A FIRESIDE

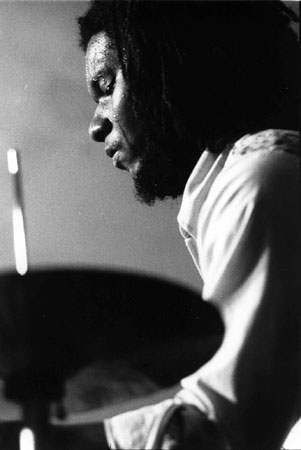

CHAT WITH HAMID DRAKE

I make

no bones about the fact that Hamid Drake is a personal favorite of mine.

But my argument is a substantial one. No other drummer has worked with

as many heavy hitters as Hamid (a list that includes Peter Brotzmann,

Fred Anderson, George Lewis, Don Cherry, Misha Mengelberg, Pharoah Sanders,

Jemeel Moondoc, William Parker, Roy Campbell, Mats Gustafsson, Ken Vandermark).

And no drummer works as much as Hamid. Han Bennink, Paal Nilssen-Love,

and Tony Oxley are killing, but my money is on Hamid. Check out both volumes

of Die Like a Dog's Little Birds Have Fast Hearts or Fred Anderson's Missing

Link classic, or the out of print, but too good to not search the ends

of the Earth, For Don Cherry record with Mats Gustafsson, or the DKV live

sessions Live in Wels & Chicago, 1998. Hamid is the poo. So it is

truly an honor to present to you, Hamid Drake, unedited and in his own

words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

HAMID

DRAKE: I would say that it was being around the family, being at home

because there was a lot of music in the home and also, my father and Fred

Anderson were really good friends. I think just from being around the

music itself, interest developed and also, when I was young, I wanted

to be in the stage band at school, in grade school. So that was the first

time that I actually started playing within the stage band. I was in the

fourth grade. So it was a combination of that, the stage band situation

and just being around the music, hearing music a lot. Both of my parents

played a lot of records and stuff. It wasn't to any particular type of

music per say, it was just that I wanted to play an instrument.

FJ: Serendipitous that you now play with Fred Anderson.

HAMID

DRAKE: They were very good friends. Yeah, I have known Fred, mostly all

my life (laughing). I have mentioned this before, but I actually wanted

to play trombone. That's the instrument that I actually wanted to play

in the stage band, but when I was in grade school, the instruments were

allotted out to the kids and so, unfortunately, there weren't any trombones

left. I wanted to be in the stage band and I had to play the only thing

was left to play which was snare drum and the big orchestral bass drum.

There was another guy and we used to switch off. Sometimes he would play

bass drum and I would play snare drum. Sometimes I would play bass drum

and he would play snare drum.

FJ: If only the music program had more funding.

HAMID

DRAKE: (Laughing) Right, yeah. Yeah, I would be playing trombone. I guess

it was destiny that it worked out that way. There was a drum teacher in

the school and at the same time, I started studying with him. That was

how it worked out. It was something that was, at first, can be viewed

as a mistake, turned into a lifetime pursuit.

FJ: How did your progression develop from drum studies to a devoted learning

of African drums?

HAMID

DRAKE: Well, actually, it was through a good friend of mine, Adam Rudolph.

We met each other in a drum shop that used to be in Chicago called Frank's

Drum Shop. We met there and he is a hand percussionist and he had been

studying congas and so he asked me if I had any interest in congas and

I said, "No." But I thought it might be a good idea to study

and he told me about a guy that he was studying with who taught in the

drum shop two doors down from Frank's Drum Shop and so I started studying

with him, with this guy that Adam had been studying with. From the interest

in the hand drums and the congas, I started to develop an interest in

other forms of hand drumming, which naturally took me to start to investigate

and appreciate the different styles of music from Africa, first starting

with hand drums. Fortunately, at that time, there was a very good record

shop also in downtown Chicago called Rose's Records and they sold music

from everywhere. At that time, it was albums of course. I started going

to Rose's Records and just looking in the record bins, first for music

from Cuba and South America. Since I was playing congas, that would be

a good place to start. I began buying records of people like Mongo Santamaria.

From there, my interest started to drift across the Atlantic to the continent

itself, to the origin of congas and various types of conga derivative

type hand drums. From there, the interest in African music developed more

and more until in 1977, Adam Rudolph, along with myself and a kora player

from the Gambia named Foday Musa Suso, we started this group called the

Mandingo Griot Society. Suso, he was a Griot and kora player from the

Gambia. From that experience, the interest developed even more and it

became more of a lived experience because now I was actually playing in

situations where there was someone from the continent who also played

a very important instrument from West Africa.

FJ: Most people couldn't tell the difference between a tenor saxophone

and an alto saxophone, how do you explain kora music?

HAMID

DRAKE: I would say that first of all, the kora is a harp type instrument

that is played in West Africa amongst Mandingo speaking people. Also,

the kora is played by a group of people that are known as Griots. Griots

are the keepers of the oral history of their various people. Griots are

not only amongst Mandingos, but amongst many different tribes in Africa.

