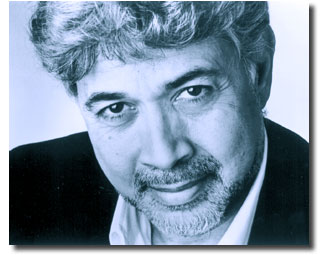

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH MONTY ALEXANDER

I have

been known to light up a cigar every now and then. An Ashton VSG, 25-year-old

Macallan (sinfully on the rocks), a warm fire, a comfortable leather chair,

the soothing sounds of Sinatra, and I am indeed in heaven. So when I received

Monty Alexander's new My America record that features "Summer Wind,"

a Sinatra staple, I was a bit skeptical. After all, I knew Alexander from

his Bob Marley material (which an old high school teacher of mine took

to play in his class and never returned). I was surprised at Alexander's

rendition of Sinatra. It proved to me that he was no one trick musician

and I explored his other material. Impressive. What I didn't know was

Alexander had ties to Sinatra and this I learned during our conversation,

amongst other things, as always unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

MONTY

ALEXANDER: As a young fella in my hometown of Kingston, Jamaica, I experienced

the joy from five years old, when I heard musicians play and I had records

in the house. My parents had music, including popular music and Broadway

songs and cowboy songs and calypso and I heard Louis Armstrong. We had

Nat King Cole as a staple. And so I heard all this music and I loved it.

There was a piano in the house and I gravitated towards the instrument

playing my own songs on it, picking it up as a kid. It's a typical growth

pattern for a lot of young people. I was just automatically inclined to

be a music person. It stuck with me and I was told to go to a piano teacher,

which I did just for a few years. Throughout all that time, it wasn't

the piano lessons that made a difference. It was my own personal instincts

that attracted me to see musicians play. I have a lot of memories of folk,

calypso bands around in Kingston, Jamaica and I would go hangout with

them and watch them play. I had an accordion and I would go sit in and

play. So from an early age, the joys of sharing music with other musicians,

but it was Louis Armstrong that I saw in Jamaica that really grabbed me.

Boy, I saw this guy on his trumpet and that was it. I was about nine or

ten years old when I saw Satchmo. My dad gave me a trumpet the next day

and I tried to play the trumpet, but I couldn't find how to play the trumpet

so well, but I loved the feeling of this music. It was the man, this jovial,

positive, funny, entertaining, happy guy, who made this sound on the trumpet

that was so pure and beautiful. Of course, we heard him singing those

notes with his gravely voice. The whole thing and how the people got caught

up in the feeling of the music. So it is just what happens when jazz takes

off and it infects and gets into people and the next thing you know everyone

is having this great feeling so that music can do that to people and make

them feel so happy as well as, that is just it, the spirit of the event

and that is what grabbed me. Of course, I thought he was just this incredible

guy with such a beautiful personality and everybody smiled when they saw

him. That stuck with me because musicians that I saw after that, musicians

that included your character. Nat King Cole had a way of being gracious,

who I also saw in Jamaica. It was all about literally making you feel

good and I wanted to make people feel good as well as myself.

FJ: Audience involvement is more often associated with Latin jazz and

not the jazz of Miles Davis, who was infamous for turning his back to

the crowd.

MONTY

ALEXANDER: That is my natural tendency as a person with music. I guess

if I tried to analyze it, I'm so grateful that I have this opportunity

to make music and I just love every note I play unless I'm having a terrible,

terrible, bad day, every note I play is a moment to rejoice that I'm alive

and that's how I feel. I dig Miles Davis very much. I knew the man and

I was fascinated with his whole mysterious kind of thing and I think he

was just a very, very complex guy, who when he played his music, it was

fascinating and you felt the talent and the genius of the man, but it

was not his nature to smile with you. It was a very brutish kind of personality

and I'm just going along with my personality. My personality is one that

is more, I don't have problems smiling with people and that's what I do

with music. I want to smile.

FJ: How did you go from local Jamaican musician to playing with venerable

jazz musicians on the mainland?

MONTY

ALEXANDER: I first came to America to live. I was just turning eighteen

years old. I went to Miami, Florida, family circumstances. My mother decided

that we were going to go to Florida. So I said, "Yeah, let's go."

