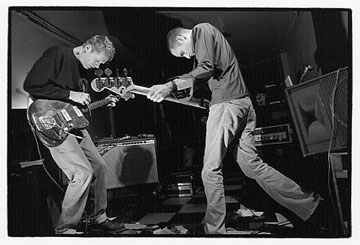

FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH NELS CLINE

Nels

Cline is a local hero round these parts. But it wasn't until I was in

Boston at the tail end of the summer of '99 that I was impressed, really

impressed. I was in a used record store and a remake of Instellar Space

caught my eye. I bought it on a whim and listened to it on the grueling

plane ride back on TWA, which must stand for The Worst Airline, with a

stop off in St. Louis (you can address sympathy emails to

fred@jazzweekly.com). I must have listened to the CD cover to cover

at least half a dozen times. I was hooked. It was the most adventurous

guitar record I had heard in years. The Wadada Leo Smith Yo Miles! record,

which Cline was on is close. Buy it now. If you don't have the money,

give up the pink slip to your car. What is a sports utility worth these

days anyway. Gas prices are through the roof. You'll thank me later. So

here he is, the man with balls of steel to have made this record, unedited

and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

NELS CLINE: I started playing guitar in earnest, probably around 1967,

the height of creativity in popular music. I was initially into surf music

as a little kid. By 1967, things had gotten truly psychedelic and obviously

Jimi Hendrix was a huge inspiration. My twin brother Alex and I were versed

heavily in the rock and roll scene of the late '60s and early '70s. Then

in 1971, a friend of ours loaned us a copy of John Coltrane's His Greatest

Years, Vol. 1, which he had bought for his poet dad's birthday and he

thought that Alex would like it because he was so into Frank Zappa. So

we put on the record and quite simply, ever since then, our paths changed.

That began our desire to learn more about this kind of music. We felt

we had missed some huge movement in music. I think my idea of jazz prior

to that was my dad's big band records and Ella Fitzgerald records with

Nelson Riddle and maybe some cartoonish idea of what bebop sounded like,

something fast and wild. Coltrane's sound and Eric Dolphy's orchestration,

the whole thing was so immediately appealing, but at the same time, so

dark and mysterious that we had to know more about everyone that ever

got near John Coltrane, which of course led us to not just Eric Dolphy,

but to Miles, and from there you can pretty much get the whole thing.

So that is what happened. That was around 1971. We were about fifteen.

FJ: What stood out about Trane?

NELS CLINE: Well, certainly it's his tone. There is something so commanding

about it. It was truly like nothing I had never heard before. There is

something about his tone, which I ended up reading, was in his earlier

days very controversial. He was considered very nasal and very dry. People

thought he was very dry, that he just practiced when he soloed. Whatever

that tone is, for me, it had an immediate appeal and it was very vocal,

but there is a certain kind of reserve in Coltrane's style that makes

it somehow at times, maybe all the time, seem even more emotional.

FJ: Trane has an uncanny ability to appeal to the youth.

NELS CLINE: It is fascinating to me to have read later all the anti-jazz

controversy, because certainly jazz as a tradition is not my tradition.

I'm just this white kid that grew up in West Los Angeles and I was rock

and roll obsessed. Popular music at that time for so many different artists

was about how far out you could go, how much you could do to blow people's

minds. That is why mind-bending songs were in the pop mainstream. So to

hear these guys playing instrumental music, which for us was kind of the

main thrust. We were never lyric bent. I'm sorry, Fred, that everything

I say was we, but everything I did growing up was with my twin brother.

We played music together. We listened to music together everyday. Our

paths are inextricably linked. That is sort of the thing about being a

twin in some ways, I guess. To hear these people playing acoustic music

that had so much color and timbre and mood, it was immediately appealing.

Certainly, I don't think that we had ever been drawn or repelled by the

saxophone, but it was never a main thing with us. He just made us sit

up. Later, hearing Eric Dolphy had that same effect, especially on my

brother. Interestingly, my brother also immediately got into Ornette and

the Art Ensemble of Chicago. He pretty much hit the outskirts right away.

It took me a long time to warm up to Ornette. I was really one of those

Coltrane acolytes for years. Certainly, later, Ornette became one of the

key figures in my musical life. I was also a philosophy student around

this time. I was not a music major in school. I was a philosophy major.

