A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH KENNY MILLIONS (KESHAVAN MASLAK)

I have never talked to someone quite as outspoken as Kenny Millions,

once known as Keshavan Maslak. Whatever he is Millions is two things,

honest and one hell of a saxophone player. He plays other instruments

too, but they are of little interest to me. His resume is impressive,

including Paul Bley, Charles Moffett, Misha Mengelberg and Han Bennink,

easily proving my point. He is about as anti-establishment as possible

and that just wins him over more in my book. He does it all on his own,

own label, own club, own website, own way. I like. I welcome you to our

conversation, brilliantly played unedited and in his own words.

FRED

JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

KENNY

MILLIONS: I'm from Detroit. I was born in Detroit. I was classically trained,

all the way through high school and in college also. But in high school,

growing up in the city of Detroit, Motown, downtown Detroit and going

to high school there and it was an integrated high school. A lot of my

friends turned me onto Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, Miles Davis,

etcetera. They would take me to local jazz clubs in Detroit during the

Sixties. There was a lot of them at the time. Yusef Lateef was a regular

there. He lived there and these kinds of people, Joe Henderson. So as

a kid, my friends, my black friends would take me to these black clubs

and I really dug the music right away. I heard Yusef Lateef and they even

took me to hear early Miles Davis and all that stuff. So I got turned

onto it and I just wanted to play that because I always felt that jazz

music was more expression of the individual spirit, whereas classical

music, where I was trained in was more confined and rigid and you had

to play the composers just the way it was written and I didn't want to

spend my life playing in a symphony orchestra for the rest of my life

playing parts. I had something else in me, a voice in me, wanting to come

out and be free and express my inner feelings. Jazz was the music for

that.

FJ:

When did the saxophone come into play?

KENNY

MILLIONS: Well, I started playing the saxophone when I was six or seven

years old and then in high school, I got into the flute, but clarinet

and sax initially. I grew up in Motown and a lot of my friends were part

of the Motown scene and doing gigs with them too, backing up Temptations

and Diana Ross. All these people went to my high school. So we would all

play together behind these people before they were famous. This is in

the Sixties when Motown was just starting to break in the mid-Sixties.

I graduated high school in 1965, so it was around that time that Motown

was really starting to take off. Also, my influence is very much Motown,

R&B influence, because I was right there doing that at the same time.

FJ:

It wasn't as if this country was at an enlightened summit during the Sixties

and you went to an integrated high school.

KENNY

MILLIONS: I think being a musician, you always had, my perception of things,

I didn't want the same old thing all the time. I didn't want the clichés

in life. Things artistic within me saved me from being the nine to five

worker and living in the suburbs. So the music created an intense desire

to learn and find out about the world. I was hearing this music and I

was wondering where it was coming from. How the hell were they doing it?

When I heard Cannonball's records or John Coltrane or even Roland Kirk

playing three saxes at once, I was wondering, "How the hell does

he do that?" It wasn't written down. It's hard for a classical musician

to understand if it's not notated. They're just improvising and it sounded

so beautiful. It was a curiosity for me. The Sixties, of course, was a

revolutionary time in America and things were busting open anyways with

the Civil Rights Movement and all of that. It is just part of that wave

at the time.

FJ:

How did you end up in New York?

KENNY

MILLIONS: I went to high school at North Texas State University, near

Dallas, Texas from 1966 to 1970 and I got a gig on the road and that took

me to San Francisco and I lived there for two years, through '70 and '72

and I was touring a lot at the time with different R&B bands and blues

bands and jazz gigs. I met Charles Moffett in San Francisco and started

playing with him. He had a studio where a lot of young musicians would

come, David Murray and Arthur Blythe. He kind of took us under his wing.

He had a studio in Oakland actually. He would organize concerts all the

time in his studio and then Moffett got a gig to play the Newport Jazz

Festival in New York City in 1972 and so he took me with him to New York

in 1972, I think July of 1972, to play the Newport Jazz Festival and so

I decided to stay in New York from '72. I just lived there at that time.

