photo by Marc PoKempner

Wobbly Rail

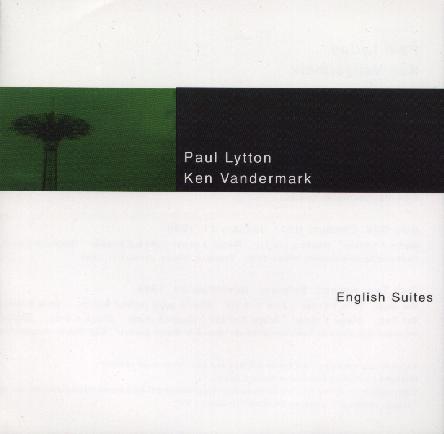

Atavistic

Delmark Records

A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH KEN VANDERMARK

There

are leaders and there are followers. There are those that fight the good

fight in the arena and then there are those who are content to be merely

spectators. I can’t imagine Ken Vandermark was ever a follower or

likely to be a spectator. After speaking to Vandermark on numerous occasions,

I have come away impressed by his sheer determination to create music

that is original, creative and beyond the traditional descriptions of

jazz writers. Perhaps that is the reason why when writers speak of Vandermark,

they take the easy way out and the first thing that they associate him

with are Eric Dolphy and his crew cut. Neither of those things have anything

to do with Vandermark and the grounds that he is hell bent on breaking

now and tomorrow. It is my pleasure to present an encore Fireside with

Vandermark as he sat down with the Roadshow after a lengthy tour. And

just so I have a clue, who let the dogs out?

FRED JUNG: With the number of recordings you have appeared on in the past

year, aren’t you concerned about overexposure?

KEN VANDERMARK: No, I’m not worried about it because I think the

perspective that people have on what I’m trying to do who feel that

way completely misunderstand what I’m trying to do musically and

the nature of the kind of music that I’m playing. If you want to

take models based on what I do, in terms of looking at history, look at

the kinds of recordings of say, not to put myself in the same musical

position as someone as Coleman Hawkins, in terms of importance, but I

build my work ethic on the stuff that he was doing in the Forties, with

performances and recordings. Look at the number of recordings a guy like

that is making. He’s in the studio playing with different people.

He’s working with the new bebop players. He’s recording with

people that are his peers that came up as the same time as him, guys like

Roy Eldridge or Dizzy Gillespie. He was in the studio all the time doing

stuff and performing all the time. I think the thing about the music that

I play is based on a process of development through improvisation and

the recordings are just indications of different things that are happening.

They’re not ends. They’re stepping points in a process. Considering

the different kinds of music of interest that I’m working with and

the different kinds of players I’m interested in working with, I

could see to an extent that there are a lot of records coming out this

year with my name on them. But I think if you take each individual recording

and look at what it is and compare it to the other things that are happening

and compare it to the other things that I have done, from my standpoint,

they are all radically different. So I feel like a recording with Paul

Lytton is radically different than a recording with The Vandermark 5,

which is radically different than a recording with Peter Brotzmann. So

if people who feel that I’m overexposed have a problem with the number

of recordings that are coming out, they just don’t understand at

all what I’m trying to do and that’s fine. But I don’t

think that they really perceive what improvised music is about. I would

argue that what is the right number of records to put out a year? What’s

the right number of concerts to do a year? How much is possible? And if

you think that only one record is permissible per year and it could possibly

be good, why one? Why not none? It is like perceiving recording, whether

it is a live recording or studio recording, recording as the goal and

recordings aren’t the goal as far as I’m concerned. Recordings

are indications of what’s happening and if you think it is too many

records, don’t buy them. A record costs, with the labels I work with,

twelve to fifteen bucks and how many movies do you see a year? How many

meals do you eat a year? I think that complaint is a misunderstanding

of what I’m trying to do.

FJ: What is it that you are trying to do?

KEN VANDERMARK: I’m really curious. I’m very interested in what’s

possible to do with the music and the history of music and so my whole

thing is to try to pursue as many avenues as possible, to work with as

many different people as possible, to play as often as possible, and to

find out what’s out there and what’s potentially in me to hopefully

contribute to the music that’s going on now. I’m just trying

to examine what’s happened and try to apply whatever knowledge or

understanding of what’s happened to what may happen or what may come

up. That’s why I’m interested in playing with as many different

kinds of people as possible. If you look at the people that I’ve

worked with and who I hopefully with continue to work with, you have a

range of people from people in the generation of Fred Anderson and Robert

Barry, who are nearly seventy, to the generation of Peter Brotzmann or

Paul Lytton, European players, American players, unfortunately, I haven’t

really worked with any Japanese players or people from Asia. There are

so many things to possibly do that the way that I learn is by directly

working with individuals whose work I like and learning from that process.

