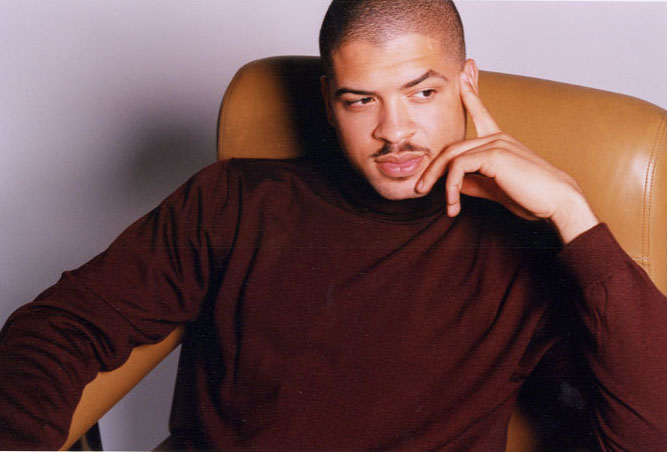

Courtesy of

Jason Moran

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH JASON MORAN

October 25, 2001

Frankly,

I am not qualified to offer up an opinion of improvised music. And I am

confident that no one outside the artists themselves are truly qualified.

So my approach to Firesides has always been to never be presumptuous enough

to interpret the artist's words or offer up context to them. Instead,

I have always done the only thing I know how and that is get the fuck

out of the way. Having said that, allow me to return the stage to the

one in the arena. Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Jason Moran, unedited and

in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Between the two of us, we have done a dozen lifetimes worth

of interviews. What question do you get the most?

JASON MORAN: Where do you pull your resources from? Where do you get your

influence? I think that's it. I think that's the popular one almost for

everybody.

FJ: Shit, Jason, even I've asked you that one.

JASON MORAN: Yeah, but everybody asks about it.

FJ: So what question would you like to answer?

JASON MORAN: Oh shit, Fred (laughing). Why are you a jazz musician (laughing)?

FJ: Why are you a jazz musician?

JASON MORAN: I don't know, Fred. I don't know (laughing). As many people

say about being an artist, "you don't choose it, it chooses you,"

when I started playing piano, that's not what I was close to envisioning

myself doing at well over thirteen years old. I never thought that I would

do this for a living. I even quit at a certain point. But when I started

playing again, I still wasn't really convinced that I wanted to become

a musician, even though I went to a performing arts high school and started

studying music pretty seriously and then went to college at the Manhattan

School of Music. And I have friends who, I remember being in college and

still wasn't sure whether I wanted to be a musician or not because the

lifestyle is so sporadic, at least for me it is. For some other people,

it's not, but for me, it's up and down and it's not as, well, you plan

things six or seven months in advance. It's not really direct. What you

hear today may not affect your music until a year and a half from now.

So you don't see the direct effects on your musical and your art form

as you do if I made a sale today and I was a stockbroker, then I could

get my check. At the end of the day, I could get my commission for it.

But with art and with other shit, it takes a long time. So I thought that

it chose me at a certain point. I think I am one of the luckiest people

in the world. I do what I like for a living. I stay at home when I want

to stay at home. I go on the road when I want to go on the road. I'm able

to pay my bills. I am able to think that when I go to see movies by Alfred

Hitchcock or whoever else, that that is just not entertainment, that it

is actual research. That is probably my main reason for becoming it because

I enjoy doing it. It is not like I said, "I want to become a musician

and tour the world." It was just, "Well, can I make a living

doing this?" And I did it. So now I'm doing it and I enjoy it.

FJ: If you are a sporting man, you validity is an easy gauge. If Michael

Jordan scores forty plus in a game, his prowess on the court is defined.

It must be trying to be involved in an art form where your legacy and

your authority may not be determined for generations to come. That was

the case with Albert Ayler. With that in mind, how do you gauge your own

development?

JASON MORAN: I can listen to it from record to record. I am able to assess

myself objectively as to what portion of the record that I thought I was

bullshitting on and points on the record where I thought I had excelled

or had gotten a lot better at certain things. I can listen to my solo

pieces from each record even though they are all kind of different. I've

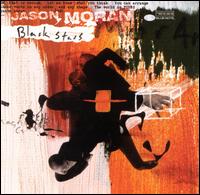

been playing that Jaki Byard song that is on Black Star for, since I was

in college and each year it's kind of progressed as a piece. So I am not

comfortable enough to record it. If you are able to listen to it, just

like you are able to go see a Jackson Pollack retrospective and look at

his early work, but when he got into his drip thing, he went into a totally

different direction. And then, at the very end of his career, he almost

went back to the form a little bit. You're able to look at it, but you

have to look at it with a wider vision. You have to kind of stand a little

further back, rather than look right at just the numbers. If you want

to gauge your artist relevance on how many record sales, I have none (laughing).