FJ: What college were you attending?

NELS CLINE: Occidental College.

FJ: In Glendale.

NELS CLINE: In Eagle Rock, actually, where I now live. I didn't get a

degree or anything. I left after a year. I was really interested in the

metaphysical and Western philosophy and I think Coltrane, the more I learned

about him, the more he was my guy. You have to remember around this time

was Mahavishnu Orchestra and all that kind of Indian mysticism that was

infusing the jazz scene. That appealed to me greatly.

FJ: It is telling that Alex was engrossed in Dolphy.

NELS CLINE: Well, my brother bought as many Dolphy records as he could

find. I heard a lot of Dolphy because he used to listen to a lot of Dolphy

and I think that the record that we were most taken by was Iron Man, which

has a very atmospheric kind of ambience to it in the way it was recorded.

My brother was relating it to pieces that he liked in Frank Zappa. It

is funny on how much I learned about the music since then, how we were

sort of undaunted that there were no guitars and although it made it difficult

to figure out what I was going to do with the instrument.

FJ: That is a tough gig to have Trane as your primary influence and you

are a guitar player.

NELS CLINE: Yeah (laughing). It's funny, Fred, that even as I was someone

enamored by Jimi Hendrix, I never tried to play like Jimi Hendrix. I used

music as a point of departure and not as something to imitate eventually.

I thought that Jimi Hendrix's sound was pretty much untouchable and couldn't

be imitated, so I never tried to sound like him and then people came out

sounding like him, it was not only shocking but very offensive to me.

A lot of times, great voices in music spawn generations of imitators that

almost destroy the music. I don't know why I never chose the path of imitation,

but I think it was because I felt incapable of playing well (laughing).

So I thought what I would do is the integrity of the composition rather

than my own technical mastery or listen, I can play John Coltrane's lines

on the guitar. I'm not bagging on that because it is amazing, but I never

tried to do that. But it was confusing what sound to use on the guitar

anymore. I stopped using effects completely for years. I became so frustrated

that I played only acoustic for years. It is what John Abercrombie called

option anxiety, talking about how many choices there are for an electric

guitarist, just in terms of the sound, as opposed to blowing into a saxophone.

There are ways to get different kinds of tone, but they are all basically

shades of the same sound. A guitar can sound like anything at this point.

Whether you play with a pick or your fingers or whether you play with

light gage or heavy gage can have a huge impact, let alone all the effects

that you have available now.

FJ: As twins, simply by virtue of appearance, you and Alex have a unique

bond.

NELS CLINE: We were pretty much inseparable growing up. We did everything

together. This is certainly not true of every twin. I have heard of twins

who feud their whole lives. Certainly, I have nothing to compare my life

to, because I don't know what it is like to not be a twin. We endeavored

to differentiate our personalities by dressing differently. People without

thinking decide that you are really half of a person. They say things

to you like, "Where is your other half?" I think that perhaps there is

a strong desire to assert one's identity. We were pretty much seamlessly

harmonious in our pursuit. It made it easy to form bands because we usually

had two-thirds or two-fourths of a band automatically and had the same

aesthetic goals for the most part. Over time, our twin communication became

so attune that I had to make a conscious decision to not play with Alex.

It was getting too scary. We would play the same rhythmic figures and

the same accents. It was starting to get almost annoying (laughing). Technically,

we are what are called mirror twins, a type of identical twin. Someone

recently told me at this concert of John Carter's music, this woman told

me that mirror twins apparently split apart at the very last second. What

we are is essentially kind of opposites, not just personality-wise. I'm

left handed and he's right handed. When we were kids, if you walked up

behind me if I was looking at myself in the mirror, you would think I

was Alex. In other words, I look like Alex when I am looking in the mirror.

Interesting also, you know, Chuck Manning, he's a mirror twin. What are

the chances of that? His brother is a trumpet player.

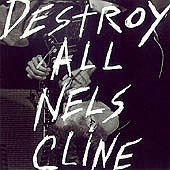

FJ: It was ballsy of you to remake Interstellar Space. You are really

putting it out there in the wind.

