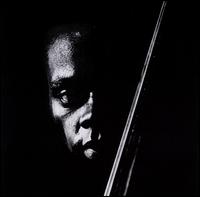

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH HENRY GRIMES

There

once was a man from Philly named Henry Grimes. After studying at Juilliard,

this bassist played alongside Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, Gil Evans, Roy

Haynes, Steve Lacy, Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, Sunny Murray, Anita O'Day,

Sonny Rollins, Pharoah Sanders, Archie Shepp, and Cecil Taylor. In 1967,

at the peak of his assent, the man disappeared. Thirty-five years later,

Grimes was found by a fan of the music living in a hotel in downtown Los

Angeles. With no bass, the call went out that Grimes expressed interest

in playing the instrument once more and William Parker answered the call.

Since, the bass player on such monumental recordings like Albert Ayler's

Spirits Rejoice, Don Cherry's Symphony for Improvisers, and Sonny Rollins'

Our Man in Jazz, has been playing the instrument he helped define for

generations of musicians in Los Angeles and New York. The journey of Henry

Grimes is an interesting one. The disappearance of Grimes is a puzzling

one. But the reemergence of Grimes is the best story to come out of music

in years. I spoke with Grimes shortly before a trip to New York, his second

since leaving in 1967. The following is my conversation (unedited and

in his own words) with a musician who defines just what a true musician

is, never failing to live a musical life, even if the music is in silence.

FRED

JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

HENRY

GRIMES: When I was younger than eighteen, I would say about twelve years

old or even before that, it was a love of swing music, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy

Dorsey. Later on, it was Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and all the quality

musicians of those schools. I knew them for years and just trying to contemplate

what they were playing just led me where I am.

FJ: Have you always played bass?

HENRY

GRIMES: No, I played violin, then I took the tuba in high school, tuba,

English horn, percussion, and then the bass.

FJ: When did you pick up the bass?

HENRY

GRIMES: Thirteen or fourteen years old in high school. First, I used to

play violin and then I switched to bass, playing in orchestras, but by

the time I got out of high school and into Juilliard, I was a bass player.

I was enrolled there for two years. The school was great. I was studying

a lot of harmony and theory writing, base studies. I took a lot of orchestra

training playing for opera singers. That I sort of enjoyed and during

that time, I played a little opera music. It was very interesting.

FJ: The violin wasn't for you?

HENRY

GRIMES: I liked it, but it just was something that I didn't like about

it. Maybe it is just that I am not a violin player. I'm a bass player,

so that must be what it is.

FJ: Why did you leave Juilliard?

HENRY

GRIMES: It was certain difficulties with financial and transportation.

I was commuting between New York and Philadelphia everyday. I just had

to give that up. Now, I am in New York again, but that was the first time

I was in New York. The second time, I was beginning to play with musicians

like Sonny Red and playing at Birdland and going through the whole scene

that way.

FJ: Philly, at that period, was a bastion for the music.

HENRY

GRIMES: I think it was as far as musicians. There were a lot of musicians

that were coming up. It wasn't so vibrant as far as getting the musicians

work and letting a lot of free expression of the music occur, but there

were a lot of musicians who did make it occur like Jimmy Garrison, John

Coltrane, and a lot of other musicians. Miles Davis and Charlie Parker

used to be somewhat familiar with Philadelphia.

FJ: How did you get the Sonny Rollins gig?

HENRY

GRIMES: About my second or third time in New York, I worked with Anita

O'Day and Gerry Mulligan's groups. I met Sonny Rollins and he enlisted

me for his group. The music was great. Sonny is a great teacher without

realizing it. The reception for the music in Europe was tremendous and

also here too. I know that when I first met Sonny, he was working with

Clifford Brown and Max Roach, their group. I sat in with them in Philadelphia

and that is how I knew him in New York after that. The reception for his

music was very great. He really knows how to play this music to crowds.

He is very good that way. There were a lot of positive things happening

for the music.

FJ: You also had a close association with free jazz cult figure Perry

Robinson, featuring him on your lone session as a leader, The Call (ESP),

as well as Robinson's Funk Dumpling (Savoy).

HENRY

GRIMES: We used to do a lot of dates at that time.

FJ: And you also did some sessions with Cecil Taylor.

HENRY

GRIMES: Oh, yeah, Cecil has always been very impressive to me. He is sort

of this wild pioneer that would sort of come up to the piano and play

more notes than there are on the piano. Musicians like that, you just

don't stand up there, you study. That is what happens when you are standing

up there playing with them, you just don't stand on the bandstand and

play music and forget about it. You have to study certain things that

you learned then and there. That is really beautiful about Cecil and other

players like that. Cecil is definitely one of my favorites.

FJ: What attracted you to free jazz?

HENRY

GRIMES: I had an idea about what free music was and so I guess having

an idea, it automatically enlists you into what a lot of free playing

musicians are. That is what happened to me. Before I could realize anything,

they were all kind of interested in what I was doing. Before I could even

recover from my own surprise, I was in with Albert Ayler, Denis Charles,

Mingus, Cecil Taylor, and on and on and on. I really enjoyed playing free

music. The freedom of expression, that was the main point with me. The

expression, you just have free will to play just what you feel. Your own

free will dictates to you to play. There were no other influences that

could override your own influences to play free music. I encourage a lot

of classical musicians to get with some jazz musicians and see what it

is to develop free music. The free music of jazz outweighs a lot of expressions

in other music because it is moving forward and ahead and it has very

much to do with free sounds and things that have never been heard before,

being done.

