A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH GEORGE COLEMAN

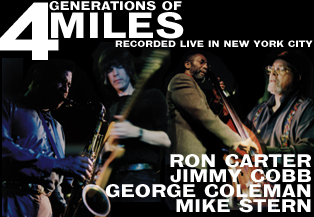

It

must be a difficult cross to bear to be known mostly for leaving Miles

Davis. After all, George Coleman is credited with departing what is jazz's

most famous quintet (Miles, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, Ron Carter,

and Wayne Shorter, who filled the tenor seat after Coleman). Difficult

cross. My daddy always told me that the depths of a man's character lay

not in his victories, but in his defeats and admirably, Coleman has served

himself well. Critics have the memory of elephants and I don't have much

hope they will get the whole Miles thing go. Coleman ought to be recognized

for his own work, which is pretty impressive. If in doubt, just keep in

mind that Miles did ask him to be in his band and Miles had one hell of

a musical eye. I spoke with the tenor about his relationship with Miles

and 4 Generations of Miles, a new release that is self explanatory, as

always unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: I began listening to the music at an early age. I was in my early

teens when I first began to hear it, somewhere around fifteen, sixteen

years old. Shortly after that, I began to get interested in playing an

instrument, which was the alto saxophone and that was mainly because of

Charlie Parker because he was my inspiration. He was unique. All that

I heard of the instrument was Louis Jordan and Earl Bostic and some of

those R&B players, who I admired tremendously. Charlie Parker was

the real deal. He was the man I was really inspired by. His great technique

sound and all of those great qualities is what interested me in playing

the music. And after that, of course, I heard so many other great players,

Sonny Stitt, Sonny Rollins, and people of that caliber.

FJ: Where were you when Bird died?

GEORGE

COLEMAN: As a matter of fact, I just went on the road with B.B. King in

1955. When I arrived in Houston. I traveled from, my first plane trip

incidentally, from Memphis, Tennessee to Houston, Texas. When I arrived

in Houston, a few days later, I found out that he had passed, somewhere

around March 13 or early March, close to my birthday, which is March 8.

I remember that quite explicitly.

FJ: Was it long after you made the switch from alto to tenor?

GEORGE

COLEMAN: I made that switch when I joined B.B. in 1955. When I arrived

on the scene, he went to the music store and bought me a tenor and that's

when I began playing tenor because he had an alto player in the band.

He needed a tenor player, so he wanted me to play tenor, so that's when

I made the switch. It was different, but not difficult because I was pretty

much familiar with the saxophone and I had picked up a tenor probably

once or twice before that, but I had never really played it that much.

FJ: Your thoughts on your time with B.B. King.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: He wasn't at the height then. He's at the height of his career

now (laughing), with all the acclaim he is getting now. But during that

time, he was popular though and he was popular all over the United States,

north, south, east and west. That is where we traveled in the years time

I was with him. I was with him probably no more than a little over a year.

That year, we went throughout the United States, north, south, east, west.

We came to New York and Detroit in the East and of course, down South,

we went to all the southern states, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina,

and a lot of Texas because the booking agency was located in Houston and

that was like our home base, Houston, Texas. Whenever we weren't working,

we'd be there.

FJ: But you moved on.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: Well, it was time to go because I knew I didn't really want to

be an exclusively R&B player. It was just one of the things I had

to do to make a living during that time. It was a good experience.

FJ: When was the "golden age of jazz?"

GEORGE

COLEMAN: The golden age of jazz was in the late Fifties, middle Fifties,

or throughout the Sixties. That was really the golden age because there

was so many great records produced during that time, Charlie Parker with

Strings, the Dizzy Gillespie stuff. Of course, you could go back further

than that because it really starts in the Forties when you had Dizzy and

the big band. That was really the dawning of it, of jazz as the bebop

era so to speak, which is a very important era because that was the foundation.