I just moved to New York.

FJ: The height of New York's loft scene was during the Seventies, how

much of that was a factor?

KENNY

MILLIONS: Absolutely, that was the real loft scene. Now, it's a bunch

of bullshit if you ask me with the Knitting Factory and all of that.

FJ:

Let's come back to the Knit.

KENNY

MILLIONS: Yeah, OK, Fred, the loft scene was very vital from the early

to the late Seventies. A lot of great music was happening and a lot of

people had lofts. Sam Rivers had a great loft. I was playing, in fact,

when I first came to New York, Charles introduced me to Sam Rivers and

Sam hired me to play, he had kind of a small winds group. I was playing

with Sam at the time in '72 and '73. He had a loft, which was one of the

happening lofts in New York at the time. It was called Studio Rivbea and

I think he did it until like the mid-Eighties when he couldn't afford

the rent anymore. But that was a loft. There were so many lofts, the Kitchen,

a performance space in SoHo.

FJ:

Soundscape was one.

KENNY MILLIONS: The Soundscape, right. That was like the later Seventies.

Soundscape was by Hell's Kitchen if I remember. I played all the places.

In fact, Fred, I had my own performance on the Lower East Side on East

6th Street. I had a storefront and I would organize my own concerts there.

It was a very vital time in New York. There was a lot of activity, a lot

of great music being created and performed. It was the start of the real

new music scene or the downtown music scene or whatever you want to call

it. Of course, New York had the Sixties thing with Ornette and Albert

Ayler and those cats, but this was a further extension of that where it

really started taking off.

FJ: Why did the growth come to a dead halt in the Eighties?

KENNY

MILLIONS: (Laughing) Well, you know, Fred, it's like any other major city

in the world, the landlords get greedier and the property values go up

and artists are, of course, the first ones to get kicked out. SoHo in

New York is a very trendy, only rock stars live there now in these lofts

because they're the only ones that can afford it. But at the time, you

could get a loft, this was thirty years ago, in SoHo for like two hundred

bucks a month for five thousand square feet. The artists started a trend.

That was a place where they could get a cheap space, play their music,

have their own concerts. It was just warehouses. There were all these

warehouses, like over a hundred year old warehouses in Manhattan and artists

would do their things there, open art galleries, loft concerts, you name

it, just a vital movement. It started getting more and more trendy. People

from the Upper East Side, Upper West Side started to go downtown to go

slumming with the artists and the money people started going downtown

to hang out and realized that they wanted to be hip too and all the Yuppies

started coming down and the people from Long Island and whatever. They

wanted to come down thinking we want to be cool artists too and daddy's

going to pay our rent and so the landlords started jacking up the rent

and all the artists got pushed out. Sam got pushed out. I left I got pushed

out in '86 because it started getting to be too much for me. There wasn't

any vital music scene happening like there was in the Seventies. It all

started dying and becoming more commercialized, even in the jazz world

and the free jazz world. It started getting more commercialized and a

couple of people get all the gigs. It changed a lot. As the property value,

the real estate value started skyrocketing in New York City, these neighborhoods

like the Lower East Side, where I lived and SoHo, now, the Lower East

Side, you can get a closet for like two thousand a month if you're lucky.

Just the Yuppies can afford that. They remodeled the buildings. I suppose

it's cleaner now. New York has really changed and for me, it's not the

vital scene anymore. It is still a great city. You can have fun there

and go shopping and go to some nice restaurants, but as far as the music,

it is further diversified now. It used to be Mecca, years ago, but it's

no longer Mecca, because the world has become a smaller place and the

musicians have diversified so it is not necessary to live in Mecca anymore

because you can find great music and great musicians anywhere in any city

in the world.

FJ: As stagnant as New York has become, it is merely a sign of the times.

