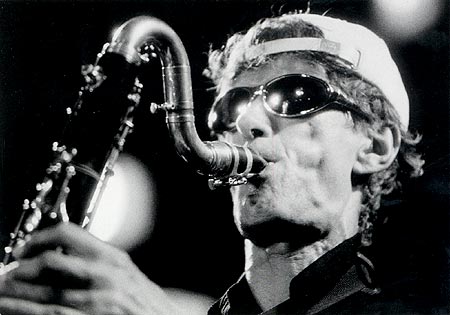

A FIRESIDE CHAT WITH GUNTER HAMPEL

My vision for Jazz Weekly has always been to promote and present artists that have little or no forum elsewhere. Down Beat, Jazziz, and Jazz Times, understandably, have to compete for the all mighty advertising dollar and a limited niche reader base that is "jazz." So musicians whose names are not Marsalis or Krall, or who are not fortunate enough to afford advertising in those magazines or have mass appeal as determined by record company executives (who in my humble opinion don't know good improvised music from a hole in the wall) of the, what is it now, one major label, fall by the wayside. And since none of us here make a dime and without a doubt, all do it for the sheer love of the music (we are losing more money than Microsoft), well, I have the luxury of presenting whomever I damn well please without any appologies. So without appologies I am always searching for musicians whose voices have not been heard in years or have not been heard at all, yet, they continue to create wonderful and vibrant works. That is true passion for the music and their passion, love, and grace inspires me. I am honored to present unto you musicians that are my heroes, that will probably never see a cover of Down Beat or Jazz Times, but who gives a shit anyway? Their music will last the sands of time and sooner or later, we will all be better for their contributions. May I present Gunter Hampel, a man of great vision and tremendous artistry, unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

GUNTER HAMPEL: I was born August 31,1937 (sign of Virgo) to Hildegard and Gotthard Hampel, in Goettingen, a little university town, not unlike Heidelberg, but right in the center of Germany. The first music I heard were the birds, the voices of my mother and father, and his piano and violin playing. When he played, the sun was shining on a rainy day. As soon as I could reach the piano keys, I was surrounding myself with all sorts of magic universes of sounds. Father, and later the piano-teacher, also discovered my talent as a composer and supported that from the beginning. Classical and folklore music was around the house. Let me mind you: there were only 78s around, no LP, CD, tape recorder, no jazz, no rock and roll, no TV, the Nazis were around and kept everything for the marching drum and the WW II (World War II). Attacking airplanes, spending hours in all kinds of basements and hear the bombs been dropped on your head, OK? That helped me to grow up fast and become aware of the survival thing. Grandpa Hampel was a composer and bandleader. He composed a lot of tunes, waltzes, marches, foxtrots and that kind of stuff, what you play on weddings. Dad had a great record collection of all sorts of classical European music. When I was seven, I added the accordion and the recorder. When I was eleven, the recorder lead to the clarinet. I actually started out with a Boehm metal clarinet. Next came the soprano saxophone at sixteen, the tenor sax and the vibraphone and later the baritone sax and all sorts of clarinets. The flute I took up so I could practice in hotel rooms on tour and compose anywhere. Back to 1945, the World War II was in its final stage. The German army retreats and the US army circles around town like the Indians in a western movie, only here with hundreds of army trucks. All army personnel, black GIs, checking if it was safe. On our backyard, there were US army trucks with campfire and soldiers and German Fraeuleins and me, eight years old and an accordion around my shoulders. I jammed with guitar-playing African-Americans, learning the first of my English vocabulary: banana, stamps, chewing gum. On the AFN (American Forces Network) Radio from the truck I heard Louis Armstrong. I didn't understand a word he is singing, but Louis talks to me. He was reaching right through to me, eager to soak up the new world.

FJ: I am curious as to your choices of instrumentations.

GUNTER HAMPEL: With the clarinet, I played the music of Jimmy Noone, Benny Goodman, or Eddie Condon style. With the vibraphone I played the music of Lionel Hampton, Terry Gibbs, Milt Jackson, Lem Whinchester, Red Norvo, Walt Dickerson, Teddy Charles, and Bobby Hutcherson. With the tenor, alto saxophone and baritone sax, I made my way through Benny Carter, Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Stan Getz, Gerry Mulligan, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy. As a composer I learned to understand the constructions of the Ellington Orchestra, Hampton, small unit inventions by the Benny Goodman Quartet, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Charlie Parker, Gerry Mulligan Quartet (pianoless), Art Blakey, Lennie Tristano, Eric Dolphy concepts. I moved through the history until I finally reached the point of now. And there was no one anymore to learn from, if you think of contemporary solutions. So I finally looked into myself and listened to what I wanted. Since I am European born and have also gone through a kind of pivotal education with my European heritage plus the jazz heritage, I started to infiltrate my jazz improvisations with the new spaces invented by Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Webern and started to improvise in a free tonal room, until then only been visited by the contemporary classical composers.

