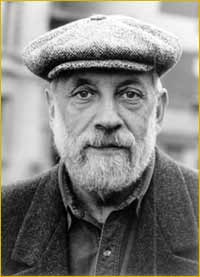

Courtesy of Joel Dorn

A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH JOEL DORN

Man alive, is there a more luckier guy on the face of the earth than Joel

Dorn? He must pinch himself every morning. God knows, I would if my job

was producing Rahsaan Roland Kirk albums. Joel has done just that, as

well as produced a slew of other greats for Atlantic, like the Divine

Miss M herself, Bette Midler and Roberta Flack (whose "Killing Me Softly"

was a tune the love of my life seemed to love to karoake). But his resume

does not end at Atlantic. He is also commander and chief of the 32 Jazz

fleet. And for those of you who have been hiding under a rock for the

past couple of years, 32 Jazz has re-issued, bar none, the best material

period. Major labels can not touch what Joel has been able to do with

essentially what amounts to one Muse catalog. He and his band

of merry 32 elves have released kick ass Woody Shaw, the before mentioned

Rahsaan, and Pat Martino recordings. I went into Tower (I used to do buying

for Tower, but I'm not proud of it) pre-32 Jazz and there was no Woody

Shaw, not even a bid card, perhaps one Pat Martino record, and forget

about it, no Sonny Stitt, and if there was, it was never ordered. So he

is a Godsend I tell you. Who am I kidding? Next time I am in New York,

I'm rubbing him for luck.

FRED JUNG: Let's

start from the beginning.

JOEL

DORN: I kind of got interested in all kinds of music, jazz being one of

them, when I was very young. I'm fifty-seven. During World War II, when

I was a year, a year and a half old, my mother used to play Al Jolson

records every morning and that was the first contact with music that I

had. For that point on, I always had a strong feeling for music. You know

how the randomness of things are, Fred? Like somebody else's parents take

them fishing. Somebody else teaches them how to play chess. I was always

had an awareness of music from a very early age and early on, by the time

I was ten or twelve, I knew I was going to be doing something that had

to do with music. I can't sing. I can't dance. I can't compose. I can't

play an instrument. I can't do anything that involves doing. So when I

was a teenager and I found out that there were people that actually made

records. They didn't call them producers in those days. They called them

A&R men. So I said, "Well, I think that's what I'm going to do." That's

kind of how I go into it. The add-on to that story is I was like one of

those guys that listened to music twenty-four hours a day. It was music

and sports. That was kind of it. I heard a Ray Charles record one time

when I was in my grandmother's kitchen. I think it was 1956, on a cold

winter's night. And I was so knocked out by Ray Charles, I wrote his record

company and it started a five-year correspondence with Nesuhi Ertegun,

who is one of the principals at Atlantic. In 1961, when I was nineteen,

I became a disc jockey on a jazz station. That was kind of the beginning

of my producing career. Nesuhi was my mentor and I was apprentice to him.

So I made a few records on my own, a few records for him and then I joined

Atlantic full time in 1967 when I was twenty-five and stayed there for

the better part of seven or eight years and did the bulk of the work that

I've done with Atlantic.

FJ:

Let's touch on that work you did with Atlantic, you produced monumental

recordings from Rahsaan Roland Kirk (Bright Moments, Blacknuss,

Volunteered Slavery), Les McCann (Swiss Movement), and Roberta

Flack (Killing Me Softly).

JOEL

DORN: Well, it was an interesting time. First of all, I told you, Fred,

I became a fan of Atlantic Records as a consequence of falling in love

with Ray Charles in the mid-'50s. So I loved Ray Charles. I loved LaVern

Baker, The Modern Jazz Quartet, The Drifters, The Coasters, John Coltrane,

Hank Crawford, "Fathead" (David Newman), that whole Atlantic family. It

was the most amazing collection of artists across the board that I had

ever come across. There never was a company like that. So I made my mind

up early on, like in tenth grade, that I wanted to work at Atlantic Records

and I wanted to be one of the guys that made or helped make their records.

I'm a big sports fan, Fred, and I use sports analogizes a lot. If I were

a baseball player, I would have wanted to have played for the '55 Dodgers.

