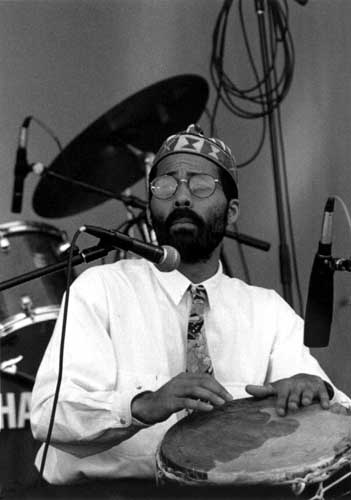

courtesy

of Kahil El'Zabar

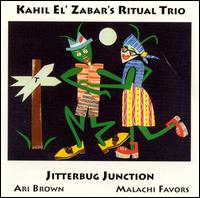

Delmark Records

C.I.M.P.

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH KAHIL EL'ZABAR

Having been given the gift of Archie Shepp (who hasn't been on record

in years) and Pharoah Sanders, Kahil El'Zabar is a Roadshow superhero.

I am honored to bring to you the honorable Kahil El'Zabar, unedited and

in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: It was definitely a passion based on being influenced

by older musicians that I have a lot of respect for, the way they lived

and the music that they played and so as a child, I was able to see folks

like Gene Ammons and the Freeman brothers, George and Von. Roland Kirk

lived here at that time. Yusef Lateef lived in Chicago at that time. Eddie

Harris lived in Chicago, Herbie Hancock, all my older peers in the AACM,

Jarman, Favors, you name it. And to see so many great musicians and the

personas that inspired me, the way of life that I wanted to live. I also

had an uncle, who had played with Bird and Fats Navarro and between him

and my father, they took me to all the cats when I was thirteen, fourteen,

fifteen. I went on the road when I was sixteen and by the time I was seventeen,

I was in Europe hanging with the cats from the Art Ensemble. I was working

with Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre and then I came back and went to college

for a couple of years and then I went to Africa to study. I went back

to Europe around '73 and then from then on, I have pretty much been making

my living as a musician.

FJ: Why percussion? Why not pick up a horn?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: In the Sixties, you had percussionists like Master Henry

Gibson that was playing with Curtis Mayfield and he was pretty much used

as melodic accents. When you listen to a lot of Curtis' work after the

Impressions, rather than a horn player, he's got Henry Gibson out front

on percussions. A lot of people had missed that in the sense of compositional

expression. We had a person in Chicago that taught me and Moye from the

Art Ensemble and Derf Reklaw that worked with Eddie Harris and works with

a lot of folks in the Leimert Park area out in LA. It was an instrument

of pride. It was an instrument of leadership. It was people of African

decent finally recognizing that there was a beauty and a dignity in African

cultural music. I started out playing drums first because my father and

my uncle played drums and so that was always in the house, but with the

hand percussion, there was a certain sense of leadership that was related

to that that I wanted to be part of. So I pursued it and there were a

lot of great teachers and a lot of great examples and at that time, in

the late Sixties and early Seventies, you could actually make a living

doing it. It was kind of interesting, Fred. I came into the music and

there were all kind of working opportunities in jazz and rhythm and blues

or whatever and by the middle Seventies, I was one of the few percussionists

that were out here, especially as a leader.

FJ: What are the conceptual differences between playing hand percussion

and a traditional drum kit?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: Well, with a normal drum kit, and I play that as well,

we're playing with sticks and the coordination is based on having the

left foot do one thing and the right foot another thing, the left hand

one thing and the right hand do a different thing and it has contrary

motion. With the hand percussion, when it comes to African drums and congas

and Latin percussion or whatever, it is using the different parts of the

hand in order to accent and bring out the notes, notes that are in the

higher range of the instrument, the middle range, and then the lower range

of that instrument. It takes a certain physicality that is different than

the trap drums because you are playing with your bare hands, whereas with

the trap drums, you are playing with the sticks. The other challenge for

me was how to create a sound that had the same kind of power in terms

of presence that I had with my trap kit and I think that I've been able

to do that pretty well.