Now back in the Twenties, you had Dixieland and that type of thing and

you had Scott Joplin and some of the old boogie-woogie piano players of

that era playing great stuff and Count Basie back in the Thirties. So

it goes back. It goes back, but it started somewhere around early Thirties,

late Twenties, that's when it really began to take hold, but when you

start talking about the so called modern era or mainstream or bebop or

whatever you want to call it, which was really the era, I think, that

was much more important for jazz, but it was all important. Even the Dixieland

era in the Twenties and Thirties, throughout the Thirties, all of those,

those times were important. But I cite the Sixties, the late Fifties and

the Sixties because that was the era in which I came up in, which was

a very important era because there was so many different, great players

that you could listen to during that time and formulate a style or a concept

of whatever you needed.

FJ: How was your maturation?

GEORGE

COLEMAN: Listening to records. As I said, the people that I listened to

during that time, Charlie Parker, transcribing his solos, and others,

that formulated a good technique. The real deal was when I began to play

with the masters, say like Max Roach. I had a pretty good technique before

I left Memphis though actually. I was in pretty good shape because I had

done a lot of practicing. But if look at the history of my development

as a jazz musician, the span is about thirteen years, from the time I

picked up a horn until I reached the zenith of my career, which was with

Miles Davis. So you think about when I picked up the horn when I was about

sixteen, seventeen years old, just out of high school and immediately

after that, but you figure '53, '54, '55. Now '55 was when I made my first

major band, B.B. King, but in that time, so that's only three, four, I

would say tops four years, I was a professional, getting ready to go on

the road with a band and had basically all the tools required. I could

read a little bit. I could write arrangements. I had formulated a pretty

good technique. So that was in the Fifties, middle Fifties, '55. Then

after that, '56, when I went to Chicago and started sitting in with great

players like Gene Ammons and Johnny Griffin, Sonny Stitt and people of

that caliber, that was another level. So when I left Chicago in 1958 to

join Max Roach, that was another milestone. That was another steppingstone.

So you can see from when I first picked up a horn back in the early Fifties,

maybe '51, '53 up until '58, that's about six years and here I am with

the top band. Then in the Sixties, 1963, I could go no higher than Miles

Davis. So when I joined him in 1963, so you figure there it is, that about

ten years right there. So from the time I picked up a horn, I would say

between ten and thirteen years, I had reached a zenith. I had never really

thought of it, but when you look at that, Fred, after thirteen years,

you went from just picking up a horn to the top in thirteen years. So

that was quite an accomplishment, but I had never realized that until

recently. I found out that that was it, in that short span of time. Sometimes

it takes guys twenty, thirty years to maybe reach the plateau that I had

reached. I had went from just starting to the upper crust, to the highest

level you can obtain as far as a sideman is concerned.

FJ: Tell me about Miles.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: Well, one night, they were playing in New York with that famous

band, John Coltrane, I think Wynton Kelly was playing piano, Paul Chambers

was on bass, John Coltrane was playing saxophone, and one night, I came

down to sit in with the band. I just felt like I wanted to play with the

band and I had no horn. But John Coltrane was gracious enough to let me

use his instrument, mouthpiece and all. So I sat in with that band that

night, played one or two tunes, one I remember explicitly. It was "Lover"

and it was a little brisk too. It was up-tempo. I must have impressed

him because a few months after that, when Trane left, I don't know how

long it was after that, that he was with the band, but shortly after he

left and then Hank Mobley joined the band, so I would say, maybe close

to a year after that, I was called. Somebody called me. He didn't call

me, but somebody called me and said, "Look, Miles wants you to call

him. He's in Philadelphia. Give him a call," but I never called him.

I didn't feel like I was ready. So then, one time after that, maybe a

year after that, I'd say probably a year after that, we're talking Fifties.

This was after I left Max because I was only with Max Roach for a year

or two. So about '58, '59, just tip of '59 and I left his band. This happened

around 1959 when I sat in with Miles. Anyway around '61, '62 because I

was playing with Slide Hampton's octet during that time, gaining experience

writing and playing and all of those things. Around, somewhere around

'62, '61 maybe, I got a call from those people that told me to all him,

which I never did. So 1963 was when he called me in person. He said, "I'd

like for you to come to Japan and do you have any other people you might

want to recommend because I'm getting a new band." I recommended

Harold Mabern, my partner from Memphis, for the piano. He needed a piano.

