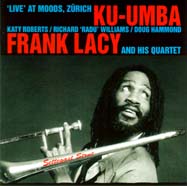

Courtesy of Frank Lacy

Tutu Records

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH KU-UMBA FRANK LACY

I

have developed a fondness for the trombone through the years. Maybe it

comes with age as does wisdom and maturity. Hard as it may be for me to

digest J.J. Johnson or Slide Hampton, I am starting to appreciate the

artistry of bone players like Konrad Bauer, Gunter Christmann, Paul Rutherford,

Albert Mangelsdorff, Ray Anderson, and Frank Lacy. I first saw Lacy live

when he was touring with the Mingus Big Band some ten years ago. He weighed

in by taking a twenty minute (I kid you not because I timed him) solo

that had the audience standing in ovation. His mastery of the instrument

had me wanting to bring him to the Roadshow for some time now, but Lacy

has a hectic schedule to say the least, but he came onboard and shared

his thoughts on his instrument, his music, and his future, as always,

unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

FRANK

LACY: I waited until later to make music as a profession. I started piano

lessons when I was eight, but I didn't make music my profession until

I was about twenty, twenty-one. I started playing the trombone around

the age of seventeen. I was in the twelfth grade. Before that, I played

trumpet and euphonium. The trombone was a very interesting instrument

to me. It is a very unique instrument to me, a very unique instrument

with the positions, slide positions and all. I just the gravitated towards

the weirdness of it, the oddity of how it is being played.

FJ:

What were you listening to?

FRANK

LACY: Wayne Henderson of the Jazz Crusaders. Wayne was from Houston. He's

from the same part of Houston that I'm from. Later on, I got turned onto

J.J. Johnson, Slide Hampton, Curtis Fuller, Albert Mangelsdorff.

FJ:

What type of trombone do you play?

FRANK

LACY: I play the standard, classical trombone, Bach Stradivarius 42G.

FJ: How much

did you pay for it?

FRANK

LACY: Well, I bought it in 1976 for seven hundred dollars, but now, I

would say it costs between twelve and eighteen hundred.

FJ:

How do you approach playing the trombone?

FRANK

LACY: I would say, probably with the approach of a brass player or trumpet

player and probably with the approach of a violin player or string player.

FJ:

How does a trombonist playing a slide instrument mirror a string instrument?

FRANK

LACY: It has positions just like a string instrument.

FJ:

How does the use of a plunger augment the sound of the trombone?

FRANK

LACY: Well, the plunger actually, it makes a stoppage of the air, the

sound when it comes out the bell. But it has enough, the plunger has enough

space in it to give the trombone a different sound when the plunger is

closed. When you open a plunger on the horn, then it has another sound

(imitating doo-woop sounds). That is the main thing. It sounds like something

where you plunge it into a deep abyss or something like that.

FJ:

You had a brief tenure with Art Blakey. What did he impart to you?

FRANK

LACY: Oh, man, confidence. I would say, for the most part, confidence,

a lot of things, but for the most part, confidence. To a certain extent,

it was kind of like going to school, but I think a lot of people that

played with him, they always say the thing about the Art Blakey School

of Music. Well, Art wasn't like that. He didn't really refer to his band

as being a school. A lot of people, as time went on, they called it a

school, but Art didn't look at it that way. Art just looked at it as a

band and that we were here to play some music. He didn't really look at

it as a school. He just had ways that he had the band play and he had

ways that he showed the guys how to act and I guess that you can look

at it being a school in that way, but Art Blakey didn't look at it as

a school himself. It was just a band of cats that he loved.

FJ:

Touch on your close association with Lester Bowie as a member of his Brass

Fantasy.

FRANK

LACY: Well, Lester taught me a lot about the business of music, how to

book my own band without using managers and agents and middlemen. He knew

a lot about the business of music, how to get your band working because

he never recorded on a major record label. He had to do it all himself.

He had to have his own productions. He never recorded on a major record

label all throughout his life. He never got a music contract with Blue

Note or Columbia. But yet a lot of people know about him. That is how

resourceful he was.

FJ:

That is the state of the marketplace.

FRANK

LACY: I think that's the way musicians always have done it. The guys with

the record contracts, they are the few, Fred. Most musicians don't even

get a record contract in their whole lifetime.

FJ:

Is that a first person point of view, considering you yourself have never

had a record contract?

FRANK

LACY: Right, and I don't at the moment. Well, I think America plays a

lot of attention to the saxophone and trumpet and vocalists. They don't

really pay enough attention to trombones, but Europe does. I work pretty

decently in Europe.

FJ:

Is Europe more enlightened when it comes to jazz music?

FRANK

LACY: I hate to say it, but I think so.

FJ:

You recorded a few titles that were released on the little known and even

lesser available Tutu label.

FRANK

LACY: I did three. One of them, I was the musical director for a big group.

I wrote some music for a German musical. But I did two as a leader, yes,

Tonal Weights & Blue Fire and Settegest Strut.

FJ:

Short of knocking on the label's front door, how does one get his or her

hands on these ditties?

FRANK

LACY: I would try Cadence (www.cadencebuilding.com) or KOCH Jazz.

FJ:

During his lifetime, Lester was lambasted by critics for taking on pop

tunes, something you have been doing of late.