Being as someone who has made his living in music and whose life pretty

much revolves around music, I can thing of no better place to be than

Atlantic. The three principals, Ahmet Ertegun, Nesuhi Ertegun, and Jerry

Wexler (Vice President), were all real music men, but they were all intellectuals

as well as having a great sense of the street. So there was never another

combination of guys like that. To be able to work at Atlantic, it took

you a jillion years to get in there. It was a closed shop. But once you

got in, they just turned you loose. They gave you enough rope to hang

yourself or to climb up a cliff. It was really like playing for the '55

Dodgers. It was a soulful place, but they were also the best. You lived

or died by your own taste, so if I wanted to sign Rahsaan Roland Kirk,

I could sign him, but I could also make records with Jimmy Scott and when

I got hits with Roberta Flack and Bette Midler, it enabled me to bring

in the Oscar Brown, Jr.s and the Ray Bryants and other people that I liked.

As long as you made your hits, you could do what you wanted. You never

knew where it led. For instance, we signed Roberta because we signed Les

McCann. He's the one who found her. Roberta was one of the two people

along with King Curtis who found Donny Hathaway. Without getting maudlin,

as much of a family feel as you would ever want to have in a business,

we had at Atlantic. It was a great place. It was so good, it grew. And

in the mid-'70s, I left because it wasn't the same place. It went on to

become one of the most successful record companies in the history of music,

but that old Atlantic, that was the place that I liked. For a guy like

me, I mean, I grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania, outside of Philadelphia.

It was like growing up in something between a Sinclair Lewis novel and

a Norman Rockwell painting. To be able to a world citizen and a man of

such exquisite taste and vision as Nesuhi is the great stroke of luck

in my life. It was really something, Fred. You walked down the hall and

Dr. John would be here and Aretha Franklin and Eric Clapton would be there.

It was just this smorgasbord of geniuses that all happened to land at

the same place at the same time.

FJ:

Les McCann credits you with the majority of his success.

JOEL

DORN: Well, that was the point if I can interrupt you. Any success I've

had, has always been, like I said before, this isn't false humility on

my part or some kind of way of saying, "Oh, golly I can't do nothin'."

I can't do anything. But I know talent and I know, I think, how to put

it into a studio and let it express itself and then either complement

it or frame it or do something. I had listened to Les's records from before

my disc jockey days and I had seen him in the clubs in Philly dozens of

times while I was on the air and I knew that Les McCann could reach people.

Was he the greatest jazz musician that ever lived? No, but he didn't pretend

to be or really give a shit about it. He knew how to touch people and

he knew how to reach them in a club. He could swing his ass off, play

pretty. He was a great entertainer, terrific singer. You didn't know it

from the records that he made. So one of the first things we did when

I came to Atlantic, Nesuhi said, "We've been offered Les McCann, what

do you think?" And Les had pretty much had this reputation as a gospel

tinged, commercial jazz pianist, blah, blah, blah, and who cares, but

I knew him from the clubs. We signed him and the first thing I did was

I put him in there and I knew, we had kind of become pals when I was a

disc jockey, I knew what he wanted to do. I knew he didn't want to have

someone yelling, "Cut one. Cut two. Fix this." He just wanted to go into

the studio, played what he played, and see what happens. I had seen him

in the clubs and especially watched the way chicks related to his singing.

Women went nuts when he sang those pretty ballads. That's how we got "With

These Hands." And then when he laid down all his stuff, I brought Bill

Fischer in to overdub strings on some things because he wanted to do something

on a larger format, but not something that sounded something like a fucking

Clairol commercial. Les really flourished at Atlantic. If you're the producer,

you don't have to tell everybody what to do and how to do it. I did this

and this is my drum sound. I just went after talent. I didn't have to

tell Rahsaan and Yusef or any of those people what to do.

FJ:

As a producer then, what was more important to you, critical acclaim or

public appeal?

JOEL

DORN: I'm going to be honest with you, Fred, because I'm fifty-seven now

and I'm too old to lie anymore. When I was a kid, I started when I was

in my early twenties, I wanted to make great records that sold and have

everybody point to me and say, "Wow, this guy is a phenomenal producer."

So I was ego driven in the early days. As it went on, I found out the

curse of pride and vanity, so not too far into the game, but farther than

it should have been, I became focused on finding great talent and capturing

it properly. And when I did throw my two cents worth in, to make sure

it was right and it fitted or complemented or augmented what the artist

did. It's a long process to get to that, especially when you started off

as driven as I was and as young as I was. When you talk about critical

acclaim or record sales and things like that, you really want all of them

and then you do a lot of work and you see where it lands. I found that

certain artists I worked with who should have been acclaimed critically

like Rahsaan weren't. What we did was we recorded him as much as we could,

so that we could build up the body of work, same with Yusef, same with

Les, Eddie, "Fathead," Hank, a lot of those guys, but especially Rahsaan

and Yusef, because people tended to dismiss them as oddities or miscellaneous

category winners or in Rahsaan's case, a clown or a gimmick, someone who

is clownish or gimmicky or vaudevillian or an oddity of some sorts. Proved

them wrong on that one. We bet your ass we did.