KENNY

MILLIONS: Yes, this is very true, Fred. It is a sign of the times. The

music is very stagnant there because everything has to become commercialized

for people to exist there. There is no such thing as getting paid in New

York. Everything is a door gig. This is ridiculous. But the musicians

feel they have to do it. They have to play in New York because it's New

York. I know people that drive from Florida just to play at the Knitting

Factory for the door. It's ridiculous. It's absurd because the owner of

the Knitting Factory is getting rich and these musicians are still chasing

the magic dream, the carrot dangled in front of their nose. They're still

thinking that they have to play the Knitting Factory and it is going to

give them their big break, which is a bunch of bullshit.

FJ:

A generation has been born into a period where there's been no innovation

in improvised music. It is no wonder there is nothing to talk about in

jazz. There isn't anything worth the time.

KENNY

MILLIONS: That's true. In my own personal experience, I saw it dying in

the, as far as the innovation, in the Seventies, it was still happening.

There was a lot of hope, even for young musicians like myself at the time.

There was gigs to be had. There was European tours that paid you money

and there was concerts around America that paid money and there was a

vital scene in the Seventies. So there was an interest in it. The critics

were into it. You could get a write up in the Village Voice and the New

York Times. It was a real happening scene. Now, I would say since the

late Seventies, early Eighties, it really started changing as far as my

perception of it. There's still great musicians out there. There's still

people that are trying to do things, but you don't really see them or

hear about them. There's very few venues that they can perform at. So

it's become a very limited thing, down to a few people, a few handful

of people that get all the gigs.

FJ: So you left Mecca.

KENNY

MILLIONS: Well, I was getting burned out. I was touring a lot. When I

was younger I was going to Europe every other month. That kind of saved

me, but I didn't want to live in a closet for the rest of my life. As

you get older, you want to relax a little bit more, have a little bit

more comfort. That's only natural to the human existence. So therefore,

I didn't want to end up like, I used to call them New York stories. I'd

see these old people, like old burnout artists that would live in my building

and you could tell at one time, they were really into something and now,

they're just old and crotchety and no one gives a shit about them anymore.

And you could tell that they were just living in their memory of the Fifties

or the Sixties or whatever and they're just getting more pitiful looking.

I didn't want to end up like that. I didn't want to be another New York

story, become a pitiful guy, lonely guy in the hallway, walking around

and saying how the world doesn't appreciate me and doesn't understand

me and doesn't give me respect. So I wanted to change my life because

I didn't want to end up like that. It's very easy to end up like that

in New York City. You get so attached to that excitement and the dream

of actually getting respect and getting exposure and making it that you

get caught up in this fantasy that you might be eighty years old and you're

still thinking about it. I didn't want to end up like that because I think

that's a very sad story.

FJ: But why Florida?

KENNY

MILLIONS: I figured by that time, I was already touring Europe a lot.

I had been to Japan and all that stuff and getting my reputation going

in those countries. I thought that it wasn't necessary for me to live

in New York anymore. The real good concerts, the concerts that paid me

good money were in Europe or in Japan, so I could live anywhere, right?

So why should I live in New York in a closet that's getting more and more

expensive every month? So I thought I could live anywhere, so I just picked

Florida because I enjoyed swimming and I enjoyed being outside and I enjoyed

healthy things and figured that if I'm down in Florida, I could swim everyday.

I basically swim everyday.

FJ: So you are doing the things.

KENNY

MILLIONS: Yeah, I enjoy myself. I can relax. I have a decent life. I'm

happily married. I have a nice house. I run my own business. So I have

a decent life and I feel like a decent human being instead of some sort

of burnout cockroach in a closet in New York. I got afraid, Fred. I did

not want to end up like a loser. It's so easy, being a musician. I've

seen so many of my friends burnout. Half of my friends are dead or are

crazy by now. Out of the ones that survived, there is probably ten percent

that I can even talk to, that are not completely insane or dead. So I've

seen in my own personal life and in my own struggles to be an artist,

I've seen what it can do to you if you don't watch out. It's a very addictive

drug, having a career is a very addictive drug that is very destructive

if you are not careful. So I had to re-evaluate and analyze my situation

and decide that I wanted to be around for quite a while playing music

and I don't want to have a short life and they're talking about me ten

years after I'm dead. I don't give a shit about that. I want to still

be playing for a long time. I want to still be working when I'm ninety-five

(laughing).