I guess, in terms of a goal, it’s just to continue doing those things.

What do you get out of playing with Misha Mengelberg? What do you get

out of playing with Hamid Drake? What do you get out of playing with Kent

Kessler and Tim Mulvenna? They’re all different people. They have

all different histories. You walk away from those situations learning

more than you can even assess at the time of doing them. My whole process

has been about doing as much as possible because that’s how I learn.

It may not be how other people learn, but that’s how I have to do

it.

FJ: Do you find that the more you are learning, the more that knowledge

sparks your curiosity?

KEN VANDERMARK: Yeah, definitely, definitely. You think you know something

(laughing) and then you find out that you really don’t know that

much and you have to go back. A perfect example is the tour with Brotzmann

and Brotzmann’s Tentet in the United States with adding William Parker

and Roy Campbell to his group. Just to take Peter for example. Every single

night that we played, and I think there was nine gigs in two weeks, plus

two days in the studio, I got to hear Peter Brotzmann play every single

night. And every single night, he kicked my ass so hard musically and

there was a piece that he wrote that we worked on called “Stone/Water”

and in that piece, towards the end of it, there is a section where Jeb

Bishop plays an improvisational section and then I’ve got to play

an improvisational section and then Peter plays after me and I had to

do that nine concerts plus the studio recording of it. And everyday, I

knew that he was going to take this solo after me and everyday, I would

do everything that I could possibly think of to do something that would

not make me look pale in comparison. And everyday, he came in and he just

destroyed me. It wasn’t a competitive thing, but it was like an understanding

that he is playing on such a level with so much energy and creativity,

it was just like he was knocking me all over the block. That pushed my

playing through the roof. I came off that trip with all this other stuff

that I didn’t have before. Playing with people like that forces you

to find things. It forces me to ask questions like, “What am I going

to do tonight to not look like a fool?” It pushes your curiosity

through the roof more.

FJ: Playing with Brotzmann must be like being on the on deck circle while

McGwire is batting.

KEN VANDERMARK: Yeah, it is an almost impossible task. It is a priceless

experience.

FJ: Let’s touch on the Witches and Devils project you have contributed

to.

KEN VANDERMARK: That’s a project that Mars Williams has put together

and he’s the leader of the group. We’ve been playing together

for about four years or so. He was real interested in exploring the music

of Albert Ayler and I think initially, it was to do a concert or two and

the group worked really well. Everybody in the group was very interested

in pursuing it and seeing it where it would go. Albert Ayler is an amazing

composer and he’s really overlooked as a composer, frankly. He had

a lot of interesting ideas about material. A lot of that came out of actually

trying to play this stuff and finding out how different mechanisms in

his work functioned. Initially, I was a little bit concerned that I didn’t

want to be are paratory band, even if it is Albert Ayler. Very quickly,

it was clear that we would try as a group, to take the thematic material

of Ayler and keep the spirit of it and the improvisation, but try to find

our own thing with it. It is very connected to Ayler’s work, obviously,

but I think we’re trying to find out what our voices would be in

that aesthetic and that is what has kept the group going. We’ve been

able to develop that and see what other things are possible with it and

go some place else with it. I consider myself as a sideman in that group.

It is Mars’ concept, his direction, and the way he works the band

live. It is very much in his vision of what to try to do with the material.

It’s really great because I get to come in and contribute to that,

but I don’t have to worry about being a leader for a change.

FJ: And the Spaceways Incorporated project?

KEN VANDERMARK: That came out of a concert I did quite a while back. I

did a duo concert in Chicago doing the music of Sun Ra and George Clinton.

John Corbett suggested doing something like that with Hamid Drake in Chicago

in connection with a concert that was happening to celebrate the fact

that the Empty Bottle series was three years old and there was going to

be a big party with a lot of musicians playing at it. He wanted to have

some kind of music that would be celebratory. I said that if we were going

to do this music then I want to get something electric in on it, particularly

on the Funkadelic stuff because that is such stuff because that is such

an intricate part to that music and my friend Nate McBride, who is a bass

player, is one of the few upright bass players that I know who actually

really likes to play electric bass too and he is an amazing electric player

and so I suggested bringing him in. That is how it turned into a trio.

