A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH GATO BARBIERI

A handful

of years ago, I was turned onto a Don Cherry record, Symphony for Improvisers.

The energy was palpable. Playing alongside avant heroes Cherry and Pharoah

Sanders, to me a little known Gato Barbieri outshined both. Subsequently,

releases on ESP (In Search of the Mystery) and Flying Dutchman (The Third

World, Fenix) have allowed me to gain further appreciation for the Argentinean

tenor. Held responsible for more recent commercial sessions, people forget

the sheer aggressiveness of Barbieri's days of old. Never forget folks.

There are reasons and I asked Barbieri for them. Barbieri spoke with me

from his home in New York and as we talked about his childhood, his road

most taken away from free jazz, and his love for his late wife, I began

to gain an even greater appreciation for the man behind the music. Even

with the language challenges, Barbieri spoke eloquently about his life,

as always, unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

GATO

BARBIERI: In Argentina, we played jazz in 1950 very good. My uncle, he

played tenor. My brother, he played trumpet. We played bebop when I was

seventeen. I played classic music. I played Stravinsky. I go to the city

and I have knowledge of almost everything about the music. I play jazz.

It was being a little rebellion, no? Rebel.

FJ: You were a rebel.

GATO

BARBIERI: In some way, yeah. But I like jazz. Few records we have because

in those days, never come anything. But when I was twelve, I buy a record

of Charlie Parker and for me, it was, it opened something. I understand

immediately. Some people, it takes years and years to understand. For

me, it was very right on the button.

FJ: What was it about Bird?

GATO

BARBIERI: Everything. I liked Benny Goodman. I liked more Harry James.

In fact, Miles Davis said one day that Harry James was incredible trumpet

player, but he don't have the courage to go ahead because he was in Hollywood.

But Parker, we have one record every one year. We don't have instruments.

We don't have anything. You have to imagine the things. For me, when this

record comes, one was with Dizzy called Anthropology. It was incredible.

For me, it was something so natural. This is what I like in those days.

FJ: When did you make the switch from alto to tenor?

GATO

BARBIERI: When I listened to John Coltrane. I had to go to Uruguay because

Uruguay in those days, after the war was a little rich because a lot of

people from Europe with money there. So we have record, everything, instruments,

and I listen to Round About Midnight and this for me, he was the successor

of Charlie Parker because he had the same feeling. Obviously, he play

different, but he had the same something you can have. You can't learn.

You have it or you don't have it. So for me, Coltrane, he helped a lot

Miles Davis because until Miles, never have, he switched so many things.

He played cool with Lee Konitz. He played West Coast and this and that,

but when he played with John Coltrane, he said John Coltrane was the key

to grow with this group and after, Miles did all the things. Parker, he

did so many things, but he died early, thirty-six years old. For me, Jaco

Pastorious at twenty, he already had his style and he died thirty-six

like Charlie Parker. So what I say, for me, music is a very mysterious

thing, especially, in our music. Some people, they don't know anything,

but they have incredible mentality or feeling. Some people, they study

technically and move his finger, but this was not before. Before a musician

was more natural. Now people want to have technique and I don't know.

It changed. The music for Charlie Parker and all these people, even Ornette

Coleman, they was natural. They blow. Now, they want to experiment.

FJ: You recorded some blowing albums of your own in the Sixties.

GATO

BARBIERI: Yeah, well, I played, I got to say, I played classic. I play

with Don Cherry, free jazz for two years. After I did with ESP, I played

with Jazz Composer Orchestra, Michael Mantler, who was the cousin of Carla

Bley. I did so many things, but at one point I understand free jazz not

was my style.

FJ: You were damn good at it.

GATO

BARBIERI: Well, it doesn't fit. I follow the other people. When I did

The Third World (Flying Dutchman reissued on BMG International), that

was Gato Barbieri. I did something incredible and the same for instance,

here, it doesn't have much impact, but in France, they was considered

the best album of the year, 1969. Slowly, free jazz is starting to disappear

here. I don't see connection, so I met Glauber Rocha, a filmmaker from

Brazil. He died. He made incredible films (Deus e o Diabo na Terra do

Sol) and even Bernardo (Bernardo Bertolucci, Barbieri scored Bertolucci's

Last Tango in Paris) and he said, "You are Latin," so in 1969,

I go to Buenos Aires and I did a show. It is the first time I made money

where I played tangos, Brazilian music, Cuban music, everything. It was

like a cocktail of fruit, no salsa. I don't play salsa. I play what I

call salsa of fruit, who have color, who have smell, who have different

things, different kind of fruit you can put. I don't play straight Latin.

In fact, the jazz musicians, they don't want to consider me a jazz musician.

They don't consider me Latin because Latin is "boom, boom, boom,

boom," this kind of thing and I always go against something natural

because my mother was very intelligent woman and we do so many things

together. She inspired me to have fantasy and this I remember. The cinema

is almost violent so I don't like it, so I have this channel 82, who put

all these films 1930-1950.

FJ: Classic channel.

GATO

BARBIERI: Movie classics, yeah, and I tell you I have incredible time.

You pick up movie and all these pornographic and sometimes they put good

movie, but I made music for movie. I have a thousand cassettes of the

best cinema because my ex-wife, who died, she was incredible and learn

a lot of things from her. I have a good background. At this point, I am

happy to play whatever comes to my mind and I have to say, Jaco, in this

sense was incredible. He didn't care about what happened. He come from

the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix, but he did something completely different.

