A FIRESIDE

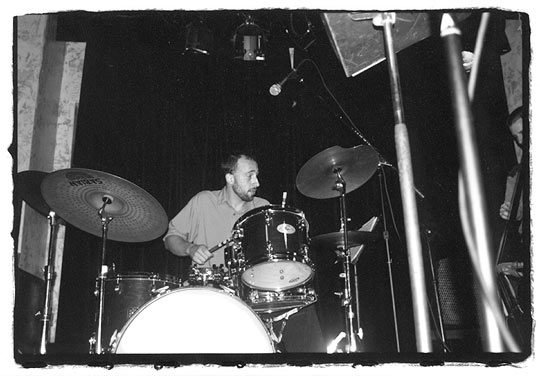

CHAT WITH HARRIS EISENSTADT

Although

Los Angeles locals barely find mention in mainstream, national media outlets

and even less in the one representing our own city, alternatives like

the LA Weekly, Wire (UK), and Signal to Noise have given amble coverage

to the region's ignored. Hope exists with legends of the past (Horace

Tapscott, John Carter, Billy Higgins, Teddy Edwards), definers of today

(Vinny Golia, Bobby Bradford, Nels Cline, Adam Rudolph, Wadada Leo Smith,

Jeff Gauthier), and the promise of tomorrow (Harris Eisenstadt, Jason

Mears, Kris Tiner, Noah Phillips). Eisenstadt, advocated by Leo Smith,

Golia, and Rudolph, is bound to push the envelope further, but whether

that is given attention is sadly left to those who chronicle the music

and not to those who play it. So in an effort to correct the wrong, Eisenstadt,

unedited and in his own words.

FRED

JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: My dad played drums and I would hear him playing along to

old rock and roll cassettes. It just seemed cool. Those were the earliest

memories, probably around five years old. By the time I was nine, I started

taking snare drum lessons. I did the concert band thing and started playing

in proverbial high school rock bands, trying to copy John Bonham and went

that route. That was long before there was any interest in anything remotely

to do with jazz.

FJ:

What motivated you to attend CalArts?

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: I had finished my undergrad and was living in New York in

'97. I was working for the Knitting Factory and stage managing one of

their venues for their jazz festival and Adam Rudolph and Yusef Lateef

were playing on the festival. I was talking with Adam about the music

and mentioned that it would be nice to go back to school again at some

point, but was lamenting that there wasn't anything around that resembled

the Creative Music Studio, Karl Berger's school in the Seventies, which

Adam had taught at. He said that Leo Smith had started a program at CalArts

and I should look him up. I got in touch and it went from there.

FJ:

How significant was your time at CalArts?

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: Leo has been very, very influential. I got there and if you

are in his program, you are thrown into a situation where you take composition

lessons from him, you play in his ensembles, you take his seminar classes,

and then you fill it in with the rest of the stuff you want to do. He

really encouraged as interdisciplinary and sort of art based in a way,

more than strictly music base in terms of approaching creativity. From

the start, it was find your own voice. Be an individual. Be an improviser,

a composer, a performer, and interpreter. Be a multifaceted and versatile

musician and at the same time, as individual a musician as possible.

FJ:

After leaving CalArts, want did you find waited for you in Los Angeles

regarding opportunities?

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: I finished in 2001 and when I came down and moved into town,

I did find it difficult as far as finding places to play, not as far as

finding people to play with. I think the first band I put together in

L.A. was with David Johnson, Scot Ray and Steuart Liebig. I had heard

Scot and Steuart in Vinny's groups. Here are these guys who had their

own voices and were part of the L.A. creative music scene. They were totally

willing to play and get involved in a project and they didn't even know

who I was. The venue thing was hard at the time and it is still hard.

I don't see that changing. It is balanced by these great, experienced

players that are willing to play with you. Vinny has been a big influence

as being a consummate individual, setting the example as someone who is

a really amazing instrumentalist, a really prolific composer, and someone

who tries to put himself in all kinds of different situations and is really

open to all kinds of different situations. Vinny is a facilitator for

the scene here. He is an advocate for a lot of people, which is really

inspiring. Leo too, Leo most so of anyone in my musical life. He was a

complete influence. There is also Adam Rudolph. He has been amazing as

a creative musician and amazing rhythm thinker. He is someone I play with

all the time and hang out with all the time and is like an older brother.

He has been generous with his time and insights.

FJ:

How did the Kreative Orchestra of Los Angeles begin?