You are able to do it. You are able to listen to your compositions to

see in what areas they've grown, your improvisations and how you interact

with the musicians. I think that's almost the main point of how your band

functions. I think that from record to record, especially with the rhythm

section that I have chosen now to play for the past couple of years, that

it has moved in a certain direction that I couldn't have predicted. It

went that way because when we first started experimenting with a lot of

that stuff, people shunned it. "You all can't even play time,"

or, "you can't even keep a groove for a little while." You want

to move away from this so fast, but now it has developed into something

that I regard as being our style. It is the trio's style.

FJ: The music industry is all about record sales and if it wasn't Cecil

Taylor and Andrew Hill would have contracts with Interscope and Arista.

So it behooves an artist in today's climate to lull the masses and to

appease the rank and file with one release mirroring the last as popular

musicians do. One U2 album sounds like the last. An example of this is

a peer of yours, Brad Mehldau. How many volumes of that fucking Art of

the Trio has he done?

JASON MORAN: I don't know, about six, seven, five.

FJ: He has worn the treads off that fucking tire. No one else has the

patent to Art of anything after this guy. But the guy's got record sales.

In my opinion and I am merely one man, you are a better piano player.

Why aren't your sales numbers where his are?

JASON MORAN: Well, that is a really difficult question. I can only speculate

as to why some artists are more popular than others. I am still relatively

new to the game. I've only been doing this for four years. I haven't played

sideman on a billion records. I have been associated with Greg Osby, people

who are off the treaded path. I'm not as mainstream as an Eric Reed or

Brad Mehldau. I am not comparing the styles between each of us, but I

think that is part of it. The people that I regard and that I pattern

myself after, they weren't selling records, Andrew Hill, Muhal, Jaki Byard.

If that is the clique of people that I often hang with and the people

that I hold in high regard, then I'm probably going to travel that path

for a while. When I do a performance, whether I go back to back with any

trio or whoever the group is, the people feel that energy whether they

want to admit it or not. I've had people who never listen to music be

like, "I've never heard anything like that before in my life."

I've had people who listen to music all the time say that. I am not going

to gauge at this early point in my career, state what the rest of my career

is going to do. Who knows? Maybe the next record will sell seven hundred

thousand copies. Who knows? I think it's more of a mainstream factor.

My songs that I even think swing, they don't swing the way all the stuff

that I hear on WBGO swings. It is like a totally different connotation.

When I say swing, it is not like the Art Blakey style. I come from a totally

different crew of musicians that I value as an art form very high.

FJ: Why haven't you whored yourself out and played more as a sideman and

guest on records more frequently?

JASON MORAN: Nobody ever asked me to, Fred. That's the point. Nobody's

ever asked. I'm not going to go out and say, "Hey, can I play on

your record?" I think that is crazy almost. "Hey, can I be in

your band?" There are some bands that I would love to be in. Play

once with Dave Holland or Jack DeJohnette or Roy Haynes for that matter.

There are bands that I want to be in, but I don't know how to approach

a person like that and say, "Can I be a part of your clique for one

tour or one gig?" But it's more of just that people have never asked.

That's the main thing. Maybe they think that with the crew I'm associated

with, that I don't want to do anything else. If it's not of a certain

style then I don't want to play it, which is far from the truth. I will

judge stuff accordingly and I won't play on just anybody's record.

FJ: Both Andrew Hill and Muhal Richard Abrams have made seminal albums

that have expanded the vocabulary, but both have languished in relative

mainstream obscurity. If that should be your fate, would you be comfortable

in the underground?

JASON MORAN: Yeah, Fred. I'm very comfortable with it. My point overall

is that if I'm looking for financial security in my life, then I probably

won't do it through music. I would probably have some side hustle that

nobody would know about that will allow me to live the way I want to live

comfortably in a big house, if I want a big house in Texas somewhere and

have a couple of cars. There's a way to have that. It depends on what

you want out of life. Part of the thing is that I want a family and the

comfortableness is that when I have my children and I go on tour during

the summer that I will be able to bring all my children with me to travel

throughout wherever I go. So that's what I want and then at the same time

be making music that I think is really hip. But I'm very comfortable with

it. I'm young and I'm dumb as I always say. Twenty-six, so I can make

stupid decisions for the rest of my life, but as long as I live by them,

I have no regrets right now, none, for anything that I've done in my life.

I'm just going to keep on going. If Muhal can be happy with it, as he

obviously is, I regard him as an artist in his highest form. The artist

doesn't have to be famous. The artist doesn't have to be rich. The artist

has to create art and that's what he does. And usually that always turns

around in some strange fashion. I mean, Muhal has supported himself and

his family for many, many, many years and the thing is that he does it

in a way that not everybody knows how he does it, which is illusive and

his music has that element in it. He's always applying for grants and

he always has his ensemble, the AACM, performing and doing concerts all

the time. There's a lot to learn just on that level, how he created an

organization that is able to be up and running forty, forty-five years

later.