We did the concert and it was really, really successful. We only played

Funkadelic music at the concert and then John suggested doing this recording

for Atavistic of going back and adding Sun Ra stuff to it and doing a

bunch of different material. Funkadelic music and Sun Ra’s music,

I love it. It kind of surprisingly works in a very interesting way by

playing both those musics together. There is a loose connection with their

interests in space so to speak and the aesthetics connected to getting

off the planet and finding something better. There is something really

nice of moving back and forth from the creative acoustic world of Sun

Ra and the creative electric world of George Clinton and Funkadelic. It

was fabulous. It was really incredible.

FJ: Doing a waxed overview of the projects that you have chosen to be

a part of, they are of composers that have gone unheard, Joe Harriott,

Sun Ra, and Albert Ayler. Why didn’t you just take the conventional

route and do an Ellington or Gershwin songbook?

KEN VANDERMARK: My feeling is, in the case of both those composers, that

the music that they are working out of comes out of a tonal background.

They are dealing with primarily chordal situations and that’s not

really where my ears lie. I’m not going to be a great chord changes

player. I’m just not really interested in doing that. The way I hear

music, I’m really coming out of a post-Ornette thing. The music of

Joe Harriott is really connected to starting to look that direction. Yeah,

he had a piano player in the group and stuff like that, but he was also

moving very rapidly towards something else that transcended tonal conventions

I think. Sun Ra, obviously, his early stuff is chordally based, but it

also moved very quickly outside that. Obviously, is later music was much

more sound oriented. Ayler, obviously, decimated basic tonality and was

moving towards the sound concept and those are people whose work really

hasn’t been examined outside of the primary composers. In the case

of Duke Ellington, whether it was his sidemen or other players, Thelonious

Monk or whatever, there were a lot of people who have looked at his music

and done other versions of those compositions and certainly, the same

thing is true with Gershwin. I don’t think that I’m going to

add something to that history, performance or recording wise. If I am

going to do something like that, they are going to be composers who I

have a direct affinity for. I can’t imagine doing something with

Ellington that could be more interesting than what he did. I can’t

really articulate how important I think he is now and was when he was

alive. Thelonious Monk, for example, is a starting point for me for a

lot of the things that I am interested in musically. His move towards

melodic interests versus more harmonically rooted interests in terms of

improvisation, his emphasis on the melody when he was accompanying people.

Charlie Rouse talked about how he was never told the chord changes on

the tunes, that Monk would teach him on the piano, just the melody lines.

That is the beginning of the motion towards Ornette’s whole thing,

with don’t play the background, play the foreground and his emphasis

on the melody. So I am very interested in Monk’s music and I work

on that. I’ve done some recordings and performances of Monk’s

music, but that is kind of where it begins for me in terms of what I’m

interested in doing, whether it’s my music or a composers. Those

types of writers are who I find interesting and also, people who have

been overlooked. If I am going to do someone’s work, I would rather

do Eric Dolphy than another version of “Autumn Leaves.”

FJ: Will you do an Eric Dolphy record?

KEN VANDERMARK: Yeah, actually, there is a record coming out in August

by The Vandermark 5, the new record and the first thousand copies of that

record has an extradisc in it, which is arrangements I did of a bunch

of composers that I like. There is one Sun Ra tune, but there is a piece

by Cecil Taylor, a piece by Eric Dolphy, Joe McPhee, Anthony Braxton,

and then a couple of other people. Yeah, Dolphy is obviously somebody

who I’ve got a lot of affinity for. I’ve done some concerts

of his music. I’m not overly interested in doing tons of Ken Vandermark

does the music of so and so. It is just that the projects have come up

in a loose sort of way. The Ayler thing isn’t even my project. It

is Mars’ project. The Harriott thing was a concert that turned into

a recording project and the same thing is true with the Spaceways thing.

FJ: Let’s talk about the Empty Bottle series and its impact on the

Chicago scene.

KEN VANDERMARK: It is really hard for me to be objective on that because

I am involved with booking it. I’m too attached to it. I’m sure

plenty of people feel I am overly self-promotional as it is. That wouldbe

a little bit unfortunate for me to give them even more ammunition (laughing).

I would have to say though, Fred, even trying to be objective about it,

that for me, personally, I won’t even talk about Chicago, but for

me, personally, it has been essential to my development. Getting to see

the kinds of musicians that come through there, all the work that John

Corbett’s done to bring people from outside Chicago and from Europe

into that series, it has totally changed my playing. The chance to hear

these people and in some cases play with them has opened up a whole new

perspective I have towards the music. The fact that the series is now

into its fourth year, I can’t even count how many concerts that is.