FJ: You're basking in the Florida sunshine. You're swimming in the ocean

everyday. You are relaxing and enjoying life's pleasures on your own terms.

Why bring on tax of starting a label?

KENNY

MILLIONS: There is reasons why I do that also. Ultimately, it is artistic

freedom, Fred. I still play the label game once in a while. I still have

some contacts with certain labels that I negotiate with from time to time,

but I'm not dependent on them. I enjoy my independence to do everything

that I want to do. Through my experience of different labels, they always

no matter if it's in free jazz or jazz, they always are going to give

their opinion as far as what songs you should do or how you should comb

your hair. Their opinion is involved because they're the record producer

and ultimately, they want to sell records too right? That's just the nature

of survival, is to sell records. They don't want to keep losing money.

So they want you to play this song or hire this guy to play with you because

we can sell more records. In jazz or free jazz especially, what can you

say? You can't sell more then two or three thousand copies of anything

if you're very lucky. That's the most you can sell, but still, they want

to have their power trip and I resent the power trip. At this point in

my life, and being through what I've been through, I don't want nobody

telling me what I should do or who I should do it with. I have a lot of

tapes, old tapes in the drawer, something I just finished with me and

Charles Moffett from 1981. I'm negotiating with a couple companies and

if that doesn't work out to my satisfaction and I don't like the deal,

I'll just put it out myself (laughing).

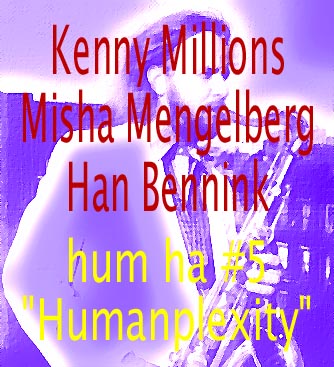

FJ: You re-released Humanplexity with Misha Mengelberg and Han Bennink.

KENNY

MILLIONS: Well, Humanplexity was Leo Records first recording in 1979.

I started his label. Him and I had a big falling out. He contacted me

in 1979. I was living in Amsterdam and I was playing with Han and Misha

at that time. We were working a lot in Europe and I was living there.

Leo heard about us and he was living in London and he came over and he

wanted to record us. He was starting this record label and I said that

we would be his first date and so we were his first date. That was on

LP for a couple of years and then, in the Eighties, for some weird reason,

it's a personal thing between him and me, he decided to kill the recording

and not have it on his catalog. And I think it's a very good recording,

but for some strange reason, that I still don't understand, he killed

it in the Eighties. So I said, "What the hell, I don't need him.

I don't need anyone." I re-mastered it. I didn't have the tape. I

took the LP, my one and last copy of the LP and with today's technology,

I converted it to CD, a digital CD. I do the mastering myself on my computer

and worked on it for a couple of weeks and it was really hard because

there were a lot of scratches and pops in it, noises and so I worked on

mastering it for a couple weeks on my home computer and redid it, which

I'm glad I did.

FJ: Junko's Dream is another find.

KENNY

MILLIONS: Yeah, that's a good one with Paul (Bley). That's another one

that originally came out on Leo, but him and I have fallen out so he doesn't

do shit for me and he's killing my recordings. My opinion is it's the

artist that owns the music. The record company might own that particular

tape, but they don't own the soul of the music, the artist does. So I

feel that I have the freedom to do anything with my music that I want.

It's my music. It's my compositions. It's my music that I sweat and labored

over and put my soul into. No jive ass producer is going to kill my hard

work over all these years, Fred. This is another subject. It is crucial

for me that artists take more responsibility for their careers and for

their destiny. This is one way for me to do it. Standing up for your rights

as an artist because it's become so lopsided now where the middlemen control

everything. The Knitting Factory controls everything. They can dictate

that they aren't going to pay you and that you have to play for the door.