FJ: What was the European scene like when you initially started?

GUNTER HAMPEL: When I hit the music scene, there was Klaus Doldinger, Albert Mangelsdorff, Hans Koller, Jutta Hipp, and an uncountable number of historical jazz players from New Orleans style, Dixieland, swing, bebop, etc. I grew up playing all those styles. I relived the jazz history by playing it, learning how to play it.

FJ: Has the European scene changed over the years?

GUNTER HAMPEL: The German / European jazz scene still continued to copy the American stylists of jazz and until this day, that scene is still blossoming. A good and well paid and visited German jazz musician is the one who can copy someone like John Coltrane or Charlie Parker or whoever and plays to the German audiences the music that that audience wants to hear from them. I know it is not easy to copy someone and live like the original. It sometimes goes so far that those copyists dress and act like the people they copy. I think it is valuable and good to learn from other people, but if someone has the talent to improvise, they should develop that talent and speak about their own lives.

FJ: That is tremendous progress for a people and a culture. How were you able to discover jazz music and flourish within the ruins?

GUNTER HAMPEL: I could hear our favorite players and tunes, even in Germany. Let me give you the scenario: 1945 marked the end of German oppression by emperors, introduction of US democracy, new human rights, new fresh concepts to start a new way of living, the American way (whatever that means). People in charge were trying to set up a total new way of life (there is more to that, but let me just concentrate on the renewing factor), old ways out, US ways in. What it brought to us kids was what hip-hop is to the current generation: a groove, a dance, a hip way to surround yourself with the Afro-American, European merged contribution to music, and that was jazz. Rock and roll did not exist yet and the EP (45 rpm) was emerging and the 78s were our sources and the AFN and the voice of America. People like J.E. Berendt did radio shows educating us on any perspectives on jazz. French existentialism and we listened and danced to Glenn Miller, Ray Anthony, George Shearing. Tunes like "How High the Moon" and all what you call standards today sneaked into our repertoire, when we played dances. So we played as many jazz tunes as we could on these dances. Played them in 4/4. Played them as slow waltzes, as Latin sets, etc. We wrote them down from 78s. We ordered in the stores, out of catalogs, or played them by ear in all possible keys. By 1958, I was doing concert tours with my quartet or quintet, first throughout Germany, then Europe. We had nightclubs like your Blue Note or Village Vanguard or Sweet Basil, playing seven days a week jazz. One band was hired for 30 days a month! So I was traveling, one month playing in Hamburg, or Berlin, or Munich, or Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Paris, Zurich, Vienna, Madrid (Spain). We were playing from 8PM till 2, 3, 4AM every night. Other traveling jazz greats were sitting in with the Gunter Hampel Quintet: Ed Thigpen (drums), Gerry Mulligan (on alto sax!), Dizzy Gillespie (trumpet), Danny Richmond, Jackie Byard, Johnny Griffin, Milt Jackson, Don Ellis. It was a jazz circuit and we got our chops together playing year by year in those basements (we called it working down the mines - bad air, tobacco smoke and booze and prostitution, but in opposite to US clubs at those times, no pimps and no drug traffic) clean German dancing. The attraction was the band and the jitterbug dancing and the intimate moods for lovebirds. My band was performing every jazz hit of the day plus my own compositions. We played three tunes in a row and were allowed a break from no more than seven minutes in between sets. Eventually came the local radio to do a live broadcast with us from the club, or we went to the radio station's studio to do a live concert, or producers started to do jazz concerts with German bands. Until then, the concert scene was fed by producers like George Wein or Norman Granz with US bands. So guys like Klaus Doldinger or Albert Mangelsorff, Gerd Dudek, Hans Koller and myself were starting to get nationally and internationally known as some "white" European strong jazz voices. Jazz was starting to spread around the globe. Louis Armstrong was touring all over the world with his all-stars and kept turning people (like me) on to jazz. We soon learned, that there was a different message between the American way of life and the message, which is in jazz. Jazz was everywhere in those days, in the clubs, on the radio, the blue jeans and the Johnnie Walker. US Army clubs had us playing for floorshows, entertainment and dance. And one other thing: the music got appreciated for its ingenuity. To be a jazz musician or a classical musician was an honorable profession with respect from society. It was (and is) human expression on its highest level, witness to the human evolution, a way of life.