FJ:

Funny how he has become a critical darling and he's been dead for over

twenty years.

JOEL

DORN: Now, they can't praise him enough. But you know what, Fred? You

really can't get mad at people because of their limitations, so as pissed

off as I was for years. It was nuts, it was half of what killed Rahsaan.

It made him so nuts because he never got the recognition he wanted, which

was his fault not theirs. Eventually, things kick in when it is time for

them to kick in. I'm just glad we were able to keep fanning the flames,

so by the time people did catch up with him, we were ready. The records

were there and we had set up a mechanism where by people could read about

him and listen to him and understand what it was, what he did, what he

was, what he wasn't, and what he was about.

FJ:

Your legacy is there in the Rahsaan records alone, what in the world prompted

you to take on the headache and form your record company, 32 Records?

JOEL

DORN: Real simple, Fred, one sentence. Everything that I wanted to do,

there was no record company that either would let me do it or was even

interested in it. So I figured out that if I want to do what I want to

do, I've got to do it on my own.

FJ:

With your purchase of the Muse catalog, you were able to release a horde

of vibrant material that was criminally deleted or neglected.

JOEL

DORN: That was the plan, but that was the plan I couldn't sell. I approached

every catalog in the world with my plan. I approached everybody for three

years. They just looked at me like I was a junkie or communist or transvestite,

something they didn't want in the building.

FJ:

Is it amusing to watch record companies ripping that philosophy from you

now?

JOEL

DORN: Well, it's great that the material is getting out again. I mean

on all the labels. If we had anything to do with people looking more deeply

into their catalogs and get it out, great. But like, I think it was Jimmie

Lunceford who said, "It ain't what you do, it's how you do it." You've

really got to treat these things with respect. You've got to make them

easy for people to get to. You want to put out Kind of Blue for

$17.98 or $18.98. You want to put out Giant Steps for $17.98 or

$18.98, that's cool. But you can't put out every record that was ever

made at $17.98. It just isn't fair. It's not fair to the listener, as

much as it's not fair to the artist, as much as it's not fair, ultimately

to the record company because you've got to make it so the stuff is accessible.

You have to make it friendly for retailers to sell it before you can get

it to people to buy. Our theory was, "Give them the best music you can

at the most reasonable price, in the most appealing attractive package."

And it worked.

FJ:

You created quite a stir with the packaging for the Jazz For series,

who knew that a sexy woman on the cover equals sales?

JOEL

DORN: You used the word sexy, Fred. I'm going to tell you the word I use.

I'm going to use the word sensual. Those records were made to appeal to

women, not to men. If I wanted to appeal to men, I would have gone to

Penthouse or Playboy. I would have gotten the hottest chicks I could find

with the fullest lips and the dirtiest eyes and I would have put them

on the cover. We went to Elle Magazine because we wanted to use

fashion photography. Ultimately, you have a shot to appeal to men and

women, but women first with fashion photography. And the music has to

fulfill the promise of the title and the whole package has to work. That

was a marketing thing. It was something that I wanted to do for a long

time. Look, Fred, much of it was by luck. We went to Elle Magazine

and we made the record. It was originally called Music for a Rainy

Afternoon, the first in the series. It was designed for something

called the Elle woman. They gave us free advertising pages in return

for us doing the manufacturing and putting the package together. It was

a bomb in the magazine. We got four free months, which would have cost

us a couple of a hundred thousand dollars if we paid for it and we maybe

sold a thousand CDs. Music for a Rainy Afternoon designed for the

Elle woman. When we went to retail with it, the only way that I

would agree to go to retail with that package was if we took the Elle

logo off the cover, because it doesn't mean anything in retail and if

we changed it from Music for a Rainy Afternoon, which was supposed

to not scare away the Elle woman, whoever that is, and we changed

it to Jazz for a Rainy Afternoon. The whole thing happened by mistake

anyway. I wish I could tell you, Fred, that it was my brilliant idea and

I knew it from the start, but I didn't. What happened was, we put it out

and there's a girl named Anne Topka, who works for our distributor (Rykodisc)

in the Pacific Northwest and she loved the record. So she went to a retailer,

who was one of the retailers that she called on as a representative for

the distributor. After we put it into one of the listening posts because

she thought people might like it and they sold twenty-five records the

first day in the listening post. People were drawn to it by the cover

and then the music actually worked. From there, the one smart thing that

we did was we saw that if you could sell twenty-five in one day in Portland,

Oregon, well, then this could pretty well translate into every other market

in the country. So we picked it up and ran with it. When I say we, that's

not the show business we, that's me and the guys here. I've got a great

publicity and promotions director. I've got a great label manager, great

sales people, and a great sales manager. So we really chased that one.