So I like to listen free jazz when they're good. Ornette Coleman have

sense of what he do. Don Cherry, he know what he is doing. Cecil Taylor,

so many other people. I can play some tunes, they are free because at

this point, why can't I do that, play different kinds of music, free jazz,

tangos, but make in different way. All this stuff, I did fifty records.

I made fifty records. I stayed fourteen years without recording because

I go to a big whole. Even I see Charlie Haden. Charlie Haden was with

Ornette Coleman, but now he play tunes with a piano player and him. They

play straight tunes the way everybody knows.

FJ: Standards.

GATO

BARBIERI: Yes, standards, exactly. And I saw at the Blue Note and I can't

say anything because Charlie Haden is a good bass player. He played one

week with a woman, one week with a man. Intellectually, it was very good.

FJ: Then the recordings ceased. For the better part of a decade, you disappeared

from radar all together.

GATO

BARBIERI: I started to record in '96. I stayed from '82 to '96 without

recordings from problems with drugs, from alcohol. My wife, she was sick

and I loved her very much and I don't know what I am supposed to do when

she died. I have triple bypass. The only thing that made my life alive

was contentment to play music. It is strange. My wife, she have with another

man, a daughter and he have a son. His name is Emiliano and in fact, I

put Emiliano for my record, Emiliano Zapata (Chapter 3: Viva Emiliano

Zapata), because after she died, I already, the doctor told me, "You

are close to heart attack." But I was so confused because I know

she will be dying and I never think about it until I play at Blues Alley

in Washington and the pain was so big. I go to the hospital and they do

it. The first month was terrible. The second month was a little better.

The third, we're starting to do something because we're starting with

the French producer, Philippe Saisse, we're starting to make Que Pasa

(Sony). I owe three years of taxes and I had to play fifty thousand dollar

to have the surgery and so many things. What I'm thinking is if I don't

do something, I die, so I starting to think about it and play and play

and play and play, do concerts and continue to make records. This is the

only way I survive because if I stay, I die. Because I am strange, my

life is like, if I am alone, I don't like. If I am with people, I like,

but sometimes I would like to be alone. It is very problematic mind I

have. I had to be. It is the way I am. I was good friends with Marvin

Gaye, Santana. I see one time Coltrane. I never see Miles. I see Miles

play, but I never talk to him. I talked a lot with Ornette and Don Cherry.

For a lot of people, they left because these days to make a record, it

is very difficult. They make a lot of problems. Sometimes I don't like

to make anymore records. I just like to play concerts.

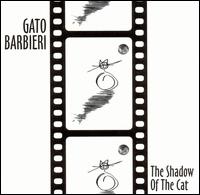

FJ: Did that hold true when you went into the studio to record your new

album, The Shadow of the Cat?

GATO

BARBIERI: Every producer has his own system. You know what I mean? And

you have to learn. The only who don't have system was Che Corazon. I give

the idea and he made some kind of arrangement, but the other ones, they

was computer. They worked sometimes alone. They live two hours from New

York and I can't be everyday there. So he showed me what he do and I say,

"Yes." For me, the best producer was Herb Alpert when I did

Caliente! because all my other records, I produced because I write the

music and we play. After 1976, the music changed. You have to have a producer

and Herb Alpert, he was great because he know as a friend. He know what

I am, what I like. In fact, Caliente!, if you listen, is very beautiful,

very beautiful. It is so natural. I like very much The Third World, the

first record, but there was many like Fenix, El Pampero, Under Fire, Bolivia,

Viva Emiliano Zapata, who was beautiful, a record I made in Buenos Aires.

My memory is not so fast. I am seventy. After I made four record to Impulse!

and after I did four records and the best was Caliente!. Caliente! was

one of my favorite. There I go to big hole, when I stay fourteen years

without recording. I was very thankful like so many musicians, for instance,

Monk, sixty, he don't want to play anymore. He live ten more years and

he died. He was very particular because even when he played he used so

much his mind. He was tired. Sometimes I am tired.

FJ: How are you feeling?

GATO

BARBIERI: My health is very good. I have to say, very good. I don't have

to take any pills for my heart. The only I take pills for is the cholesterol.

I did blood test, but everything was perfect. Maybe my family is very

healthy.

FJ: Do you believe in second chances?

GATO

BARBIERI: No, no, because second chance is like for instance, my son,

he's forty and the son of John Coltrane, he played very good. I don't

know. My son, he like everything so I can't say anything. My mom say one

day, "What do you want to be?" He play very good soccer. "Do

you want to be a soccer player? Do you want to be a musician?" He

said, "I want to be musician." I don't like to push. I was very

happy when I was young. I played soccer and I helped my mom and I was

starting to play clarinet and we moved to Buenos Aires, who is a completely

different city, very beautiful city. So my life is "tango."

The tango is one thing of walking on the life. I think that every music,

even jazz, is the same thing. I like Piazzolla, Astor Piazzolla, but he

died. He was one of the best composers of the Fifties. Unfortunately,

he died in '91, the same year who died Miles, the same year who died my

mom. I live more thinking in my past, when I was young. It is not real.

It is a fantasy. I go to when I was young and this maybe make me young

still.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and give JLo and the Good Will Hunting

guy till the end of the year. Comments? Email

Him