FJ: Strange how that highest form of human expression is practically ignored within the country of its birth.

GUNTER HAMPEL: There were no racial or musically prejudices with those remarkable musicians, poets, writers, philosophers, doctors, lawyers, or just plain people among jazz fans all over the world. Besides being very particular about what styles of jazz they like and what not. One can say that jazz fans' hospitality and vibrations are more human. Maybe the steady expose to this great music is forming a good character. Since I live in NYC since 1969, I have some oversight of both, European and US. Since the invention of the CD (which will soon be replaced by the DVD) some strange stuff has happened to jazz. I remember back in 1987, '88, there was a time when the LP disappeared out of the stores and were replaced by CDs. All of the sudden my whole line of LPs were taking out of circulation and I was no more present in the stores. That was the time when something very crucial happened to jazz, happened to us jazz musicians. It was already very, very difficult to get recorded by a record company in those days, but the major companies stopped recording contemporary or young or old musicians. Instead they were re-publishing the music out of their vaults on CD. Sure, they had that stuff sitting in their archives and they could save money in not recording new guys anymore. And that left a whole new generation out of being recorded, of being recognized, of being able to make a living as a jazz musician. Such brilliance wasted. Instead of correcting that picture, big business was again boycotting creativity. Instead of allowing new venues they popularized the concept of the jazz standards. With the rise of jazz schools and teaching jobs for jazz musicians at colleges, jazz is more and more becoming a repertoire music. The jazz business and the record companies rather indulge in remakes, having young talented musicians being involved in recording another version of a jazz standard in the same style like the ones, which are selling good from their tapes from the vault. They rerecord the whole jazz history all over again with young cats. Among many other aspects this makes it unattractive for young, upcoming musicians, because they see and hear what is being done to their generation. It is a very frustrating process. The business has taken over and is killing the cow they want to milk. So, that is what is happening in the US and in Europe, in Japan, is happening all over the world. The mass media control is only allowing that much creativity, which still sells. It is cutting off the needs of expression for new generations, which have to and should find their own identity. Jazz has enough resources.

FJ: But there are other means of expressions that seem to have captured the ears and imaginations of the youth.

GUNTER HAMPEL: Jazz is the mother of all the offspring like rock and roll, hip-hop, pop, boy groups, techno, and what have you. They all use the drum set and a bass. Any of this popular music is a child of jazz. The drum set in its today set up has been put together by jazz masters, from Baby Dodds, Zutty Singleton, Kenny Clarke, Max Roach, Billy Higgins, Elvin Jones, Steve McCall. The bass playing had been added to the jazz rhythm section by Jimmy Blanton, Oscar Pettiford, Ray Brown, Charles Mingus, Leroy Vinnegar, Scott Lafaro, Jaco Pastorius, etc. So I am not really blaming the industrial corporations for wanting to make a quick buck and I can already hear the many good people working the record companies for releasing all this incredible documentary stuff from their vaults and how hard and difficult it is to at least get them to the point, that invaluable gems of music can see the light of publishing this way, but this only way of thinking has turned off the kids to jazz. They feel uncomfortable with the idea of having to listen to Charlie Parker. Let them discover Parker. Current generation kids have a total different set up with the world of the internet, computer games and rap and hip-hop around them.

FJ: So how should the industry go about reaching out to the youth?

GUNTER HAMPEL: You do not get through to them by throwing two million dollars in researches to jazz professors who are writing off from records note by note, including the improvisations of the soloists from old Count Basie records. Use that money to record new artists who deserve that. Every generation is generating the same amount of jazz geniuses to nourish the jazz continuum. Find them and keep the natural flow of renewal intact. I will tell you how I do it. Last year I had a big band workshop with my charts, going to Dessau, a small town in East Germany. I was to rehearse, train and perform with two youth big bands for three days. One big band was ages sixteen and up and one big band ages twelve to sixteen. In order to get more effective, I threw both bands together and had a full sized orchestra with eight trumpets, ten or more saxes, eight bones, and two rhythm sections. They usually play those printed arrangements with the solos all written out. So these kids in East Germany, age twelve to twenty-four played Count Basie. They are trying the impossible, to re-feel, remake the Kansas City groove in a total after-Russian occupancy society. Sure, they learn something from the old masters this way, but it isn't their field of living. They goof here and there and feel terrible because they are totally being asked too much of them. They did not look happy after all. When we played my stuff, with its many sections of collective improvisations, of horn sections leaving lots of room for creative action and reaction within the big band textures, the kids got engaged and played after some days really great because they love to be involved with everything they got. There was a twelve-year-old alto saxophonist who really had a nice tone, execution and what have you. I interviewed him, "Who are your idols?" The twelve-year-old said, "Ben Wester, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Johnny Hodges." Folks, jazz is not dead. Jazz is alive. Let's work on it to keep it that way.