FJ: Are you looking to form an AACM?

JASON MORAN: I don't think I'm that good a leader, Fred. I don't think

I'm an organizer of thought. I couldn't do it probably. I would be too

selective in the people that I choose and then it shouldn't be up to me

to choose people to be within it. It should just come together almost

as if it was unplanned. I don't know if I think that similar to that many

people to be associated with a group like that. I just don't know many

people who would be really, really interested in it and have it be like

a membership of twenty or thirty people.

FJ: It is a logical pairing to have Sam Rivers on your latest, Black Star.

JASON MORAN: Right, I called him on the phone. Plain and simple, I asked

Greg, "Greg, what's Sam's number? I want to see if he'd want to do

this record." I got his number and I called him. Strangely enough,

he'd read an article about me two weeks before. I talked to him and told

him that I play with Steve and Greg and loved his music ever since I started

listening to jazz. He's says, "Oh, great," so I sent him my

first two recordings and he was down. So I proceeded to talk to him every

now and then before we did any rehearsals, just to get comfortable from

man's standpoint, man to man, just how you talk to each other, just learn

some of his stories and listen to him talk about composition and stuff.

So it was really easy to record with him. Plus, I've had connections through

Andrew Hill and Jaki. I studied with both of them and Jaki was his roommate

and Sam and Andrew recorded many records together. So I had like this

second or third, I was like the son of them, playing with like an uncle

or somebody.

FJ: His recent projects are pretty avant-garde, is that a direction you

would like to explore?

JASON MORAN: No, I don't think I'm that creative, Fred. He was saying

that he and Dave Holland would play concerts all the time and then would

play for two hours at a time, just straight without any music and I don't

know if I'm that creative, honestly, Fred, to be able to just go and not

know where I'm going. I don't know that much about music to do that yet.

FJ: You think you will get there?

JASON MORAN: I hope so, because that is pretty impressive. Whether you

want to admit it or not, even if you just bang on a drum for two hours,

it still takes concentration (laughing). I have a lot of studying to do

before I can even reach a point where I thought I would be comfortable

doing that. You never know, Fred. You never can tell. Who knows?

FJ: And the future?

JASON MORAN: I'm actually composing music for a solo record, a solo piano

record that will chronicle my family history as well as chronicle the

piano jazz repertoire going back to the 1700s, where I know some of my

family started in Louisiana. At least that's all the records I have up

to was the 1700s. We'll start from there and all the pieces will be related

to relatives and then also, at a certain point in the recording, I will

start to relate those ancestors with the teachers that I had like Jaki.

He had a series of pieces that were dedicated to the masters. He has one

called "Garner in the B," dedicated to Erroll Garner. "Out

Front" was patterned after Herbie Nichols. I want to do a solo recording,

just another test. I always think of my recordings as tests and documentations.

That's what I'm working on now, as well as a score for a short film project

that a friend of mine did. I also got a grant to write some works for

my trio, but also feature voices or languages from around the world so

each piece will be based on the dialect of Japanese or Italian or Turkish

or Danish or whatever else. So I have these compositions that are transcriptions

of somebody speaking in that language. I have a number of projects to

work on right now.

FJ:

Life in New York get back to normal?

JASON

MORAN: Nope. People are really trying to act like it is, but everybody

over here is pretty scared. I still walk around the city and I still haven't

been below 23rd Street yet except for one time and that was only for four

hours. So I've stayed pretty much uptown. This city is just too small

that if something happens, it will affect everybody anyway. The city won't

be back to normal for another two, three years depending on the way this

war will go.

FJ: You and I are big Godfather buffs. Have you grabbed the DVD?

JASON

MORAN: Did you?

FJ: You know I got mine.

JASON

MORAN: You got it (laughing).

FJ:

I preordered that shit eight months ago.

JASON

MORAN: (Laughing) Really? I just ordered it a couple of days ago and it

will get here next week. I can't wait. Can't wait. I'm reading this really

interesting book called Easy Riders, Raging Bulls and it's about all those

directors in the Seventies like Scorsese and Coppola and Woody Allen and

Dennis Hopper and that whole Hollywood scene in the Seventies and how

crazy everybody was and how most of those movies that became hits weren't

planned that way. It's really interesting. But they talk about The Godfather.

Coppola didn't really want to do it because he thought that the book was

such a best seller that he'd sell out and they really had a hard time

convincing him to do the movie. They had a really hard time getting him

to do the second one and the third one.

FJ:

The third one was misunderstood.

JASON

MORAN: First two were classics. I think the third one was still good as

a movie, but it just doesn't measure up to the other two. I think it's

still a good flick though.

FJ:

And we close another page.

JASON

MORAN: Yeah, it was good to talk to you again, Fred.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and is in the new time slot after Friends.

Comments? Email Him