But they line up around the block with their tongs hanging out asking,

"Can we please pay for the door? Please let me play at your great

Knitting Factory." And the record companies do the same. "We

don't need you. We've got ten thousand others just like you and younger

than you and they don't want anything. So what do you mean when you say

you want two thousand dollars for this date and I've got this fool over

here that wants to do it for free?" It's very important, Fred, as

far as attaining artistic respect. There is very little artist respect

that you feel from record producers, critics, the media, concert promoters,

agents. Usually, they're on top of you. You're kissing up to them constantly.

And I refuse to play that game.

FJ: You have essentially been blackballed by the media.

KENNY

MILLIONS: When I was in New York and I will just give you a couple of

examples, Fred. When I was in New York in the Seventies, you know Stanley

Crouch, right?

FJ: Sure.

KENNY

MILLIONS: Well, Stanley's a friend of mine and we used to hang out together

in New York when David (Murray) first came there and I was a friend of

David's from California. So Stanley and David and me would hang out together

on the Lower East Side and I got to become pretty friendly with Stanley.

He was just new in New York. He was a writer and a drummer. He was saying

that I played good, but I can't write about you. I say, "Fuck you,

Stanley. We're still friends." But that's how it is. It's a business.

So they've got to do what they've got to do. He's got to write about who

he's got to write about to keep the books and magazines sold. They don't

want some white boy that will blow his black idol off the stage. I don't

mean to sound racist or nothing. I'm just talking about reality, as far

as my reality of what I experienced.

FJ: The reality is that European innovators like Peter Brotzmann, who

has been every bit as influential, if not more than most of his American

counterparts, does not get nearly press that a Keith Jarrett receives.

KENNY

MILLIONS: This is true. Well, you've seen the history of Jazz just last

month right, the history according to Wynton Marsalis and his mafia. You

think they're going to put someone like me on that program to talk about

the history of jazz. They're a lot of great musicians out there that know

more than Marsalis, but he has the image. He's from New Orleans and he

has the right this guy and that guy backing him. He's got the right image

to sell records, the right front. The industry and the critics are always

looking for the right image. The people that control the industry are

the critics. Someone told me a long time ago in New York, "If you

want to become famous, just get friends with Gary Giddins." (Laughing)

I said, "I'm sorry. I just can't kiss ass." I'm not going to

do it. I'm not going to kiss anybody's ass. I have enough self-respect

and pride not to play that game. I'm very anti-social, a very private

person. I never did drugs. I was very anti-social as far as they're concerned.

I don't play the game and kiss up to them, which they expect. So if you

kiss up to the mafia, which are controlled by the critics and the few

musicians they deem important, then you're not going to get exposure.

You're not going to get the recognition. That's just the way it is. It's

set up that way. It's set up to sell magazines. It's set up to sell records.

It's set up to make business. They told Louie Armstrong when he came back

to New Orleans with Jack Teagarden, "Make sure and not have Jack

Teagarden in your band. He's white." That was Louie Armstrong and

so he said, "Fuck you. I'm never going to play in this town."

So that's the way the business is. It's always has been that way and it's

more so like that. If people think that free jazz or jazz is any different

they're crazy. They're all this commercialization, all the games are within

the jazz world too. It is just the same as the pop world. It is just on

a much smaller level. There is so much less money to fight over, but still,

they're fighting over it and killing each other for a couple of little

door gigs. I don't play the game. That's one reason why I left New York.

I got tired of the game. I figure Florida, there is no culture here. It's

a nice place to live and it's healthy. It's 82 degrees today and it's

February. There is no music scene. It's like bar mitzvah scene and I don't

do that. But I enjoy it because I'm aloof. I'm detached from the same

old bullshit. I just want to play music and do my music and not have anyone

tell me how I should do it.

FJ: Does it agree with you that Wynton, nowhere near an innovator in jazz,

is rewriting the history of the music?