FJ: In Germany, much of the events and artists have government subsidies, whereas in the States, the only thing the government seems to subsidize is independent counsel probes of our President.

GUNTER HAMPEL: In Germany, most clubs have closed or play happy salsa nights. When you want to play there, it is for the door, or sixty percent from the door. If there is a jazz concert in the club, there come between fifteen to sixty people to attend it. Not enough to pay for the band and the club owner. The only jazz tours are done by bands from large record companies like ECM, Sony (Columbia), because they control the market to, who knows, ninety-nine point nine percent. They determine what the media is allowing the people to hear, naturally only their own products and artists. Kids are today being programmed by MTV and the mass media. Television is bringing almost no jazz and when it is, it is the most watered down, commercial remake of a remake of a remake. To present jazz, we probably have to set up our own TV jazz station. The hope that the internet could change something is very small. Jazz sales through the internet are still very, very slow. There is not a jazz musician who is not frustrated about this situation. The only time when there is jazz with its full spectrum is at the jazz festivals. It hasn't been like that, until very recently. When we started out, what is been called now the free jazz thing in Germany in the Sixties, we had a large crowd attending our concerts because we were breaking away from the standards. I had enough of playing "All the Things You Are" and for the thousands time "Lullaby of Birdland." It was nice to do that, playing those great American tunes, but that was not my life, to re-feel Broadway tunes from musicals. When Louis Armstrong played, it was his life, his tunes. Copying is for learning, but not spending your whole life with it. I played with a lot of African-Americans in the Sixties, who talked Africa, Africa, Africa all day, wore colored African shirts and made it look like jazz was only a dissension out of Africa. Well, I am not African. I am European. Whatever that means. I think of myself as a being, living on Earth for the moment in a human body, amazed of what is going down here. But anyway, I also know that jazz is a merge of Africa and Europe. Coming together in the USA (supposedly in New Orleans, the cotton fields etc.). But what happened was, that the pentatonic African scales and the polyphonic rhythms (Africans do not count off) met with the well-tempered clavier, twelve tone tuning within an octave of the European music. African-Americans played the piano, trombone, trumpet, clarinet, saxophones, tubas, bass and string instruments like the guitar and started out with little folk tunes based on German, French, Italian, etc. Folksongs like a four, eight, twelve, sixteen, thirty-two bar tune. So the Africanisms of my fellow American jazz musicians made me get closer to my European bonds and I learned to appreciate my own heritage. I went to study with German contemporary music teachers in music high schools or even had the chance to perform with classical composers like Hans Werner Henze (LP on Deutsche Grammophone) or Christoph Penderecki (Phillips, opposite a Don Cherry suite) learned with Professor Wolfgang Fortner or Stockhausen decedents like Konrad Boehmer or when I was in Holland, Willem Breuker took me to perform with him in Louis Andriessen's piece at the concertgebouw in Amsterdam. I recorded with Hans Werner Henze in Rome in Italy back in 1971. When I met Jeanne Lee or Marion Brown or Anthony Braxton or Steve McCall, and we played my compositions together, in which I leave lots of space for any performer to bring out the best and make them and us play at the outmost level of energy and consciousness together, I believe we are re-continuing the progress of original jazz making. African and European meet again in this time to renew a birth of original music. This fact made me set up my own record label Birth to document this unique concept. So with us, that is the original masters - or as Steve McCall expressed it, "The Champs," hooking up and play in the major leagues in Europe as well as in the US, there was something growing over the years, which is now called the new music. The importance of a jazz musician being allowed to be an artist, let's say, like a painter who paints a picture as he sees it and not the agent who sells it. A writer who writes about what he feels to write about. Why does a jazz musician not have the same rights? Because in the USA your compositions are not protected. You do not get money from airplay. I am fighting since 35 years with the ASCAP to get my rightful royalties from airplay and no result. I have my music sometimes played by three hundred and fifty NPR radio stations all over the country. So back to your question, in Europe the awareness about the possibility to invent your own music within the frame of jazz is probably more around than in the USA these days. The spectrum of what jazz is in the USA is hindered by the imagination. Jazz is entertainment. It is the best entertainment there is, but it is more. European classical music is a force. It has inner powers, energies, spiritual strength, inner peace, insights into human nature and a magic of its own, expanding human consciousness. Now we have reached a moment in time where jazz has the same to offer. Some say it is food for the soul. We say it makes you think. It helps you to get yourself together. We, the musicians actually do not need to know all about this. We need to rehearse, train, perform, record and expand our knowledge, learn how to stay healthy and in form like a basketball player, meet other great players and to perform together. Up till now, we had the audiences. The industry has been taking them away from us. The jazz communities do not have the cash to counteract the crime and stupid-ness which comes with mass media products. The controlled society has already been established, Matrix, Enemy of the State (motion pictures). But, we also have the improvised scene in Europe. My band with Schoof, Schlippenbach, Niebergall and Courbois, we had started something: the first sign of an improvised music, jazz as a European style. Jazz had gone outside the US and found in us young musicians willing to put our lives out on a limb. I mean, they could not kill us for playing our own music but, and you have to believe me, some would have loved to try that. I remember scenes where people took my mallets out of my hands, while we were playing, took the drummer's sticks away, banged the wooden piano lid on Schlippenbach's fingers and tried to put a broken beer bottle in Breuker's face. I had anonymous phone calls, if I wouldn't stop playing that music, I would get killed etc.