FJ: Why did you journey to Africa?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: I went to the University of Ghana. I was on an exchange

program. I studied with a master ballaphone, which is the predecessor

for the marimba and the xylophone. I was studying music as well as philosophy,

so the way of life for those people and how that translates into language.

While I was there, I realized that my experience in the US was my ethnicity.

I was of blues. I was of jazz. I was of funk. I was of gospel. I had played

all those musics with great people, predominantly out of Chicago and I

wasn't going to try to emulate being of Africa. They would be influences

on my work, but my direct influences are Miles and Threadgill, Gene Ammons

and Curtis Mayfield, Major Lance, Aretha Franklin or whatever. That is

how I came up with the idea of the Ethnic Heritage Ensemble before the

Ritual Trio.

FJ: What made the strongest impression upon you during your time in Africa?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: The honesty, that in terms of people being able to come

closer together, eye contact, hand contact, telepathy that seemed to exist

in everyday of life and how that translated into music because music was

a way of life. It wasn't just something that you get paid to do, but it

had utility in every day of your life. The most important thing was the

real truth in accepting life in its purist sense and then learning to

express that through art.

FJ: Does that stem from their understanding of the fundamentals?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: Well, it is a relationship to the basic ecology. So there

are a lot of complications in nature, right? It changes constantly and

we're not in control of it, so it is actually very sophisticated. But

it is a basis of nature and ecology that define your life rather than

social definitions that have come from our opinions in this urban experience.

FJ: Do the social definitions that we have in this country limit our creativity?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: They are sometimes contrary to nature, whereas in most

traditional cultures, they are in compliment to nature.

FJ: What was the scene like in Chicago when you returned?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: It was starting to go down a little bit. The scene started

drying up between '73 and '75. I think it was the same time as the growth

of the Republican Party.

FJ: How did the growth of the Republican Party contribute to the demise

of improvised music in Chicago?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: Well, the infrastructures of how we are socialized really

started to change from an autonomy kind of control situation. We had come

out of the Sixties where ideas were pretty open and there was a passion

for investigating other ways to live. Then because there were many consequences

with that, trying to fight the Vietnam War, the political struggles of

the Panthers, the Yuppies, or whatever and then a more conservative ethic

coming in with political shifts that were there, media becoming much more

censored, which meant less music of Trane, Trane after '64, not being

on the radio, not hearing Shepp, not hearing Art Ensemble, not even hearing

Lennie Tristano or anything that had to be more thought-provoking in its

programmatic style, the dawning of the marketed jazz musician, that wasn't

necessarily tenured from the street experience of performing, but could

come from the conglomerate, EMI, Columbia, Warner Bros., or whatever.

A lot changed between '75 to about '85 and in the process, some of the

most original voices in the music were subjugated to secondary positions.

But what I also find interesting is that many of the players from the

business, marketing, and the areas of scholarship associated with the

music, those that were there, Cuscuna (Michael Cuscuna), Lundvall (Bruce

Lundvall), Stanley Crouch, as a writer and as a musician, these were all

vanguard people that you see in the Eighties that became part of a more

established environment because they were able to get jobs and there were

certain requirements with those jobs and so the people who inspired their

earlier careers were left out of the mix in the Eighties through the Nineties.

FJ: You mentioned Archie Shepp, whom you featured on the last Ritual Trio

album.

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: Well, I mean the record Bright Moments with Joseph Jarman

and Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre and the new Ritual Trio album that is

one of the newest records with Pharoah because Verve dropped Pharoah.

I find it interesting that David Murray, Henry Threadgill, Archie Shepp,

Sonny Simmons, Sonny Murray, there are so many important musicians, who

are still in their prime, that is what people forget, that these musicians

are between forty-five and fifty years old and so this is a very healthy

time for people. It is a time where they have really developed their ideas

and chronicled them in ways that may not be the so called impassioned

youth that we once were, but we are at an age where we express things

based on a historical analysis that we lived and we can express it honestly

and there is no celebration of our tenure and our commitment of twenty-five,

thirty-five, forty-five years and I think Shepp is just a prime example

of a person who can intellectually articulate the commitment to this music.