He wanted another horn besides myself, so I recommend Frank Stozier, who

played alto. So when we first started out, it was a sextet, alto, tenor,

and him on trumpet. It was three horns and Harold Mabern on piano, Jimmy

Cobb on drums, and Ron Carter on bass. So that was what the sextet was.

That lasted for a few months and we toured the West Coast. And then, after

we finished the West Coast, he condensed the band. He broke it down and

said that he just wanted a quintet. Jimmy Cobb left and I was the only

remaining piece of that puzzle. Me, along with Ron Carter, we were the

only two left in that band. That is when he added Tony Williams and Herbie

Hancock and then the rest is history, the famous Miles Davis Quintet that

made all those records that people still talk about today, My Funny Valentine,

Four & More, Miles Davis in Europe, and Seven Steps to Heaven. It

was those four albums that I did with him during that period, in just

a year. In 1963, we did four albums. Of course, these albums were probably

released in the latter years, maybe a year later because most of it was

done live. The only thing we did in the studio was Seven Steps to Heaven,

but all the other stuff was live, My Funny Valentine, that was Lincoln

Center. Four & More, that was Lincoln Center and Miles Davis in Europe,

that was in Antibes. You had three live recordings that were classics

in the minds of some people. That was it. I did four albums with him in

that short span of time, a little over a year.

FJ: Seven Steps to Heaven had a unique lineup, Herbie Hancock and Vic

Feldman sharing piano duties.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: Yeah, so it was a compilation. What happened, Fred, was it was

a quartet with Frank Butler on drums and the piano player, what was his

name?

FJ: Vic Feldman.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: Yeah, yeah, it was Vic. Victor Feldman. It was just quartet things.

It was about three or four quartet things, ballads that he played and

then, "So Near, So Far," "Seven Steps to Heaven,"

was a quintet, maybe "Joshua" too. I think we might have did

"Joshua" on that one. So it was three quintets and three quartet

things with Vic Feldman, Ron and Frank Butler playing drums. So that was

just put together. Seven Steps was part in California and part in New

York. Our segment, the quintet segment was recorded in New York.

FJ: Why did you leave the band?

GEORGE

COLEMAN: The major reason was, during that time, Miles was not in good

health. I would wind up being out front, standing out front and in a quartet

situation because a lot of times he wouldn't show and then people would

think I was Miles Davis. You can believe that. That is an absolute fact.

They would come to me after the set was over and say, "Oh, Mr. Davis,

the music was so tremendous." They had never seen Miles. They didn't

know what he played, but he was so charismatic that even if he wasn't

there, people thought he was. They didn't know whether he played tenor

or trumpet or what. So there was too much pressure on me. It was a lot

of pressure. That was one of the major reasons. There was a couple of

other little things that was not as quite as important as that. That was

the thing that made things pretty difficult for me, having to stand up

front masquerading as him unintentionally of course, but that's the way

it was. I was out front and then there was a little bit of, I wouldn't

say jealousy, but some of the other members in the band, they were trying

to go in another direction. Me being out front was sort of stymied their

thing that they were trying to do, the other components in the band. They

were trying to play too hip. They were the young breed, Herbie Hancock,

Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. So I was the old fashioned guy in the band.

So I was in a sense, in a sense, I was ostracized. I was trying to play

the book. I was trying to play the stuff that he played when he was there,

"Bye Bye Blackbird," "Autumn Leaves," and stuff like

that, "So What," all those kinds of things, but they wanted

to go out and play what they thought was the hip stuff. So I was somewhat

of an old fashioned, they used to make fun of me, until one night, he

was off the stand and he kicked off a fast blues and he left the stand.

He went to the bar to drink his usual champagne. So it left me up there

and this particular night, I had gotten a little bit tired of them turning

up their nose at me and I knew what was going on and so I was just going

to show these guys that they are not so hip after all and I can play this

stuff that they're trying to play and so I started playing some real out

stuff, really out stuff, but it was swinging because they were swinging.