I loved it. I was going to land of tall buildings and where all these

great artists came from. I had already been around Kingston playing in

the nightclubs and hanging out. I shouldn't have been doing that. I should

have been in school studying, but I was hanging out with the musicians

having a ball. I was in my early teens and I was also going to the recording

studio in what was the beginning of that whole scene in Jamaica, what

became the great popular music that brought Bob Marley. When I came to

Miami, I immediately started finding the musicians, the local guys and

hanging out with them and just going up there and be friendly and one

day I was invited to sit in, in a club that was right there on Miami Beach

and this guy, African American musicians who were very friendly towards

me, the next thing you know, I was sitting there, swinging hard with the

rest of these guys that were playing jazz, very kind of rhythm and blues-ish

and I got hired. Somebody saw me playing and I started getting bookings

around Miami and it was just a simple, natural transition. The next thing

you know, I was getting paid. I didn't go to school. I didn't plan on

having a career. I didn't think it was possible, Fred. How can I come

from Jamaica, this guy who just got here as a kid, how am I even going

to be lucky enough to get a job and the next thing I know I was working

around Miami playing in the clubs, playing in places where a lot of gangsters

hung out. I worked in those bars with the hookers. I was in Miami where

mostly white folks would be. I was also in Miami where mostly Black folks

would be and I was accepted by everybody because I come from a place called

Jamaica. We're not into that stuff. At least not back then. I was instantly

a professional musician. I was playing in front of people and I was just

seventeen, eighteen years old. It was just amazing and I've been doing

ever since.

FJ: Let's touch on your relationship with the late Milt Jackson.

MONTY

ALEXANDER: First time I met Milt was because I had a job playing at Jilly's,

a club in New York, where Frank Sinatra used to come a lot. This is in

the early Sixties and it happened because when I was playing one of those

bars in Miami, Sinatra and some friends came in and I got hired. It's

a short story and I came to New York. When I was playing at Jilly's, I

happened to have met these two musicians in Miami, who I called up when

I came to New York and the bass player was Bob Cranshaw and the drummer

was Mickey Roker. They were friends, good friends with each other. I had

met them in Florida. I didn't know it, but they also were working with

a lot of other people including Milt Jackson. One night, Milt Jackson

came into see them because they said, "Hey, Milt you have to come

here and see this little guy playing the piano." Milt came in and

he sat at the bar because it really wasn't his environment because a lot

of show business people were there, a lot of entertainers from Hollywood

and that scene, not so much the hip cats from the jazz world, even though

Errol Garner would drop in and Count Basie would drop in, all kinds of

folk, Miles used to come in there and hang out. I met Milt and he had

a skeptical look and not long after that, I also met Ray Brown, who we

are now sadly missing from his recent departure. But Ray and Milt got

together and I met Ray through the greatest accident and he heard me play.

He hired me to come work with him and Milt and that was in '69. I worked

with Milt off and on, recording a lot of records with him and Ray Brown

and that was some of the greatest associations I had in the jazz world.

FJ: Pigeonholed into calypso and reggae, people forget you play some mean

bebop.

MONTY

ALEXANDER: I played it then and thank goodness, I still play it when I

want, Fred. And I'm happy to make records that I enjoy making because

that's a part of my makeup. One of the things that I did as a young musician

was to provide music that made people want to dance. I love to see people

dance. Of course, the big beat was a part of that whole thing in Jamaica.

You crank up the electric bass, fat, low bass tones and that is something

that I dig very, very much, but no more or less than I also like to hear

other great men of virtuositic artistry, whether it's Art Tatum. It is

a part of me. It is the same way, if I can make a comparison to the way

that Ellington played. There were times when he played strictly for dance

and it wasn't a matter of it's instrumental, it's great artistry. It was

just we have got to play for dancing. I was invited by Telarc to make

records that tap into my Jamaican experience and heritage. That is really

easy and I'm happy to do it. It's my culture and I do it with Jamaicans

who really do it the best. That has not at all to do with when I go play

with the great jazz men. I'm still accepted happily by them and I love

to play straight ahead. You can say the records are just a part of it.

FJ: Neat records, Stir It Up: The Music of Bob Marley.

MONTY

ALEXANDER: Thank you. The way I approach music, I go for the feeling really.

I'm not much of a music reader. I didn't go to music school. I don't think

theoretically. I just kind of, on this occasion, aligned myself with friends

of mine who also loved and breathed what Bob Marley was about. I also

am a fan. I'm a big admirer and appreciator of the greatness of Bob Marley,

not only with the music that he played and wrote and sang, but the man

as a great human being and what he means to people all over the world.

The combination of my appreciation and value for what he is as a man and

his source of information, which is the Bible for most of it, and a lot

of the guys that I invited on this record, like I said, friends of mine

who also felt that way. When we got to making the music, when I would

play those notes, I wasn't just playing the notes on the piano, I was

playing Bob Marley and his philosophy and his songs and his hearts and

his message. It came out like that, that it wasn't just music. It was

almost a spiritual experience because Marley as you know, touched people

all over the world. It was just a matter of making the piano sing and

speak, whereas there were moments where I do what you call improvising

and I take it over in a little different direction, but I was doing my

best to honor the spirit of what Bob was all about and somehow it came

out pretty good.

FJ: The mainland may not be familiar with Robbie Shakespeare and Sly Dunbar

(Monty Meets Sly and Robbie).