FJ:

Give me the sales numbers on it so far.

JOEL

DORN: We're a little under a million for the series. There are six albums

in the series. The first one is approaching a quarter of a million.

FJ:

For the benefit of those who are not in the loop, what do those sales

number mean in laymen's terms?

JOEL

DORN: That would be the same as if Madonna sold ninety million records.

That's what it would be like or if the Backstreet Boys sold two hundred

and eleven jillion records. It's unbelievable. And it's part of my theory

that if you just follow your heart or chase your instincts, I mean, listen,

Fred, the hit records that I've had if you go back to when I was in the

studio with Midler or Flack or Les McCann or Eddie Harris or the Neville

Brothers, any of those people, all the records that I've made, I've made

close to two hundred albums in the studio and another two hundred compilations,

reissues, box sets, stuff like that, there is only two times when I was

in the studio that I knew that I had a hit record. One was "Killing Me

Softly" (Killing Me Softly) by Flack and the other was "Do You Want to

Dance?" (The Divine Miss M) by Bette Midler. All the rest of the time,

I was just doing shit I dug or stuff I believed in or just chasing a thought.

It kind of happened by itself. I signed Roberta before I even heard her

because Les insisted we sign her and Atlantic was the kind of place that

listened to its artists in those days. So we signed her and that record

was out for a year and a half before Clint Eastwood called the office

one morning and told me that he wanted to put "The First Time Ever I Saw

Your Face" in a movie. His first movie that he directed called Play

Misty for Me. All of the sudden, it's in the movies four million records

later. I signed Bette Midler against everybody's desire at Atlantic and

everybody insisted that she was a visual act, not a record act. And I

knew I had it with "Do You Want to Dance?" and to a certain degree, "Boogie

Woogie Bugle Boy." Any hits that I ever had happened almost by random

or by chance.

FJ:

You put a lot on the line with Jazz For series, you know what they

say in the record business about compilations.

JOEL

DORN: I know what they say about everything. You know what, Fred? Who

the fuck knows? You know what I mean? I remember when we did "The First

Time Ever I Saw Your Face" by Roberta, I had been getting calls from jazz

disc jockeys all over the country saying, "Put this out. Every time we

play it, the phones light up at the radio station." So I went to the powers

that be and I said, "I want to put out this thing by Roberta Flack because

all the jazz disc jockeys are telling me that every time they play it."

In those days, a jazz record could cross into R&B and then into pop. There

was a root that you could take if you wanted to bust a jazz record like

"The Girl From Ipanema" (Getz/Gilberto) by Getz or "Poincianna" (Ahmad

Jamal at the Pershing) by Ahmad Jamal, those kind of hits. They kept telling

me, "Nah, it's a ballad. It's too slow. It's too long. It's too tall.

It's too short." But when it got into the movie, the disc jockeys were

proven. The older I get, the more I realize that a lot of it has to do

with luck and a lot of it has to do with following your instincts, following

your impulse. Lucky I was in an environment at Atlantic where I was allowed

to do that. That environment changed and Atlantic became like the rest

of the companies. I left because I knew first of all, that I would get

thrown out of there shortly anyway and I didn't want to stop doing what

I was doing. So I did it for another six or seven years and then I took

some time off, because first of all, I was burned out and secondly, I

knew I had to reinvent myself because the time that I flourished in was

over and so were the kind of artists that I liked to work with. So I took

off in the early '80s and I ran out of money so I came up with the new

concepts of a more documentary approach, the box sets and the unreleased

live stuff and the compilations, reissues, and shit like that and it's

worked. I'm really lucky and I got a second career.

FJ:

Your son Adam has been putting some of the material together.

JOEL

DORN: Adam's got it!

FJ:

You have been doing this for nearly forty years.

JOEL

DORN: I'm coming up on forty years in 2000.

FJ:

And you are approaching your fourth year of reissuing the Muse catalog,

are you running thin on material now?

JOEL

DORN: It is starting to get thin.

FJ:

Then what is the outlook for the next handful of years?

JOEL

DORN: All plans that I have are always kept secret. I'm like a scientist

who has a lab, deep in the mountains someplace. I grew up with comic books

and I maintain that comic book attitude. Take a deep breath and have a

nice winter (laughing).

FJ:

Speaking of comic books, who is the hell is "The Masked Announcer" and

how is he getting so much work?