So I fell right into their little thing that they were trying to do and

when he heard this, he was at the bar and he rushed up to the bandstand

and said, "What the hell was that?" He was as surprised as they

were and from then on, they knew that I could play with all this stuff

that they had been talking about trying to play. So they kind of got off

my back a little bit behind that. Strangely enough, after that incident

happened, I went right on back to my bebop that I had been playing all

the time, changes and all because I love to play changes. It was illustrating

a point to them to show them that I could play that stuff that they were

trying to get to. It proved a point and that is all in the book. That

is documented in his book about that particular incident. He didn't really

know that I could play that out himself because I had never played that

out. He said I was always the perfect player on the harmonics. He said,

"George was always playing perfect stuff." It was harmonic changes.

We're talking about changes. I was always talking about changes. I wasn't

talking about that far out stuff, which I could do and incidentally, on

some stuff that we recorded, I stretched out and I played a little bit

on the outside, a little bit, not a lot.

FJ: Ironically, you are out front once more on 4 Generations of Miles.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: Oh yeah, it seems that I got pushed out front again. That is

one of the things, if you're a horn and you're playing in a rhythm section,

it could be vibes, it could be piano, it could be guitar, but if you are

standing out front with a horn in your hand, it is almost assumed that

you're out front, that you're the leader. So whether you like it or not,

or whether you feel like you shouldn't be out there or whatever, it happens

anyway. So that is just one of those things that happened. It is not a

thing that I dislike because I've been doing that all my life, especially

since recently when I've led my own groups, I've stood out front as a

leader. As a leader, that's what you've got to do. You've got to stand

out front. But that is one of the situations that when you find yourself

in that situation, you have to respond and play like you're standing out

front. That is the only way I can play.

FJ: Playing with Ron Carter and Jimmy Cobb is old hat for you, but it

was your first time playing with guitarist Mike Stern.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: Oh yeah, that was the first time with Mike. To me honest and

frank with you, Fred, it was a little bit out of character from what I

normally like to play with. I always like the keyboard. Now, if we had

a keyboard in there, I think it would have been much more suitable for

me, but since it was a quartet and the only person playing any kind of

chords and he wasn't playing that much to say you the truth. He didn't

give up too much accompaniment. It was almost like I was playing with

a trio to tell you the truth in some instances, to be honest and frank

with you. It worked out and he's a good player. He's a young player. There

were some things that we tried to get him involved in, but it was spur

of the moment stuff. You can't get certain things overnight. But under

the circumstances, I thought he did quite well. His solos were good, but

that wah-wah effect on the guitar was a little bit out of character for

me as far as what I like to hear.

FJ: So you would have preferred Harold Mabern.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: I would have preferred Harold Mabern or some other keyboardist.

Harold Mabern would have probably been perfect because he would have anchored

everything and give us that real meat that we needed and if Mike had been

there along with that, it probably would have enhanced it even more. That

is one of those things. That is all history now, so we have to deal with

it the way it is. Upon a listening, it came off pretty good. It makes

you stronger when you're in a situation like that and you've got to put

your best foot forward so to speak. If you're a performer or musician,

whatever instrument you're playing, you've got to have creativity, good

technique, and harmony, those three things is what goes with the music.

Some guys may have one or two, but when you've got all three, that makes

for a good performer.

FJ: You played high school ball.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: Yeah, that was years ago, yeah. I was sidetracked by the music.

Any glimmer of hope for that was negated by the music that I was hearing

from Charlie Parker and some of the other great players. So I knew right

then that I wanted to be a musician pretty quick and not an athlete.

FJ: What position?

GEORGE

COLEMAN: I played linebacker and I was an offensive end because back in

those days, in high school, you go both ways, defense and offense.

FJ: Raiders need a good linebacker.

GEORGE

COLEMAN: (Laughing) Yeah.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and is curious why the religious nuts

didn't come out and protest all the

dope references in Scooby Doo.Comments? Email

Him