KENNY

MILLIONS: It pisses off most musicians that have been around. They think

he's just an arrogant prick, which he is (laughing). He's obviously had

all the breaks. He's never had to drive taxicabs. He's never had to really

pay dues and play clubs dates. He had the right credentials, from the

New Orleans scene, from his father. He had all the right credits behind

him. They needed a new Miles Davis. So they found their boy. I think it

pisses off most musicians that are of an older generation. The ones I

talk to just can't stand him and can't stand listening to him. It is such

a limited perspective. I'm not taking anything away from his talent. He's

obviously very talented at copying everybody, but he really doesn't have

his own voice. He's the godfather now and so therefore, you have to play

it according to his rules or you're not going to make it in the New York

scene. He's the head of the jazz scene there.

FJ:

What the hell is a hum-ha horn?

KENNY

MILLIONS: It's my little invention in the Seventies when I was living

in the New York scene during the heavy avant-garde thing. I put together

a valve trombone, trumpet bell, and a saxophone mouthpiece. It was three

instruments in one and it's on that Humanplexity record. It has a very

low, wild sound and then it has a very high sound. It has no midrange

what so ever. It's a very strange instrument (laughing). I don't play

it anymore. It just collects dust. It was part of my time in the Seventies

in New York. It kind of represented that. It is a very avant-garde thing.

I used to put these sparklers on it and children's toys and I would turn

off the lights and it would come to life. It was a whole light show going

on.

FJ: Don't you think you risk becoming a jack of all trades and master

of none?

KENNY MILLIONS: I try not to play too many things. When you go to music

school in college, they try and teach you different instruments because

they try and make you a music teacher. So I had basic knowledge with percussion

instruments and string instruments because you had to learn that. I used

to work as a drummer too because my brother was a drummer. So I still

play drums and once and a while I'll play a gig on drums. But I don't

consider that a serious instrument. I've messed with them.

FJ: What is your serious instrument?

KENNY

MILLIONS: Saxophone, clarinet, and flute are quite serious instruments,

that I take seriously and really practice. Everything else is just some

nuances, just some garnish on the plate (laughing). But I try not to get

too hung up with that. When I was playing with Han, I was picking up everything.

I've kind of lost appetite for that right now. I would rather just be

a good musician and keep myself together on my main instrument.

FJ: You have a particular torn in your side about the Knit.

KENNY

MILLIONS: (Laughing) He's an entrepreneur of exploiting musicians. He's

been great at it. It's the typical story. It's so typical of the middleman

story, getting rich and famous on the backs of musicians and artists.

He's clever. That's what Leo does too. That's why he has so many releases

out. He doesn't pay anybody, but they all beg to be on his label. These

middlemen, they are in control. They have all the power. The musicians,

it's half their fault. I'm not going to blame it on just these guys. It's

a fifty-fifty deal here. It's fifty percent the musicians' faults for

allowing themselves to be exploited. I played the Knitting Factory in

1997. I was invited there, my friend just died, Sergey Kurokhin died and

they were having a Kurokhin memorial and festival at the Knitting Factory

in New York at the beginning of '97. The organizer flew me up from Florida,

provided for me. He paid for me to come up there. That was a private sponsorship.

So I came up to do that. So I checked out the scene then and thought it

was a huge operation. He's got like a hundred people working for him and

a thousand musicians kissing up to him and these guys fly in from around

the world just to play there. This guy was a clever hustler. I should

learn something from him as far as how to hustle. This guy has pulled

some shit over their eyes. It's pitiful. I saw how the musicians behaved

there. They were acting like this was the Carnegie Hall of the new music

scene. I was just thinking that this was some stupid loft that wasn't

even around in the Seventies. I was playing the real lofts, where the

real music was at and where the musicians used to get paid. No one was

kissing no one's ass because everyone was independent and the musicians

used to run the lofts not the businessmen. I said this is pitiful. I'm

never ever going to be involved with this bullshit again. I don't care

who tells me what and one thing I don't need is a door gig at this point

in my life.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and has a hitman looking for Martha Stewart.

Comments? Email Him