FJ: The Call (ESP) was you only session as a leader. Why did you not record

more?

HENRY

GRIMES: I wasn't offered too many. It is my own doing because I didn't

drag my way into a lot of musicians and writers and try to get them to

recognize me. That is the kind of feeling I had. I didn't want to be over-ego

about it. That is something that I am still struggling with and I have

to get over it. That is all there is to it. I don't seriously think that

I am not able to play. I just love playing. That is my main impulse. I

love it and when I get a chance to do it, that is the only thing that

I want to do.

FJ: In 1967, at 31, you dropped out of the scene entirely and for over

three decades, your bass remained silent. Why did you stop playing?

HENRY

GRIMES: I stopped playing in order to eyeball my own perspective better.

That had nothing to do with music. As I was waiting, it is a matter of

waiting to see if I would run into some way of musical expression like

I wanted to. It didn't happen until about thirty years or so after that.

I wasn't thinking of how long it was taking. I was just trying to gain

perspectives. It was a way of imposing self-isolation. That is the only

thing I can think of what it is. Only publically, I stopped playing. I

wrote a lot of poetry to make up for it, so I could express myself with

words instead of with music.

FJ: As an artist, you must have had yearnings to create and the poetry

helped fill the void music left behind.

HENRY

GRIMES: Oh, yeah, yeah. I was able to do it in my private environment,

no audience. I was going through experiments like that. I don't think

I am really an introvert, but I think what I really like is to try to

have more things to say and more interesting points to make.

FJ: Did you sell your bass?

HENRY

GRIMES: That is true. I sold it for the money. The only thing is, I didn't

make enough money from it. I didn't make enough money from the sale. For

one thing, it needed repairs and the repairs were expensive. I just sold

it to this violin maker and that was that.

FJ: How much did you sell it for?

HENRY

GRIMES: It was about five hundred dollars, I think. That was in 1968,

when I came down here from San Francisco to L.A. That is when I sold it.

FJ: How did you sustain yourself and make a living?

HENRY

GRIMES: I did labor work, a lot of casual labor work. I did a little construction

and a lot of janitorial work. I did both days and nights. I worked all

night. I had a graveyard shift job at a bowling alley. I would clean up

this little alley and then later on, I worked in a school, a Jewish school.

First, it was in the day time and then it was in the night time, so I

would alternate sometimes night time shifts and sometimes day time.

FJ: In the thirty some odd years, you must have heard music around you.

Did you ever feel the yearning to play again?

HENRY

GRIMES: Yeah, I think whenever I heard any and wherever I was, I think

I was studying the reaction of the people around me or imagining what

reactions they would have about the music at that time. When I really

got out of this was when I listened to some CDs of what I had done and

I had done all this in the past and that was an amazing experience.

FJ: Why did you decide the time was right for your return?

HENRY

GRIMES: When I talked to Marshall Marrotte. I didn't want to say no because

that is not the answer at all. The answer was that I wanted to play and

that's really what I like to do. There I was, but Marshall, a man of understanding,

helped me a lot with that. He still does.

FJ: Tell me about the first time you played the bass that William Parker

sent to you.

HENRY

GRIMES: I guess I went over sketches of things in my own mind of things

that I knew I had been familiar with in the past, a lot of free music,

experimenting with my reaction. I enjoyed doing this in this kind of environment.

I just gradually worked it out until it happened. I didn't forget. I couldn't

forget.

FJ: How long was it before you felt comfortable playing publicly?

HENRY

GRIMES: It takes me about three days of solid practicing. If I get in

there about three days, pretty soon, I am more and more comfortable. I

practice once during the day now, maybe about twice or three times. I

just practice different things. I have been practicing a lot of Monk and

stretching my fingers on Brilliant Corners and music like that. His harmonic

experience is pure genius. You can sit there and seek out your own experience

by his harmony and theory.

FJ: You made an appearance at this year's Vision Festival, a return to

New York.

HENRY

GRIMES: It was fantastic. That is the only way I can explain it. It was

fantastic. It was a very spiritual experience. I am going to New York

tomorrow and I think I am going to be doing more of that playing. I get

the same sense of enjoyment that I had except now, it is like, my study

is more introspective. It is really enjoyable and a pleasure. It is actually

fantastic.

FJ: Any offers to record?

HENRY

GRIMES: Yes, no definite ones yet, but the way they came forward, it is

pretty definite. I think I am going to be playing with William Parker

and musicians like Campbell and musicians like that. A lot of musicians

now play at top grade levels. There is more of them in New York, but there

are some in Los Angeles like Alex Cline and Nels Cline, the Cline brothers,

Roberto Miranda, and a lot of musicians like that.

FJ: Your return is the best thing to happen to improvised music in this

town in years.

HENRY

GRIMES: I am glad to hear you say that. It really makes me feel good.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and is Wang Chunging tonight. Comments?

Email Him