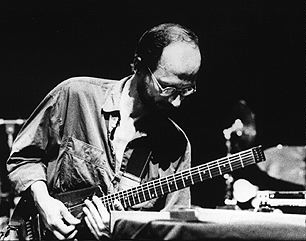

Courtesy of Erhard

Hirt

Photo by Raymond Malentier

happy few records

Nurnitchnur

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH ERHARD HIRT

From

a train, Erhard Hirt, one of the finest free formed improvisers on any

instrument let alone guitar, answered the questions I posed to him. More

and more, like the trombone, I am deepening my appreciation of the guitar.

Although, Wes Montgomery and Joe Pass still seem to bore me (must be a

generational thing), Derek Bailey, Marc Ribot, Bill Frisell, Thurston

Moore, and Hirt peak my interests. But Hirt and Bailey in particular are

too much. I am still trying to absorb Hirt's Trinidad recording and I

received that from Hirt over two months ago. I am honored to present Mr.

Erhard Hirt, unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

ERHARD HIRT: When I started to play music, we where three friends at school

no dancers, no sportsmen, no motor cycleriders but loved rock

music. So we picked up instruments and tried to follow our stars (Cream

and Jimi Hendrix) making terrible noise at the first dance school party.

Getting more practice and under the influence from groups like Soft Machine

and listening to the music of John Coltrane, we developed to become the

local avant-garde jazz-rock group in the '70s. Although improvising was

an important aspect of rock music of that time, first contact with free

jazz came through the activities of Wuppertal free jazz heroes, Peter

Brötzmann and Peter Kowald.

FJ: Was the guitar your first instrument of choice?

ERHARD HIRT: Yes, it was. I picked up the guitar in the Sixties being

influenced by the British blues movement. I was very much inspired from

that horn like long note guitar players like Peter Green and Eric

Clapton but soon found recordings from screaming Otis Rush, elegant B.B.

King and (later) powerful Freddie King.

FJ: It is a daunting task to keep an audience's interest during a solo

concert, is

there increased pressure when you perform alone? If so, why do it?

ERHARD HIRT: There are two aspects about solo concerts. The absence of

musical partners, which you usually interact with first, creates a uninterrupted

connection to the public. Group improvising logically first creates an

communication circle in between the musicians and gives the public the

invitation to join the musical process. To work alone seems to be a bit

more pressure than in a group because all the inspiration could come out

of yourself. But on the other hand, it gives the chance to formulate personal

ideas and concepts, which will be changed and alternated in group settings,

often, very soon. So solo work becomes a kind of mixture between real

improvising and conceptional music. I remember, doing my first solo record

in 1982, I liked the situations: "to finalize own musical ideas."

FJ: How did your work with blues bands help your improvising?

ERHARD HIRT: I love the blues guitar, the very individual style of guitar

players and blues singers (but I hate German blues revival, making most

bands sound like the others). The difference to improvised music is that

you work with a given form and not have to develop that musical form.

But in good blues music, like in many other ethnic music or jazz music,

the form seems to be less important than the expression. The few cords

and the floating harmonic-melodic relations of blues gave a lot of space

for improvising. So it gives the chance and the challenge - even if you

play the same song each night - to make it a new one every time going

beyond the point you played last time.

FJ: You formed a string quintet in the early Eighties, what was the catalyst

for such a venture?

ERHARD HIRT: The string quintet was a totally improvising group. I very

much liked the colour of string sounds and the extended way the members

of the group where using the possibilities of their instruments. Probably

the main idea in that group was to create an alternative sound to the

jazzy sounding sax and drums area of improvised music.

FJ: What was the musical climate like in Europe during the late Seventies

and early Eighties?

ERHARD HIRT: There were a lot of music coops going on, little festivals

and a climate of aufbruch. It was great for me to get in contact to Paul

Lytton and Paul Lovens. I got the chance to work regular with Paul Lytton

who was with his duo with Evan Parker one of my heroes that

time. When I moved to the city of Münster, we founded the Initiative

Improvisierte Musik Münster (I.I.M.) with four drummers and

one guitar player (!) - in 1981 and also arranged concerts and event.

FJ: Was that climate condusive to your brand of improvised music?

ERHARD HIRT: Yes, it was. I think in the Seventies improvised music emancipated

from American free jazz and established its own European style.

FJ: Would your life have been easier if you played bebop instead?

ERHARD HIRT: No, I don¹t think so because I cannot play bebop. I

never had the idea of getting an easy way in making music.

FJ: Is jazz, as history books documented, dead?

ERHARD HIRT: A question for feature pages or jazz critics. I don't think

so much about categories doing music. I still find myself on jazz events,

but I am not sure to be a real jazz player. What I like in the tradition

of jazz are the very strong individual musicians with their own personal

style. The more establishing of jazz - for example to be teached in universities

- has also an aspect to make it to a kind of historic music. But on the

other hand, I see a lot of young musicians who don't think about these

categories. They can get a very good musical training now, playing new

music scores, improvising or learn something about other music cultures.

FJ: Why are European improvisers being looked at for the advancement of

this music more so than their American counterparts now?

ERHARD HIRT: I really believe that in improvised music which was

of course very much influenced from the freedom of American black music

from the Sixties the European musicians found their own styles,

combining the individual personal attitude of jazz with their own tradition

of their European musical history and European new music. If they really

looked serious for their own way in music they there bound to do so.

FJ: In the King Übu Örchestrü, what were the dynamics of

the group and why did you part ways?

ERHARD HIRT: The King Übu Örchestrü was based on a quartet

of Wolfgang Fuchs (reeds), Paul Lytton (percussion, live-electronics),

Hans Schneider (double bass) and myself, which was named Xpact. The orchestra

founded in 1984 included most of the European musicians (from Italy, Swiss,

Great Britain and Germany) I was working with that time. One of the ideas

was being able to listen to everybody in a complex musical structure -

without the concept of having soloists and background roles in the ensemble.

This created a very flexible and sensitive structure, which became typical

for that band. The band combined different characters of players and I

think after some changes in the line up we found a well balanced musical

collective of ten players able to do improvised real time music in live

concert situations. I left that band in '87 because of conceptional differences

with co-organizer Wolfgang Fuchs.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and part of the triple threat

of the Lakers. Email him.