Traditionally, the kora, amongst the Mandingo people is played by the

Griots, those who are the holders of the oral tradition. I would let them

know that the kora is a harp sounding type instrument. It is played very

much like the harp where there is two sides, the left hand is playing

one side and the right hand is playing another side.

FJ: Joe Morris and I had a conversation and he spoke about his interest

in kora music.

HAMID

DRAKE: Yeah, that is true.

FJ: Joe told me that you had one up on him, having had tea in a tent with

Alhaji Bai Konte.

HAMID

DRAKE: He is going way back. Yeah, he is going way back to the Bear Mountain

Festival (laughing) in upstate New York. That's correct, yeah. In fact,

Alhaji Bai Konte and the kora player, the Griot that we formed Mandingo

Griot Society with Foday Musa Suso, they were very good friends. Alhaji

Bai Konte was his elder of course, but still they were very good friends.

I think the time that Joe was talking about was, this was the early Eighties

when we still had some pretty good festivals going on in the States and

there was this one particular festival called the Bear Mountain Music

Festival, which pretty much centered around various types of folk music

throughout the world. It concentrated a lot on American folk music. Mandingo

Griot Society, we were on the Flying Fish label at the time, which also

concentrated a great deal on American folk music and American bluegrass,

but we happened to be on that label. Through that, we played this music

festival in Bear Mountain and that particular time that Joe was talking

about also was quite a very interesting festival because Mandingo Griot

Society, we did the festival with a slew of folk and bluegrass musicians.

Also, there was a great oud player from the Sudan by the name of Hamza

El-Din and on that particular festival also, the Sun Ra Arkestra played

too. It was quite a festival that particular year. We were all hanging

out together, Alhaji Bai Konte and his adopted son Malamini Jobarteh,

Foday Musa Suso, myself, and Adam Rudolph and the other guys from Mandingo

Griot Society.

FJ: As a percussionist who has played with so many other percussionist,

I would like to get your opinion on a few. First, Adam Rudolph.

HAMID

DRAKE: We're old time friends. We have been knowing each other and playing

music together since we were both fourteen years old. I think Adam, simply

as a percussionist, Adam is one of the greatest percussionists that I

know to tell you the truth. What he has developed on the hand drums, I

think, conceptually and playing wise is truly phenomenal. Also, Adam is

a great composer too. He has composed some very extraordinary music. It

is stuff that when you perform it, you really have to think seriously

about it because it challenges you on many levels, especially from the

rhythmic perspective. Also, Adam is a good friend. Adam and I, we are

musical buddies, but we are also life buddies. We spent a lot of time

together traveling to different parts of the world, traveling to different

parts of this country, playing in various musical situations, very diverse

musical situations with different people. I have a very high regard and

respect for Adam. He is one of those people that I have learned a lot

from and I continually learn from. Whenever we are in a musical situation

together, I feel that I always learn something from Adam and I am very

appreciative.

FJ: Tragically, Adam rarely gets the recognition he deserves because he

plays hand percussion, a lost form in improvised music.

HAMID

DRAKE: That's right. He is a multi-instrumentalist extraordinaire. Yeah.

FJ: And Michael Zerang.

HAMID

DRAKE: Michael and I have been playing together for about twelve years

now in various situations, particularly with Peter Brotzmann, but also

in duet situations. For the past twelve years now, we have been doing

in Chicago, we have been hosting these Winter Solstice concerts every

year. The phenomenal thing is that we have done it twelve years consecutively,

like non-stop every winter solstice. For the last twelve years, we have

been doing this and over the years, it has really grown and it brings

out people of diverse backgrounds and people with their children. The

phenomenal thing is that now, for the last several years, we have been

only doing early morning performances starting at six in the morning.

We still get packed houses at six in the morning of people coming to see

this music to see drums and percussions. The nice things about working

with Michael is over the years, we have had time to develop a way of communicating

with each other and really to develop our own duet style not only from

the Winter Solstice concerts that we do, but also from working together

with various ensembles, but particularly with Peter Brotzmann and the

Chicago Tentet.

FJ: You also are part of the DKV Trio.

HAMID

DRAKE: Yeah, I think Ken (Vandermark) and I started working together in

'92. The first project we did together was a project called Standards

Project and it was Ken, he was doing this project with various artists.

It just worked out that the project that Ken and I were doing was with

Kent Kessler. From doing that project, the Standards Project, it felt

like we had a nice connection, the three of us, so DKV, that was actually

the starting point of DKV. Then we started doing gigs together at a few

places around Chicago and we were doing things on a weekly basis and that

kind of formed, those were the situations that helped solidify the musical

relationship of the three of us. DKV is a situation that I really love

and appreciate a lot because the nature of how we play together allows

us to go in any direction. We have the freedom to explore many different

stylistic textures and landscapes. It is not just one particular mode

of expression, but we express a lot of different things within that group

setting. People seem to appreciate it.

FJ: And Fred Anderson.