NELS CLINE: I know. I will preface this. As a teenager and even playing

music in my twenties, I was a completely nervous, self-effacing to a fault

kind of person. If I thought about it, I would have never done something

like this. There is no way. I would have been too scared. I never had

any compunction about releasing material because I was always confident

in the intent of what was trying to be accomplished. There were a lot

of musicians that I played with that I later found out resented me for

releasing records because I am not as good as John Coltrane. They never

did anything very creative even though they are incredible musicians.

I have never worried about it because I have always thought of myself

as being who I am. That said, I was never the kind of guy that learned

a million songs and could play like so and so. The idea seemed impossible.

As the years have progressed and I have gotten a lot more playing under

my belt and played in a lot of different kinds of contexts, I have relaxed

a lot about myself and about my playing. As ridiculous as the idea of

covering Interstellar Space seemed, I just didn't take it so seriously

that I felt it couldn't be done. I wanted it to be an homage. It did start

out as just a joke, which was to say that I was playing with Gregg and

he was playing his vibraphone with amazing speed and I had never played

with him on drums. I just joked that we might as well play Interstellar

Space. I think something about that statement stuck in Gregg's mind. He

saw that there might be a reason to do that, that it was an interesting

idea. The reason we decided to do it was not just to say how much we admired

this music, but also to submit our alliance with Coltrane's later music,

which in certain camps is maligned. People look at Coltrane's later music

as some kind of desperate search that went nowhere. Certainly in some

camps, free jazz in general is given the short stick, as I see people

like Ayler and all the people that we were listening to on the New York

scene. That music seems to have not gotten its due from the historians.

This music wasn't really taken all that seriously. I think that Gregg

and I decided that we would make a statement. That music has been extremely

important to us. It pretty much has affected the way we play and think.

That is why we decided to do it and risk being ridiculed. It was an excuse

to have a really, really intense time playing music together and challenge

ourselves. I think I thought about all the elements later, but it was

too late then.

FJ: The album on the Atavistic label (www.atavistic.com)

was released more than half a year ago. I was in Boston in October and

went into a used record store about a block and a half from the Berklee

School of Music and was rummaging through the used jazz CDs and ran into

a copy of your release. I bought it as something to listen to on my plane

ride home. I must have listened to that thing half a dozen times from

Logan to LAX. I have been driving the bandwagon for this thing and finally

it is getting some pub.

NELS CLINE: Yeah, I never have any concept of how the records are doing,

but I think that for one thing, it helps that it is not my music (laughing).

Also, Atavistic is well distributed so I think it is doing well. It is

funny. I never think about such things when I release records. Most of

them are on such tiny labels. There is so much out there and what I am

doing is so unobvious that it takes a little time.

FJ: Michael Dorf has broken ground for a Knitting Factory here in Los

Angeles, what impact do you see and has he spoken to you about your possible

role there?

NELS CLINE: I just can't handle the idea of booking anymore. I can't handle

the idea of people calling for gigs everyday. It had its moment for me.

Without getting too far into this, the idea of working for the Knitting

Factory is a little too iffy for me. It puts me in a position that I just

don't want to be in. Just as a booker, every time you go out and listen

to something, someone hits you up for a gig. I did meet with people from

the Knit and I am going to call Dorf this week. I am perfectly willing

to consult with them. I think they have a really healthy curiosity about

the scene here and I think they are pretty knowledgeable about it at this

point. I want to make sure that the locals are considered and that we

are not just tokens.

FJ: You told me in a conversation we had before that you don't like to

play in over 21 clubs, why?

NELS CLINE: I did a lot of touring in rock clubs and rock venues all over

America and I built up a following of a younger audience, which I feel

that college kids because they are the ones coming to the shows, not only

deserve to be exposed to everything, but that audience has the most open

mind. I think this is true from my own experience and if I have a choice

to play a show, I want to be able to play to everybody that wants to hear

the music. The main thrust of a gig sometimes is selling drinks. I am

committed to it philosophically and there are people underage who want

to hear me play and if they cannot get in, I am shooting myself in the

foot. The youth is not just our future, to me they are the most open-minded

and the most curious because they have not become jaded and stale yet.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and Interview mogul. Comments? Email

Fred.