Hendrix had so much music they are

still putting out stuff that they find. Miles put out a ton of stuff.

That's the record company's thing. The record company wants you to put

out one record and sell it until they can't sell it no more, which is

about a year and then go out and tour and do all this stuff and then come

back and do another record the next year. That has nothing to do with

anybody's talent or ability. That's somebody else's business approach.

I don't know what kind of music writer they are.

FJ: You mentioned Beethoven's body of work. Many Europeans and some artists

in the States feel as though jazz, in all its forms, is America's classical

music. Is it?

ELLIS MARSALIS: No, I don't like the term. I never did. The mere fact

of referring to jazz as anybody's classical music is essentially borrowing

a term which describes another culture's excellence and sticking it on

this culture's excellence without doing whatever the homework is to develop

the vocabulary to adequately describe what actually takes place with an

Ellington. You see, Fred, Duke Ellington made a community and he wrote

music for that community, that community of musicians. He exploited, and

when I say exploited, I'm not talking negative, he explored and exploited

the abilities of everybody in that band. They were different people at

different times, but that band had a nucleus of people and he wrote for

that band. Beethoven wrote for Beethoven and everything that he wrote

was the sentences of one man. In fact, he even made a statement when he

sent a violin concerto to a guy and the guy said to him, "This is unplayable."

And Beethoven said, "I hope you don't think I was considering your meager

talents when I wrote this music." He wrote music for a keyboard, which

was not even in existence at the time. This is the sentences of one man.

He wasn't dependent upon the musicians around him to give him any inspiration

that was really needed to be the composer that he was to become. If he

would have, that would have been sad because they were so far beneath

him, it wasn't even funny. Ellington's whole process, Duke was an artist.

He was a visual artist and I think that what he did is similar to what

sculpture does. His pieces came out of, he almost sculpted these pieces.

They came out of what he heard the musicians play and formulated pieces

and developed a whole sonic language out of that. When you really listen

to Duke's band over an extended period of time, what Duke did with the

riff was something that none of the other musicians did. Charlie Parker

did a tremendous amount with the riff and so did Dizzy. They wrote themes

off of that, but harmonically, most of them were just standards. Compositionally,

the harmony was simple, very basic.

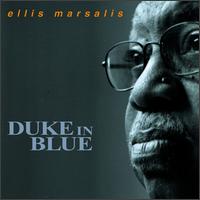

FJ: Let's talk about your latest release, Duke in Blue and Ellington's

influence upon you.

ELLIS MARSALIS: Duke Ellington's music really didn't have a big impact

on me. I used to go and hear Duke back in the fifties, middle fifties,

because Duke used to do these Southern tours and he would come through

New Orleans. We used to Booker Washington Auditorium, which was the only

place that black people could go anyway to hear musicians that came into

town. I didn't really know who Duke Ellington was. I had a cursory awareness

of Duke Ellington. I wasn't that much of a musician. I was still learning,

but I knew that the band was still swinging. Eventually, I did play some

of Duke's pieces, which melodically was very challenging, songs like "Sophisticated

Lady," which is very challenging. "Prelude to a Kiss," which was melodically

and when I say melodically, I mean singable. We grew up as a whole people

hearing music that was singable like "Jingle Bells" or "God Bless America,"

which were structured in a way that they are singable by just the average

person. You don't need to be a vocal specialist to sing them. And Duke's

music had that quality in terms of the melody, the way that his melody

was constructed. One of the reasons why I think people didn't like Monk

was because Monk's musical logic took on different proportions than a

lot of other people. Monk was very much influenced by Duke Ellington.

My primary influence, instrumentally was Oscar Peterson, musically, it

was probably Bird, Charlie Parker. This record was recorded at the University

of New Orleans. I was kind of surprised. I don't usually like what I do

after I finish it. I listen to it and put it on the side somewhere and

don't listen to it. I was a little surprised. It sounded better than I

thought it would. By the time I had heard it, I had been away from it

for so long, I could bring an objective ear to it. In fact, I just got

a shipment from the record company last week. I had to call them up and

say, "Man, the record is out. I went to Canada and somebody had it and

I haven't gotten one yet." I was pleasantly surprised because usually

you hear something and you say, "I wish I could have done this one again."

FJ: Do you see a prosperous future for the music in the next century?

ELLIS MARSALIS: You see, Fred, the thing that kept the music from spreading,

essentially, was the racism in America. When I was growing up, the bass

player that I am working with right now, he is about a year, maybe two

years younger than me, and when we first met, we couldn't even play on

the bandstand together. We couldn't even sit down and hold a conversation

anywhere. So if there had not been all this racial segregation, who knows

where the music would really be now. I don't know. This music is created

in a very democratic environment. That is to say, everybody who is a part

of a group, is a contributing element to the total success of the end

product, unlike a symphony orchestra, where the total success there is

a sound. The music has already been written by somebody many years ago

and it doesn't matter which orchestra you hear play it, the notes will

never change. But the sound will change depending upon the individuals

in that particular orchestra. But with a jazz band, you can find fifty

different bands playing fifty different ways. I think invariably, I think

it just depends on what kind of composers come out of the mix. Jazz musicians

are like conversationalists. Once you finish a composition, it's up in

the air. I was thinking about this piece, "The Christmas Song." There

was an interview with the composer, who passed away not too long ago.

FJ: Mel Torme.

ELLIS MARSALIS: Right, Mel Torme. It was like in the middle of July on

a hot day and it took them fifteen minutes. The extent to which the improvisatory

element remains will largely depend on this country. There are things

about this country that seem to be going away from that, from that improvisatory

element. I don't think anybody looks at it like that. During the second

World War, one of the things that enabled us to defeat the Germans is

they couldn't improvise. A good percentage of the leadership was dead

at the officer rank and so when the German senior officers were killed,

they surrendered. Them cats were surrendering to news reporters and photographers.

They couldn't improvise. They didn't know what to do. Invariably, if people

don't have a lot of respect for improvisation, that's another reason why

the powers that be were against jazz. They wanted somebody to write it

all down and organize it and print it all out. Not that there is anything

wrong with that, but when it comes down to it, this country is about improvisation,

some positive, some negative. I would imagine, Fred, that if there is

ever going to be an American music, jazz would be the cornerstone.

Fred Jung is Editor-In-Chief and can't believe jazz is failing when there

are about two billion summer festivals. Comments? Email

him.