HAMID

DRAKE: There is really, oh, I don't have a lot of words to express the

relationship with Fred other than it is definitely, it manifests in many

ways. Sometimes it is the relationship of teacher/apprentice or master/apprentice

type situation and other times, we are, I can't say equals because Fred

is my elder, so he has been around way longer than I have and he has experienced

and seen more life than I have experienced, so I can't say equal, but

I will say, we definitely share a common, we have a shared love for this

music. It is great to see when we travel to different places to see these

young audiences really being so appreciative of Fred and really digging

and understanding what he is doing. It is such a delight to see.

FJ: And Peter Brotzmann, whom you have worked with in both his Tentet

and his Die Like a Dog Quartet.

HAMID

DRAKE: Yeah, Die Like a Dog, we have the quartet, which was with William

Parker, Peter Brotzmann, and Toshinori Kondo, a trumpet player from Japan

and myself. Right now, we are mostly concentrating on the Die Like a Dog

Trio, which is William Parker, Peter, and myself. The quartet is a really

great group, but actually, it was too expensive sometimes to always bring

Kondo from Japan. He became very busy doing other projects also. Kondo

and I, we still work together in different projects with Bill Laswell

for instance. In Europe, Peter speaks about how Chicago was a new starting

place for him. Also, he speaks about how it is wonderful for him to be

a part of, and to see, and to experience this whole new generation of

people that are becoming very much into his music. Of course, some people

coming to him through knowing of his son, Casper Brotzmann, but also others

from strictly Peter himself, listening to his music, knowing his music,

and having an appreciation for his music. It is really delightful for

him to see also, this whole new group of people, young Americans that

are into his music. It is great to see that.

FJ: You are the most in demand drummer I know of, how often do you get

to sleep in your own bed?

HAMID

DRAKE: (Laughing) The last couple of years, Fred, I have been gone more

than I have been home, actually. I just returned home from touring with

David Murray because I have been working with David now for the past couple

of years. I leave tomorrow to do a couple of things with David and then

I am off to start a six day tour of Europe with William Parker and Peter

Brotzmann. Then I come home and I will be home for a little while after

that. Lately, I have been gone more than I have been home.

FJ: You are in the studio enough with others, but only have a handful

under your own name.

HAMID

DRAKE: Well, that is one of my resolutions for this year actually. I am

glad that you mentioned that. That is something that I really want to

concentrate on this year, doing more of that. It has been good for me

to work with a lot of other people and to be in a very supportive role

because that has its advantages, but one of my resolutions for this year

is to begin the process of putting more things out specifically out under

my own name.

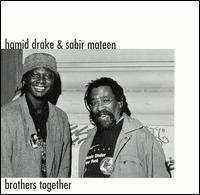

FJ: There was Brothers Together (Eremite) with Sabir Mateen.

HAMID

DRAKE: Yeah, with Sabir. He is great. Sabir, he is a great musician, a

great artist. I had heard Sabir play quite often from going to New York

and everything, but playing with him was a whole other experience. I think

he is great.

FJ: What are the various nuances between drums and frame drums?

HAMID

DRAKE: First of all, let me say that all drums are primarily string instruments

(laughing) because historically, the skins for all drums was made from

some animal part, some goat or cow or deer. Also, historically, in the

past, all strings were also made from some animal part. So drums really,

a drum head is really a large expanded string that is draped over something

just as strings in the past were gut or goat skin that was draped over

a pole. The frame drum is probably one of the oldest drums in the world.

We see it in all the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, old Greek statues

of people playing frame drums. It is basically a wooden hoop with a large

stretched string or skin draped over it. So basically, it is a string

instrument also. The frame drum is a type of, musicologists call it menbranophones.

The frame drum is one of the oldest drums in existence. The only difference

between frame drums and your modern, standard drum kit is that the modern,

standard drum kit is played with the sticks. Traditionally, most frame

drums with the exception of a few are played with the hands, skin on skin.

There are some cultures that do play frame drums with sticks, primarily

the Celtic culture from Britain. Some Native American cultures play the

frame drum with a stick or a mallet. Frame drum is just a type of, one

of the many varieties of drums that we find in existence today. Another

unique quality of the frame drum is usually when people play the frame

drum, they sing also. It is the drum that is easy to sing with. It is

the same with congas. Very seldom do you see players of the drumset singing

as they play. That doesn't seem to be a part of the tradition of drumset

playing.

FJ: Art Blakey is not breaking out in song on his Blue Note sessions.

HAMID

DRAKE: Right. It has always been part of the tradition of frame drumming

to sing as one plays and also with other types of hand drums too, the

conga and stiff like that.

FJ: Have you reached the mountaintop?

HAMID

DRAKE: Oh, no. Definitely, I don't think I have reached it and I can't

say when that might be. I think we are always experiencing hills and valleys.

Definitely, I haven't reached it and I hope I never reach it (laughing).

I always want to have room for more growth and development.

FJ: You are certainly on the hill.

HAMID

DRAKE: Thank you, Fred.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and won the Daytona 500 in a rain delay.

Comments? Email Him