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: I was in Gambia for two months last year studying Mandinka

drumming and my teachers had an ensemble and saw these guys working together

and was wondering what was the dynamic and through my friend, the interpreter,

it became clear that the master drummer and the "deputy" had

joined forces, each with their own band, but joined the bands together

to be the baddest group in the region. When I got back, I got to it. I

wanted to have a large ensemble, but I wanted to co-lead it. I asked my

friend, the great saxophonist and composer, Jason Mears, who I am totally

inspired by all the time because of his intensity. He is so on it and

I love what he does as a leader. We decided to do it. The logistics of

it are a total pain in the ass because to get a dozen people's schedules

together for very little bread, and for the love. As a result, Vinny is

not able to do as much stuff as he would like because of the scheduling

and logistics. Mike Vlatkovich, the great trombone player is in the band

and he lives in Portland as well as here, so he is not able to make everything

all the time. And there aren't that many places to play. All these things

make it a colossal pain in the ass, but at the same time, it is incredible

to have twelve people after three rehearsals, nailing this shit and playing

their asses off.

FJ:

Why the trip to Gambia?

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: Adam put me in touch with his old friend, the kora player

Foday Musa Suso, who lives in Gambia half the year. I was completely floored

by the music from the moment I heard it and studied it deeply. At the

same time, studying a culture's traditional music, you can never get everything,

but you can't get the essential element by not seeing it in its environment.

FJ:

You are scheduled to go into the CIMP studio with Jalolu, an interesting

quintet featuring Roy Campbell, Taylor Ho Bynum, Paul Smoker, and Andy

Laster, in late October.

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: I haven't played with that group. It is a new configuration.

It is inspired by African horn and drum music, which is very back and

forth and rhythmic and not a lot of melodic development. You hear these

horn ensembles from Africa where it is twenty guys playing horns that

have one pitch on them. It is the chorus of all these horns that makes

the interlocking melody. It is a collective horn thing with the drum ensemble.

So I sent off a recording from a gig a couple of years ago to Bob Rusch's

CIMP and he liked it and suggested I do something. It is a nice opportunity

to work with those guys. I love Paul Smoker and Roy Campbell's stuff very

much. I really dig Andy Laster as a composer and bari player. Taylor is

great. It should be fun.

FJ:

And Boxes of Water, a collective.

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: Yeah, that is very much a collective. It is Noah Phillips,

Cory Wright, Aaron Cohen. The group is a couple of years old and our first

record came out on Evander, Phillip Greenlief's label in the Bay Area.

That is a really enjoyable thing to revisit when we get together to do

that. They are good friends and nice to play with.

FJ:

You spent the better part of September in the UK and Europe, playing with

Euro improvisers John Butcher, John Russell, Phillip Wachsmann, and Biggi

Vinkeloe.

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: Yeah, the gigs with Biggi Vinkeloe, a Swedish alto player

and flutist, and Biggi is coming out of this Ayler meets Lee Konitz thing,

free, energy music, but also lyrical. That was different from my trio

gig with John Russell and John Edwards, which was raucous with Russell

ripping Cream quotes. Butcher, Wachsmann, and Tony Wren was a quiet gig

and focused and lovely. Pat Thomas was more active and had more density

to it. Depending on who you play with in L.A., you are either going to

run into someone who is more ultra-texture and minimal or just firecracking.

FJ:

So is there an L.A. sound? There is certainly one that Chicago is defining

and the loft and downtown sounds have been lauded in my time.

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: It is a tough one to wrap my head around. I think of a sound

to a lot of records that came out of 9Winds in the Eighties. Everyone

is an accomplished player technically. I do feel and this is true of New

York too, where there are a million little scenes, that whatever is going

on, it is a notoriety thing. In Chicago, Vandermark is getting notoriety,

but there is everything else that is going on as well, whether they get

any notice or not. There are a lot of great improvising, creative musicians

here, who are versatile and able to go in any direction.

FJ:

And you just finished recording with Sam Rivers.

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: It was incredible. I went to hear him play at the Jazz Bakery

and was just talking to him after. A friend of mine is his former manager.

I was just rapping with him and he asked me if there was a studio around.

I said, "Yeah," and he was like, "OK, let's hit."

This is literally what happened, Fred. He shows up at one. We hit until

four. It was amazing music. The guy is blowing circles around us. We get

done and we're sitting outside and he's like, "I have a gig, but

if you think we don't have enough, I can come back after the gig."

He wanted to come back at midnight and start recording again. It was in

Adam's studio. The next day was his eightieth birthday and he wanted to

do this. It was an incredible experience. The guy is total inspiration

as a human being. We should all be like that if we're lucky.

FJ:

And the future?

HARRIS

EISENSTADT: I know that L.A. will continue to have great music being played

and made by lots of creative people. I would hope that there is more fucking

audience. I don't know the answer to how to get more interest, how to

raise awareness of something most people don't know about, but I hope

there is just as much music being made and more recognition of it and

more opportunities for people to present stuff, more audience, and more

bread for people so they can do this shit. I don't know if that will be

the case because there is great stuff going on, but venues go in and out.

I hope L.A. has more stability as a scene so all this great music can

just blossom more.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and is Wang Chunging tonight. Comments?

Email Him