FJ: That kind of dedication is what brings about fundamental change, which you must be credited with.

GUNTER HAMPEL: Well, today we have about four hundred improvising new music players in Germany and have faculties in Koln, Hannover, Hamburg, Leipzig, Berlin, Munich and other towns, where you can study jazz at the universities to become a jazz musician. Jazz or even our "free jazz" as the world calls it (Free from what?) is a well-respected art form. I got a money price from the governor of Lower Saxon (he is now our Bundeskanzler, G. Schroeder), who gave me the honorable price, otherwise only given to politicians, inventors, writers, etc. because of my jazz inventions and my carrying this German invention all over the world. Fact is, that I have made a personal contributions to the ways of playing music together. If that is European or US, I do not know. I know, I have taken what was there and have added another dimension, another way of doing to it because I was missing that space in which to play the things I and my team's expressions of now, of our own time zone. I believe in the fact that each generation is manifesting its own thoughts, music, because we all have different life conditions. In the old times, in Europe, the forces in power were the church and the governments always fighting for the main power. Today the industry has taken over and church and governments seem to be following the orders of industries all over the world. The industry is taking care of us. So today we have musicians, who play what the industry dictates and we have musicians who speak their inner truth. Make your choice.

FJ: You have been leading your own band for almost half a century and would be legendary if you had spent those years in New York. Why did you not move to New York and do you regret not doing so?

GUNTER HAMPEL: I moved to NYC in 1969, still touring in Europe every year, several months. The fact is that the USA does not provide enough paid work for me. To some people the term legendary has been attributed to my work.

FJ: Is the advanced improvised music that is being played by Europeans outpacing the growth in their American counterparts?

GUNTER HAMPEL: I think, from my observations, in Europe, we have a German, English, Dutch, French, Italian, etc. Jazz scene in the US we have a black and a white (mostly Jewish) jazz scene. Marion Brown once told me that the German, Italian and Jewish people have the most talent to feel and play jazz. But Marion meant that these cultures had the most talent to copy African-American jazz. That was in the beginning. Now people from other cultures, like me, have taken jazz further down the road. And I know of talents in every culture on Earth. To me, jazz is such a universal language, as it was in the very beginning. The picture is that jazz emerged out of the meeting of Africa and Europe in the US (New Orleans etc.). Rhythms and musically concepts from Africa were meeting the European instruments and song forms in New Orleans. Africans knew then five notes in an octave. People like Johann Sebastian Bach had "invented" (discovered) twelve notes in an octave. So, there you have it. And the four, eight, twelve, sixteen, thirty-two bars for a composition came out of German and French song forms. Europe and USA is not outpacing each other. We grow together because we all live on spaceship Earth.

FJ: Let's touch on your collaborations with Marion Brown.

GUNTER HAMPEL: We met in 1967 and played together until 1994. In the liner notes to our duo CD, Gemini, I am writing some pages on our collaboration through all these years. We called our duo CD Gemini because after all those years we felt like twins as different as we could be, Marion born in Atlanta, Georgia and me born in Germany, Goettingen. Our conversations could fill up another book. Our music probably still rings in the universe. The glory of playing together, the celebration of "interracial" music creation, as different as we are, as life made us to be, is still considered to be a highlight of African-American and European music collaborations.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and is the superfly weight, middle weight champion of the world. Comments? Email Fred.