A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH JOSEPH JARMAN

I can't remember the last candid one on one that Joseph Jarman has done.

So I consider it a great honor and privilege that Jarman would grant the

Roadshow this intimate portrait. When I see how weak the current state

of the music is, I only look to Jarman and his AACMers to find hope. Hope

is all we have and I cling to it daily. May I present Joseph Jarman, unedited

and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

JOSEPH JARMAN: I got started playing by growing up in Chicago in the middle

of the bebop jazz scene. Every time that I went out, there was music everywhere.

There was also a lot of music being played in my household by my relatives.

I went to high school at DuSable High School, where a famous teacher,

Walter Dyett taught many, many wonderful musicians. That's where it began.

FJ: When did you pick up the saxophone?

JOSEPH JARMAN: I picked up the saxophone while I was in the army. I studied

drums in high school and in the army, I picked up a saxophone and a little

later on, I got transferred to the 11th Airborne Division Band. I began

playing there within that band for about a year. Then when I got out,

I met Roscoe (Roscoe Mitchell), who introduced me to Muhal Richard Abrams.

I was going to school with Roscoe Mitchell, Malachi Favors, Anthony Braxton,

Henry Threadgill, a whole bunch and we all were sort of stuck together

and we began to play in, we had a little study group and then after the

study group, we also worked with the Experimental Band of Muhal Richard

Abrams. And then a little later on, the AACM was born. And then in 1969,

the Art Ensemble of Chicago was born.

FJ: Muhal Richard Abrams, Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton, Malachi Favors,

and Roscoe Mitchell were in one school with you, what school boasts such

distinguished alumni?

JOSEPH JARMAN: This was at Wilson Junior College. And there was an enthusiastic

teacher named Richard Wang, who is a professor now at Illinois University,

who was very enthusiastic about "jazz" and he would allow us to have jam

sessions. He got in a lot of trouble. He would write Charlie Parker solos

on the board and have us analyze them. He got in a lot of trouble because

of that because they didn't want to teach "jazz" at that time. They were

just supposed to be teaching music.

FJ: What was the administration afraid of?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Well, at that time, there was also political upheaval in

the whole country because of the war in Vietnam and because of the race

relationships between blacks and whites in the country. It was also the

beginning of the awareness movement of the intellectuals that became known

as hippies and later became known as flower children. So all this kind

of stuff was going on.

FJ: Yet, you gentlemen formed the AACM in this volatile social climate.

Why?

JOSEPH JARMAN: To create opportunities for the musicians to be able to

perform their music without disgression and without intervention and to

generate a feeling of respect and camaraderie among this group of musicians

that were so adventurous that they had very few opportunities to perform

in regular situations.

FJ: So there was a prejudice toward musicians that chose to play adventurous

music?

JOSEPH JARMAN: The opportunity to perform? Yes, it was missing. Only those

musicians who performed bebop or post bebop were able to work constantly

or were able to really have an opportunity to perform. The Experimental

Band allowed us to experiment in large ensembles and then the AACM allowed

us to experiment in smaller ensembles.

FJ: Has the AACM accomplished its initial goals?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Yes, it is still accomplishing those goals today.

FJ: And do you consider yourself a current member of the AACM?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Yes, I do.

FJ: Let's touch on your work with the Art Ensemble.

JOSEPH JARMAN: It was formed in 1969. At the time, Lester Bowie was President

of the AACM and one day at one of the meetings, he asked me as he had

done with Roscoe Mitchell and Malachi Favors, if we would like to go to

Europe to Paris. And of course, we immediately said yes because that would

give us more freedom in the expression of the music. And so we went in

July of 1969 to Paris and had a small house in the country. Someone came

and asked, "What's the name of this group?" Our response, collectively,

was the Art Ensemble of Chicago. It was a wonderful and extraordinary

time, Fred. Overwhelming in both musical and worldly experiences because

it gave me the opportunity to travel all over this planet and several

others. I also got the opportunity to continue to express the experimentation

because the Art Ensemble eventually became interested in the performance

of what you may say was world music. There was not a form that it did

not engage, Asian forms, African forms, Eastern European forms, gypsy

forms, South American forms, island forms, classical, traditional western

and both European and American forms. Everything was available.

FJ: The variety of instrumentations that the Ensemble had at its disposal

could not have hurt?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Yes, because the idea was that every sound was available.

Every sound is possible. Whatever you hear in music, you are able to produce

it. This was really the reason that there was such a multiple factor in

the instrumentation of the Ensemble.

FJ: Did you or any member of the Art Ensemble feel limited musically?

JOSEPH JARMAN: No, one would come in with one form and if there was a

problem, he would teach the others that form and move on.

FJ: What is the legacy of the Art Ensemble of Chicago?