MONTY

ALEXANDER: Sly and Robbie have made themselves a commodity, in that they

took what they did when they played live and they learned the magic of

the recording studio and because they are homegrown, down home, Jamaican

brothers, who revere in their heritage and love the old time Jamaican

rhythm, the mental music and the combination of rhythm and blues and they

are true alchemists. These men taped all that powerful rhythm that comes

from Jamaica. They have been able to go into the studio and make it one

voice, so much so that they've created an aura for themselves. People

all over the world know who Sly and Robbie are. They have to be, the kings

of rhythm because they live and breathe it. Sly almost sleeps in a recording

studio. But it is because he is a master musician and he just loves rhythm.

I do too, so it was just a natural thing. I met them years ago and they

suggested that we should do something and when the opportunity came, I

followed through and I'm proud of that because I really enjoyed the work

and I would say Sly and Robbie is like listening to a jazz rhythm section

because it's a whole world of what rhythm is all about, Africa and rhythm.

But there is something about Jamaica that sets us apart from anywhere

else. Gosh, that was a long explanation, Fred.

FJ: And My America, your latest on Telarc. Obvious references to 9-11.

MONTY

ALEXANDER: Well, the tunes, the original idea, as you probably realize,

every time these days you make a record, you've got to have a theme or

reason and we were thinking about what is something that sets each of

us apart because of my, assume, versatility, my sense of variety and I

come from another country and I tapped into this music given to us by

all these great men, not just jazz men, but pop music, Al Green and Marvin

Gaye, who were also very much loved. It was just to make a record that

was Monty Alexander, this guy from another country and this is why I love

America. The original idea was my America and we're planning this thing

and the terrible atrocity of 9-11 comes along and we can't make this record

now because it is too sensitive and not only that, people will say that

I am tapping into that bad experience. I guess you say to yourself that

no, that is the very reason why I can feel some sense of appreciation

for coming to this great country. I put those songs together to share,

why, but to make it a light hearted thing where people can dance and I

invited my Jamaican friends and we did versions of all these artists because

those are my favorites. If you noticed, Fred, I started off with one of

my heroes as a kid, Roy Rogers, because that is the first thing I learned

coming from America that grabbed me as a six, seven year old kid sitting

in the movie theater watching these men sing cowboy songs. That was the

beginning of it. Because of the atrocity and because I believe certain

things, I wanted to close the record with a statement that brings God

into the whole mix because that's a big part of what we are and I wanted

to celebrate that. There is a song in there called "The River Rolls

On," which is written by a friend of mine and myself and it is sort

of a statement that says that no matter what happens to us, we've got

to get up and keep moving. So that is what that record is about. It comes

with inspiration and gratitude.

FJ: What is your America?

MONTY

ALEXANDER: Well, everybody has a version of America. My version of America

is a land where all things are possible. But you have got to think for

yourself and you've got to grab opportunity, but at the same time, you've

got to do it where you're fair to one another. This land at its best represents

the opportunity that anything can happen. Even a cook can make it. This

is the land of opportunity and I really believe in the principles of freedom

and adventure. This is a place where anything can happen. You just have

to circumvent the cynics, which exist.

FJ: What is your Jamaica?

MONTY

ALEXANDER: Jamaica has gone through some growing pains and is still growing

through some growing pains. The Jamaica I remember and maybe naively so

was this incredible, beautiful Shangri La. It's like paradise really.

What I remember as Jamaica was the people and the warm hearts of the people

and the natural beauty of the land and the music and the culture and I

unfortunately, I have to make sure that I live in the present tense because

now we are struggling with a lot of things, social change and my Jamaica

is in transition for better days, but the struggle is on. Bob Marley sang

about it very well. But I dream of a time when the fears will go away,

in both Jamaica and America.

FJ: What is the biggest misconception of Jamaica and its people?

MONTY

ALEXANDER: That's a good one. From what I perceive, a lot of people, they

go there and Jamaica is not all reggae music. Jamaica is a multi-ethnic,

religious community of people who have been getting along with each other

very well over the years and things are a little stretched right now,

but I think people think Jamaica is Bob Marley or they think Jamaica is

Harry Belafonte or they think it's a rum and coke. Like everything else,

you can have a misconception, but I believe that because reggae became

so popular that they think everything is that and there is much more to

it than that. The Rastafarian movement is such a great movement, but there

is much more to it than that. The only was I guess is for people to go

there and meet the people, go up in the country and learn about it. I

for one, I love the older things, kind of like the music and culture of

America. It is the same with Jamaica. We have great culture that is about

people loving one another and getting along. It is something that I lament.

Elections are coming up and I hope people look at the bright side of things.

There is always too many elements of fear and despair that come in there

and cause problems. The world is in a challenging phase right now, so

we have to be positive. Musicians can help the world be a better place.

FJ: Nice you're doing your part.

MONTY

ALEXANDER: Thanks, brother.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and is one of major league baseball's

most memorable moments. Comments? Email

Him