JOEL

DORN: Here's where "The Masked Announcer" came from. When I was a kid,

there was a disc jockey in Philly and when UHF television first came in,

it was the first time we had more television stations. So instead of just

going up to channel twelve or fourteen, you had forty-eight, twenty-nine,

fifty-seven, so they hired all the disc jockeys in each city to do their

local commercials at, I guess, fifty or a hundred dollars a pop. I came

up with this character, "The Masked Announcer" and I wore a mask and a

cheap suit and it was kind of a tribute to Sgt. Bilko and I sold all this

slop, clear plastic slip covers, cheap carpeting, vacuum cleaners, storm

windows, vegetable choppers, and I created this character and I had a

lot of fun with it for a couple of years, but then I was too busy with

Atlantic and I was on the road all the time. So when I formed my own production

company, everybody always says, "Produced by Joel Dorn for Joel Dorn Productions."

I was like, "Enough already." So they said, "What are you going to call

your production company?" I said, "I want to call it The Masked Announcer."

And so it was just what I thought was a clever name, but it stuck. I get

asked that question once a week.

FJ:

What's with the sign off "Just Keep A Light In The Window?"

JOEL

DORN: My parents went to New York for the weekend in 1947. I was five

or six years old. I used to listen to the Hit Parade. My grandmother would

let me stay up. The Hit Parade would come on the radio from 10:30-11:00

on Saturday night and they would do the top ten songs of that week. Of

course, I used to sit there trembling to find out what the Lucky Strikes

number one song in the country was. The announcer would go, "And now,

Lucky Strikes presents the number one song in the country as determined

by Billboard Magazine." One of the singers on the Hit Parade in

those years was Frank Sinatra, so at the end of the show, after they did

the number one, which ever singer sang the number one, Frank Sinatra would

say, "Well, that's it for the Hit Parade for this week. Remember smoke

Luckys and keep a light in the window." (Laughing) I thought that was

so hip. Wow, stay the fuck away. I was like a little kid, but I thought

that was such a hip way to say goodbye. When I came back to career number

two, I always was touched by that. It was always a very warm thing. I

think that when I was doing Rhino box sets, when I was over at Rhino for

a while, I made that my sign off and people seemed to like it. I got the

most touching email today from a guy and it was about Rahsaan and how

happy he was that we were putting the Rahsaan stuff out, but it was more

than that. It was a beautifully written thing and at the end of that he

said, "Thanks so much. The light is on and getting brighter all the time."

We get five of those a week. I'm glad you asked those two questions, Fred.

FJ:

I have been lobbying for a Rahsaan and Woody Shaw box set. When is it

coming?

JOEL

DORN: We're going to do a Rahsaan box set next year, unlike any box set

you have ever seen or heard in your life. It's totally Rahsaanic. Woody

Shaw, no plans right now, but you know, Fred, we've really been pumping

Woody.

FJ:

I have to commend you, a couple of years ago, you looked at the local

Tower Records bin and under Woody Shaw, there was maybe one record. And

now, it is full with 32 material. You have started a Woody resurgence.

JOEL

DORN: You don't have to be a genius to do that. Woody Shaw, just because

you're great doesn't mean the world knows it. Just because you're great

doesn't mean you're going to get recognition in your lifetime. I had a

call from Horace Silver. I was on the radio. He said, "I've got a new

group here." He had broken up the group with Blue (Mitchell) and Junior

(Cook) and he said, "I've got a new group and I'm bringing them into Philly.

I want you to check them out." I was a big fan of the Blue and Junior

group. I thought that was one of the best groups of that time. I was a

little taken aback. Why break it up? They were incredible, but he wanted

fresh meat. So he said, "I've got Joe Henderson and Woody Shaw." I hadn't

heard of either of them, although I had heard of Joe Henderson. I think

I heard of him play on a Herbie Hancock record on Blue Note. I didn't

really know his work and Woody Shaw, I had no idea who he was. When I

saw Woody and Joe together, that was some combination. I knew from the

first note that these two guys were going to be big players. And they

were. Woody was a tortured kind of guy, a star-crossed kind of guy. He

did a lot of good work, but he never really made it. Musicians knew about

him, so when we bought Muse, one of the reasons I bought Muse was because

of such an unexploited catalog and I knew there was lots hidden in there,

Woody, Pat Martino, Groove Holmes, all these guys. And I knew there was

millions of dollars in records worth of sales hidden in that music. It

was handled in a way that led me to believe you could really do something

with that.

FJ:

Taking a page from Frank Sinatra and Joel, "Keep A Light In The Window."

All my best.

Fred

Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and Interview Specialist. Comments?

Email

Fred.