FRANK

LACY: Well, Lester came out of the blues. He used to play with Sam &

Dave and Ike and Tina Turner. So he didn't really play in too many jazz

groups. He really came out of the blues groups, Sam & Dave, Righteous

Brothers. He came out of that bag. So that is why I think he had his own

way of turning pop tunes. But that is the problem with these jazz critics,

Fred. They are always trying to say what jazz is and what jazz isn't,

what's good music and what's bad music. Sometimes I think a lot of jazz

musicians and a lot of the general public kind of listen too much to what

critics say. They buy into it.

FJ:

You have held a trombone chair in the Mingus Big Band for some years.

I recall on concert a few years back when the Mingus Big Band actually

played in my hometown of Fullerton. You stood up and took a fifteen minute

solo (I timed him) and it was the first time I had seen an audience hand

a bone player a standing ovation.

FRANK

LACY: For one thing, when you say it was the first time you heard a trombone

player get a standing ovation from the audience. You see that is what

most Americans would say. They don't particularly look at the trombone

as being able to get a standing ovation. Europeans do. Well, it takes

an amount of thinking to play a fifteen minute trombone solo because you

have to be creative. You have to be creative. I'm happy that I was able

to do it, but some people think that's kind of rare to be able to do that.

But, the trombone is such a special instrument that if you really know

what you are doing on it. If you really know the history of the trombone

from Jack Teagarden all the way to Albert Mangelsdorff and J.J. and all

in between, one can put together a somewhat innovative solo because the

instrument lends itself to innovation. For me, I think the trombone is

the closest instrument to the human voice. In Europe, they have country

towns in the hills of Switzerland, in Germany, in Austria where almost

the whole town plays a brass instrument. They have brass bands. The town

has their own brass bands in like Italy, Germany, or Austria. It is a

normal thing. The kids learn how to play the instrument. The instrument

gets handed down to them from their parents and grandparents. You don't

get that here. So they are more knowledgeable about the brass instrument

itself, not only the trombone, but tuba, trumpet, baritone, all the other

instruments. So they are more knowledgeable about the brass instrument.

FJ:

So it is a funding and cultural priority issue. We should place more funding

into our schools, so our youth develops an appreciation for jazz music

and place a greater importance in music and the arts?

FRANK

LACY: Yes, I definitely agree. Place more importance on instrumentalized

music, music with instruments. We tend to pay a lot of homage to vocalists.

Well, they call themselves singers, which I am not really crazy about

the term. I am a vocalist myself. I think singers should call themselves

musicians. Their instrument is the human voice, instead of calling themselves

a singer. When people call themselves a singer, I think about a sewing

machine. They should call themselves musicians, whose instrument is their

own voice.

FJ:

And the future?

FRANK

LACY: Right now, Mapleshade wants to record my big band, but I don't know,

I am trying to get the big band together. We have a big band that plays

every Monday in New York now at the Jazz Gallery. We're trying to do that.

It is hard for trombonists, but we're trying to do that. I'm pretty sure

that I will be recording in the next year or so with Mapleshade, hopefully.

The thing is, Fred, I do more music than just jazz. I don't really want

to sign to a label just on a jazz track. A lot of record companies feel

that it is hard to pigeonhole me because I do so many different musics.

I have like twenty difference ensembles, about eleven that are in the

jazz category. I have nine of them that aren't even in the jazz category.

I do rock, funk, R&B, hip hop. Right now, I am playing with D'Angelo.

FJ:

Did you play on Voodoo?

FRANK

LACY: Yeah, I am on that record. I did the Voodoo tour. I am doing so

many different musics that I am most content when I am doing different

genres of music and not just one.

FJ:

Roy Hargrove is on the D'Angelo record as well. You have been somewhat

of a mentor to the young Hargrove through the years.

FRANK

LACY: Yeah, Roy Hargrove has been on that record as well. We're pretty

close through the years. I'm glad that you realize that I am sort of a

mentor to him. There were a lot of tunes, I played with Roy's Sextet and

a lot tunes that people were associating with Roy, which were my compositions.

Like for instance, on his record that got the Grammy (Habana), the first

tune and the last tune of the record is my tunes, but a lot of people

think it is Roy's. There is a lot of tunes that Roy plays that are mine

that a lot of people incorporate with Roy's music, but it is actually

mine. Roy is always looking at me as a mentor, nice guy. He said he first

met me when he was in the seventh or eighth grade in junior high school

and I was the lead trombonist in the high school big band. We gave a jazz

festival at this college and he came by. His band played and he came and

met me. That was back in 1976 and I can't even remember it.

FJ:

People's perceptions are due in large part because of the stigma that

seems to follow you about being a sideman and further demonstrated by

Downbeat's proclamation that you are "the best sideman in jazz."

FRANK

LACY: The best sideman in jazz. You know, Fred, I don't appreciate it,

but what I am most appreciate about it, it is in part. It is like half

and half. Most sideman don't even get on the cover of Downbeat. You have

to either be a bandleader or some great musician. I had just been a sideman

and made the cover of Downbeat, so I really think that it gave a big kudos

to the sidemen, when most of the articles give the play to the bandleader.

But the bandleader can't do it without the sidemen. But being a sideman

all those years gave me a lot of wisdom. Now, I know how to be a good

bandleader. I know how to be more compassionate to the sidemen because

I've spent most of my time as a sideman. Some bandleaders, they just have

been a bandleader, so they aren't really compassionate enough to the sidemen.

FJ:

It is time people quit referring to you as a sideman.

FRANK

LACY: Thank you, Fred. Thank you.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and enjoys the Stugots. Email

Him.