He is still an extremely expressive and creative person. Some people talk

about the technique of Shepp at twenty-five, but why would you compare

Shepp at sixty to twenty-five. It is a different scenario. The point with

art is your ability to bring something honest and pure from yourself in

an original way. I think he is still successful at that.

FJ: Let's put the shoe on your foot and tell me what you would do to advance

the presentation of this music if you were president of a major label.

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: I would love to see a label that had the economic and

politic support to be non-genre specific and that the purpose of it would

be to promote the creative commitment and that it would be a decision

that would be more of an A&R kind of analysis. In other words, you would

have some folks who would be aware of someone like Darrell Jones, who

is a bass player, electric bass player, no matter of whether he is playing

Madonna or Sting or Miles or whatever, at his instrument, he is an extraordinary

technician and he has been influential without people really realizing

it in terms of that style of playing. I would love to see him play with

Sonny Simmons, who has the ability to translate his vernacular, his harmonics

in any style of music, but he is not given the opportunity. I would love

to see more projects like the Olu Dara project. I would love to see a

Masters Series like they did at Columbia in the Forties, where they did

that Masters Series with Duke and Louis Armstrong. I would love to see

a thing done where we understand the importance of Threadgill, the composer.

What would you like to do Henry? Would it be a symphonic set or a chamber

situation, a small jazz combo or combination of that? At least document

a project that gives him the full plethora of opportunities of his creative

resource. A great project would be, Joseph Jarman says he is retired from

the Art Ensemble, well, where does that happen? Is there a thing that

Yo-Yo Ma would like to do with Shepp or Pharoah? Why can't we stretch

some of the boundaries and deal with people who have the creative sensibility,

the chops, the dedication, and the love for it? Why can't we find some

young musicians like a Graham Haynes, who are not just focused on bebop

is the only way in which to research as a younger artist the next directions

of the music? It would be a cornucopia more so of celebrating the creative

spirit. Yusef Lateef turns eighty years old and there are no major birthday

parties. He has no major recording contract and he has stayed honest to

his directions, whether we agree with his directions or not, he has been

honest and creative for over sixty years as a performing, improvising

musician, and there is no major celebration of such a testament.

FJ: A shame.

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: It is a travesty.

FJ: What was your vision behind the formation of the Ethnic Heritage Ensemble?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: It was in '73 and it was upon returning from Africa and

a desire to make a statement that was inclusive of my heritage as well

as my contemporary lineage. The Ethnic was developed as a larger group,

originally of about thirteen people, including Don Moye and a couple of

other percussionists and it became a quintet for about two years. We went

to Europe in '76 and we recorded a record in Italy and in Germany and

what happened was that we lost the bass player and other drummer. It ended

up being the three of us and we had developed this book of music that

I had written and we wanted to continue and we decided that since we were

the guys that had hung through everything, that that's what it would become

and it became this two horns and a drum. So it came down to the three

of us and then we had Kalaparusha after that and then Joe Bowie and then

Wilkerson left about three years ago and Ernest Dawkins, who is a former

student of mine and he's been a wonderful replacement for Edward. Recently,

we added Harold Murray on a record called Continuum. We are trying to

keep going.

FJ: And how does that led to the advent of the Ritual Trio?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: The Ritual Trio were actually guys that I had played with

even before Wilkerson and Bowie. They are like my big brothers. I was

on the bandstand with both Ari and Malachi in '68 and '69 and they were

teaching me how to swing and the dynamics and just learning how to play

this music, not in the Ritual Trio, but in various situations, I would

encounter them and they would share with me and in '80, we did the original

recording for Sound Aspects with Lester Bowie and Malachi and it was about

working with my mentors in a pure situation, which I have tried to do

in various sets and give respect to the continuum of generations sharing

in the dialogue of this creative music. When the Ritual Trio comes together,

it is about creating this moment that has a sense of sacrament to the

purity of creating music, coming out of the idea of swing, whereas with

the Ethnic, it is much more in the polyphonic relationship associated

with kind of the transition of African music into the language of Africans

in America. I'm very fortunate, Fred, in that there are musicians, who

are some of the greatest musicians in the world, who happen to be my friends

and have been patient with me with my various projects and ideas and have

helped me make those projects happen.