Bringing that music into a city and a city, it’s going to totally

bring in a bunch of energy, creative energy and I think it has affected

the scene here. I think the combination of the festivals and the series

has indicated what is happening right now through at least what John’s

perspective is and my perspective is. Yeah, there is a lot of people that

we’ve tried to book in there that haven’t worked out or we just

haven’t been able to do it. There are people we are not aware of

that haven’t played there yet. It is not like it is the perfect series

and there is nothing else left to do. We’ve tried to be as open-minded

as possible, but we also do the series for free. We’re not paid to

do it. Over the course of doing it, I don’t even think we have begun

to pay for our phone calls on concerts that we have done that have actually

made enough profit that we could get paid after the musicians. So, yeah,

there is a selfish perspective to be brutal about the music we want to

hear. We want to hear this music and those are the people we are bringing

in. I think there is some grossing about how we don’t have so and

so in and in general, we are bringing in people who we like and who we

respect and whose music we want to get heard. We try to be open about

it as possible. I think that it has been a really positive thing. I would

like to think that it has been an incredibly positive thing for the city’s

music as well.

FJ: Chicago seems to be the hub right now for advanced improvised music.

Everyone seems to acknowledge that but this country. What are they putting

in the water in Chicago?

KEN VANDERMARK: Well, I think that there are a lot of different factors

that have coalesced at the same time. I don’t think that there is

any way that you could have anticipated it. A lot of things happened at

once, somewhat by chance and somewhat motivated by forces. The situation

there is kind of unique. One thing is that Chicago has been a little bit

isolated. It is not on the East Coast. There is a lot of cities collected

in a very small area around New York in the East Coast. There is a very

high awareness of what’s going on in New York because of that proximity.

Chicago is hundreds of miles away. There are cities around here, but there

isn’t a very active improvised music scene in those cities. It is

like Chicago is an isolated thing. It is between the East Coast and the

West Coast. I think a lot of the players here have developed an interest

in what’s happening outside of Chicago, an awareness either through

recordings or seeing people play. Before the Empty Bottle series started,

there was an awareness of what was happening in Europe just out of necessityand

curiosity. It just seems like a lotof people here have good record collections.

Now that there is more players coming through town, a lot of musicians

here go out and check out who is coming through town to play. They are

aware of what is happening here. There is an awareness of what is happening

outside of here. I think that is true in other cities too, but that awareness

has led people like Brotzmann, when they come here, all of the sudden,

there are musicians who have been influenced by his work, know his work,

and want to work with him with a lot of enthusiasm and energy. He responds

to that. That is true of a guy like Paul Lytton and other players too.

There is already a camp of people, listeners and musicians, who are very

enthusiastic about them even before they set foot in the city. There is

a lot of people programming music, recording music, writing about the

music, who are all about the same age. They are people in their mid-thirties.

Okka Disk is run by someone in their thirties. Atavistic is run by someone

in their thirties. Writers like Corbett and other people, they are in

their thirties. I am in my thirties. We have all been working on these

ideas about music and we have all come to a similar point in our careers,

where we are able to work and actively affect what is going on and we

are all around the same age. So there is a certain peer group that is

involved in the scene here. There is people writing about it. The stuff

gets played on college radio. There is concerts happening. There is places

to play. There are more places to play and do this kind of music in Chicago

per capita musicians than in New York. There is more musicians in New

York and probably not more places to play to keep up with that. So there

is less harsh competition between musicians to get work. It is not as

expensive to live here as in San Francisco or New York or Boston, so economics

are a little bit easier to deal with. So there are a lot of factors going

into having a more healthier environment. There is a lot of curiosity.

There is a lot of awareness of what each other is doing and respect for

what each other is doing. There is a very inclusive and non-boundary oriented

perspective. I saw something where Rob Mazurek was talking about a willingness

to record with his group one day and a pop project the next day because

it is all interesting to him. If the music is interesting then do it.

All that openness has created a very creative environment right now. You

can’t anticipate how that is going to happen and for some reason,

all those things have come together and the scene has sustained itself,

in terms of its activity, for a very long time now. I would say the last

five years, I am playing all the time in Chicago. I’ve been playing

like two to three times a week doing the kind of music I play, not doing

weddings and not doing anything else but the kind of music I want to play.