JOSEPH JARMAN: I really have no idea. That has to be left to the listeners

and the historians. That has to be left to the people who listen to the

music. I have no idea what that legacy will be because there are so many

different aspects and so many different views. I think I would like to

leave that up to you, for example, rather than try to categorize it myself.

FJ: Why did you leave the Art Ensemble?

JOSEPH JARMAN: I left the Art Ensemble because I became a Shinshu Buddhist

priest and I was already operating an Aikido dojo in Brooklyn. It required

more and more of my time to engage in those activities. We are also associated

with the International Zen Dojo, which is affiliated with Chozen-ji Monastery

in Hawaii and Aikido Association of America, founded by Shihan Fumio Toyoda.

I was ordained as a Shinshu priest and that aspect slowly began to draw

more and more of my energy towards it. So I had to choose between the

constant traveling with the Ensemble because it constantly traveled. That

was its thing. Or to devote more time to these other studies and practices.

FJ: As an Asian, I am curious as to how Eastern philosophy and religion

has impacted your life.

JOSEPH JARMAN: Tremendously, tremendously, tremendously, without it, I

am sure that by now, I would have made transition in being in a completely

different zone (laughing) because I had very, very traumatic experiences

between the ages of seventeen and twenty and after those very traumatic

experiences, I was invited to a party and there was this guy over in a

corner who was getting all the attention and I was very egotistical in

thinking that I should be getting some attention too. So they introduced

me to him and he said, "I will give you ten thousand years and then I

will kill you." That was the beginning and my introduction to Buddhism

(laughing). It was very interesting and it still is today.

FJ: Do you ever regret your path of spirituality, that you did not continue

your formidable musical journey?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Absolutely not. To me, it is much more valuable to share

the reality of how to fall down and how to stand up under any circumstance

and how to be responsible for one's own actions rather than blaming others

consistently.

FJ: But we live in a society that is rooted in blaming others for their

misfortunes or mistakes?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Yes, I have been very fortunate. I practice and invite

others to practice with me.

FJ: So you have not turned away from your musical life?

JOSEPH JARMAN: No, as a matter of fact, Fred, I resigned from the Art

Ensemble in 1993 and in 1996, for those three years, '93-'96, I didn't

play or even think of music. I didn't realize it, but it actually depressed

me in many ways. I was invited by some associates to perform and so I

did and at that same time, I received the opportunity to compose a composition

and it occurred to me that I could orient that composition around Buddhist

teachings and I did and it was very successful. Since then, all of my

work, all of my music has been talking about the wonderfulness of the

way.

FJ: And future projects?

JOSEPH JARMAN: The last recording I made was called The Lifetime Visions

of the Magnificent Human and I am producing it myself and I've been waiting

for them to send it to me. I have the artwork and everything together

and sent it to the company and I am just waiting for them to get it back

to me.

FJ: What is the instrumentation of that project?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Well, it is a trio and it is a quintet. Would you like

to hear some of it?

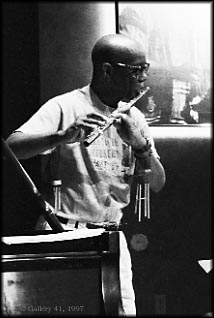

FJ: Of course. Jarman plays a fifteen plus minute composition from the

recording. It is beautiful, evocative music.

FJ: You are playing the flute on that piece.

JOSEPH JARMAN: Yes, a normal C flute. It is influenced by Middle Eastern

sounds.

FJ: What is the release date?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Hopefully, it will be distributed everywhere. It will be

distributed by North Country Distribution and hopefully it will be out

August 1. At the end of this month, July 30, I am going to Japan for a

month and I hope to have it to take some copies there with me and then

when I get back here, there will be an official release notice in the

United States in August.

FJ: Remembering Lester Bowie, how has he impacted you personally?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Oh, tremendous personally. He was wonderful. I was fortunate

enough to be with him the last week and I was working on a commission

for an English ensemble that I had been commissioned to write a composition

for and I stopped working on that composition and started working on another

called "The Passage Song for Lester B.: The Voice" and it was wonderful.

Just as I finished that composition, his son called and said that he had

made his transition an hour earlier. Throughout my life, he had always

been very inspirational to me and very giving to me, both musically, intellectually,

all kinds of levels, even suggesting that this color shirt doesn't go

with that color pants. "If you look at it you will see that there is disharmony,"

and sure enough I would change the color of the shirt and feel much better

(laughing). So, yeah, he was incredible being and it is an incredible

loss to all of us.

FJ: Seems as though you miss him?

JOSEPH JARMAN: Yes, Fred, I see him from time to time in dreams, but other

than that, I don't have the opportunity anymore.

FJ: Will you be recording "The Passage Song for Lester B.: The Voice?"

JOSEPH JARMAN: Yes, I am sure I will. I will be going to Chicago to do

a thirty year retrospective concert of my large ensemble work and I intend

to conclude with that composition.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and fuzzy naval king. Comments?

Email

Fred.