FJ: Let's touch on your most recent Ritual Trio record with Pharoah Sanders.

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: Well, you have got Malachi Favors, who actually played

the last gig with Coleman Hawkins before he passed. You have got Ari Brown,

who has been in both the McCoy Tyner band and Elvin Jones' bands and Chicago

has always been known for having great rhythm sections, people like Wilbur

Ware and Jack DeJohnette developed his chops as a piano player and a drummer

here in Chicago and Steve McCall and what he did in terms of pulse and

translating that music in the Seventies and Eighties and no one has given

Steve recognition for being a link for what happened from Sunny Murray

on the outside and cats like Billy Higgins on the inside of swing. That

sound that is related to creating a groove and keeping an open space at

the same time, that is what we've worked on with the Ritual Trio for years

and so there is a fraternity in terms of those ideas. Shepp and Pharoah,

they express things in very different ways, but they get to the crux with

a certain honesty of expression that is an important lesson in terms of

these very talented young technical musicians, that if they could lend

themselves to some of the inherent qualities that we have in our hearts

and can bring that out with that technique, that is what both these cats

do so well. I'm really proud of both of those records. They are very different,

but at the same time there is a continuity that is there.

FJ: And let's not forget the heavy record in CIMP with Bluiett.

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: Oh, thank you, Fred. Bluiett is very under-recognized,

but it's the baritone so.

FJ: Let's talk about this venue that you are developing.

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: It is called the Ascension Gallery and Performance Space.

It is my fourth performance space. In the late Seventies, when I came

back from Europe, I opened a space. Then I opened a place called Rituals,

that was a club in downtown Chicago, where everybody played, Blythe, David

Murray, James Newton, my bands, everybody played. I closed that after

three years and then I opened a restaurant that had music and food. This

next space that I am doing is a space working with predominantly young

artists, a lot of indie rock musicians and I am trying to do what Jarman

and Malachi Favors did for me. They created situations in order for me

to develop as a musician. At this point, I can kind of afford the situation

that I'm doing. I learned from younger artists. We are working with spoken

word artists, hip hop artists. We are working with older jazz and creative

improvisers. But the idea is creating a new audience and that new audience

I think is within the internet and the email mailing lists. That technology

has brought about an insular community. I think it can be reversed when

we create and work with that and we can create a community that once again

comes out publicly and fills a certain comradeship with one another and

we can use it without spending as much money in advertising and media

in order to develop this new following that I think exists. If you think

about that college radio is the only true outlet for alternative music

right now. So since we have so many wonderful young people who are diligent

to the task of exposing their communities to what exists, that they may

not find in popular forms of media, then we need to support that and create

environments where they can create. So it is the Ascension Gallery and

Performance Space based on Coltrane's great composition, "Ascension,"

which is what we are doing. We're trying to aspire. We are trying to ascent.

FJ: How far along is the venture?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: Well, we have been here for about six months and we're

building up the space. It is a 5,300 square foot space and it can hold

about a thousand people. Adjacent to it is a 6,000 rooftop in the center

of downtown with the skyline of Chicago. It is the top floor of the building.

We have had a couple of events in the raw with the space. We hope to be

in full motion by the end of August around the time of the Chicago Jazz

Festival.

FJ: How can the general public support the music?

KAHIL EL'ZABAR: I think the most important way to support the music, Fred,

is to actually participate by coming out to live performances and also

supporting the ability to promote that. It is not just about the artists

or the promoter or the gallery space or the club doing it. The public

has to realize that in a sense we are being starved by not taking the

responsibility to demand what we want on the radio, to come out to events

and say these are the kinds of things that we want to share and experience,

and so we need an interactive community that realizes that there is an

unfair void that only through our own responsibility can we fulfill.

Fred

Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and host of his own late night talk

show. Comments? Email

Fred.