Lately, things have escalated so I am out of town more now because I am

touring a lot more, but when I come back home, I played Tuesday night

and there was like a hundred and forty people there. It’s like I

don’t know what’s going on here. The audience is amazing. They

have seen a ton of music. They are very exposed to a lot of different

ideas. They are educated about a lot of different things. They’ve

got a curiosity. I don’t know what it is. When you describe it, it

sounds like you are making stuff up. It sounds like you are exaggerating

and I’m not. It is a fantastic place to be right now. People who

are not here and who haven’t been here and haven’t spent a couple

of years here think that you are just plugging Chicago because you want

to create like this whole horseshit about creating our own self-propaganda.

It’s like come and spend some time here. I can take any two weeks

and in one week period, I think like Steve Lacy, Mal Waldron, Fred Van

Hove, Peter Brotzmann, Joe McPhee, Barre Phillips, Joe Maneri, Mat Maneri,

all played in one week and that is a typical week. It may be a little

bit extreme than average, but that happens all the time. Never mind, all

the stuff that is happening in town with local Chicago musicians. It is

an amazing environment.

FJ: There is a tendency of writers when they are referring to you to address

two things, Eric Dolphy comparisons and your haircut.

KEN VANDERMARK: (Laughing) Yeah, well, the Dolphy thing, there is no question

that Dolphy has had a profound affect on my interest in music. The first

time that I heard Dolphy, I wentout and got a bass clarinet as soon as

I could afford it. I play the bass clarinet because of Dolphy. His interest

in angular lines, his rhythmic interval approach, totally has not really

been examined enough. There is a lot of implications in what he’s

doing musically. Yeah, I am interested in exploring those implications

and hopefully, I have got my own stamp on it in a way that makes it more

mine or moving towards mine. There is no question that Dolphy has had

an amazing impact on me. His writing and his composing has had a huge

impact on me. Out to Lunch is one of my ten favorite records. I think

it is one of the greatest documents of improvised music that I have heard.

I can’t make any argument against that. You’ve got me. Dolphy

is a big influence. In terms of my haircut, I don’t understand what

is so interesting about these kinds of things. I think what happens is

that people try, in writing, want to try to project who is the person

behind the music, like personality profiles. I have a flattop. I guess

people don’t have many flattops now (laughing), so that is something

that is different. Maybe Han Bennink gets that all the time. I don’t

know. I don’t have anything interesting to say about it because I

don’t think it is really that interesting. I just think that I look

a little bit different than some of the other people playing improvised

music now. In Norway, everybody there has got a shaved head, shorter than

me. I’m not really sure what the interest is there. To me, the thing

that is interesting about music is music. I think there is plenty to write

about. There is plenty to talk about. There is plenty to argue about totally

related to the music. It is utterly fascinating. I spend all day long,

everyday, to the pointof driving people that I know crazy dealing with

issues that are related to music. I think people in the media have a difficult

job. I wouldn’t want to write about music. It is very complicated

to articulate in words what happens with sound. They are two totally different

mediums. They are two totally different ways of trying to communicate.

It is a thankless, difficult task, but if you are going to write about

it, write about music. I think it is easier to write about sociology and

personality profiles to create these tensions that don’t exist between

musicians. I’ve been seeing it more and more now, this Chicago versus

New York horseshit. It just doesn’t exist. I was just on the road

with Roy Campbell and William Parker. They are great people. It was a

pleasure to play with them. We got along and we played great music together.

They are from New York. As a Chicago player, I play in New York as often

as I can when I am on tour. People say why I don’t I play in New

York more and do I have something against New York and it is like, I have

got to get to New York. It is not around the corner. It is like if I drive

straight through, it is like a twenty hour drive. So what they do is create

these things that don’t exist to try to have something sensational

to write about. I don’t know if editors push them to do that. I don’t

know where it comes from, but I think it is much interesting to write

about musically, what is maybe different about William Parker and Kent

Kessler. It is just crazy. The music is interesting. That is why the people

in the media got into it in the first place. So let’s write about

music. Let’s discuss music. Why write about haircuts (laughing)?

If you have got such limited space to write about what they are interested

in, why devote sentences to what shirt I wear or what haircut I have?

Even if you don’t like what I do, to write about that is taking away

space to complain about what I do. It makes no sense to me. That is my

response to the haircut.

FJ: People should keep their eye on the ball.

KEN VANDERMARK: Right.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and is in a minimum security

prision. Comments? Email Fred.