A

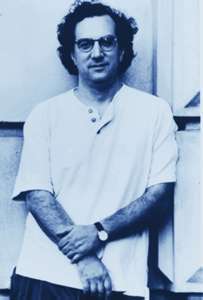

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH URI CAINE

Downtown isn't just a zip code and Uri Caine isn't just a piano player.

Caine is a brilliant improviser that combines his subtle, but evident

knowledge of classical music with his tremendous improvisational creativity.

His work with Mahler is the stuff that makes legends. I consider it an

honor to speak with any musician, but I particularly enjoyed my time with

Caine, whom is quickly becoming a favorite of mine. It is Caine, unedited

and in his own words, enjoy.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

URI

CAINE: I grew up in Philadelphia and there was a pretty lively jazz scene

going on there with people like Philly Joe and Mickey Roker and Hank Mobley,

so you could actually sit in and play with those guys. That's what I was

always aspiring to as I was growing up there. I was studying with this

French pianist named Bernard Peiffer, who was a really big influence on

me. At the same time, I was getting into studying classical music, taking

piano lessons, and studying composition. I went to the University of Pennsylvania

to study that and then moved to New York. So a lot of the stuff that I

am doing is grounded in the different types of music I heard growing up

in Philadelphia.

FJ:

Did you separate the music into two genres, classical and jazz?

URI

CAINE: I didn't necessarily see them that way. Obviously, there is a difference

between sitting in a concert by the Philadelphia Orchestra and then playing

on Saturday night at a jazz club. There is a definite different atmosphere

in the way that people are relating to what's going on. If anything, I

was determined not to be discouraged from dealing with music that even

people within the groups that I was playing with were saying wasn't worth

it, like if I was playing with a bebop cats, they would say that out music

wasn't happening. I would think to myself that I was into out music or

when classical musicians would say that they don't really give it up to

jazz musicians and that it was not serious, then I would just laugh and

think that it is totally serious and the fact that different people did

not endorse other types of music. Even though they were musicians, it

didn't discourage me from checking out what I wanted to check out and

hang with who I wanted to hang with and sort of absorbing what I wanted

to absorb.

FJ:

Sounds like you were a rebel.

URI

CAINE: I guess if that is, although I think that a lot of musicians are

in that same boat. I think even musicians who, if I go on the road, I'm

sort of shocked or not shocked, but pleasantly surprised by what people

are bringing out to listen to and it really covers a wide gamut. I think

this whole idea of putting things into categories, it works for certain

things, but in terms of just the general passion for music that a lot

of musicians have as fans as well as players, that they can absorb a lot

of different things and want those different things. I mean, it is not

eclecticism for sake of eclecticism. You hear some stuff that knocks you

out and you start checking it our and then you realize that there is music

behind that music and then there is music that came before that music

or was influenced by that music and so it becomes this really wide pot

that you are dealing with. I prefer to look at it that way. I was also

made aware when I was younger that there was a lot of different styles

and in a sense, if you are playing with Philly Joe, that is a different

aspect of playing and you have to bring a different set of skills sometimes

to different aspects of music making, but that is a different story than

what you are actually absorbing or rejecting.

FJ:

What were some of the interesting things you heard?

URI

CAINE: I went through a lot of different phases, but I know that I was

really obsessed with Miles Davis and John Coltrane, especially Coltrane,

having lived so much in Philadelphia and hearing first hand stories about

what type of musician he was. I went through a heavy phase of that. I

went through a really heavy phase of a lot of contemporary music like

Stravinsky, Boulez, Bartok, because when I heard it, it sounded so fresh.

I guess coming from different, when I grew up, I grew up in a house where

my parents spoke Hebrew to us. They were playing a lot of Yeminite music,

so that sort of had an effect. I guess another thing was when I was starting

to study composition, my teacher was saying to me that I really had to

go through a lot of the older styles and try to write pieces in those

styles and to sort of understand choral works or how a Mozart sonata works,

and so it forced me to investigate that music. Even though initially,

I just took it for granted, the more I got into it, the more I became

into it. I was really into gospel music, just any type of music that had

either a strong emotional in it, but also had interesting structure, interesting

architecture.

FJ:

I am curious as to how a classically trained pianist gets into Trane.

URI

CAINE: Well, I think it he was risking alienation and still he was going

further and further in his explorations and you get a really strong feeling

of somebody with a spiritual path and trying to find release through music.

I liked that idea. I think he exemplified that. Also, his music, in terms

of where he took what he started from and where he took it. It always

seemed like this really towering achievement. It was so passionate, the

way he played, and I was really attracted to that.

FJ:

Do you find yourself on a spiritual path, much like Coltrane was?

URI

CAINE: I do, but I would not compare myself to him. But in the sense that,

yeah, there is a certain obsession for music that is really just a metaphor

of drowning yourself in something in order to see what happens. Also,

music is a lot of fun to play and to talk about and to think about and

that is why so many people are drawn into the whole vortex of it. But

in terms of something that I think about a lot and care about, yeah, I'm

definitely into that.

FJ:

When did you venture into New York?

URI

CAINE: The late Eighties.

FJ:

What was the climate for creative improvised music at the time and how

have you seen it ebb and flow over the past decade?

URI

CAINE: There is always this idea that there are somehow these separate

scenes. There is a downtown scene. There's an uptown scene. There is sort

of this young lions scene, which I guess was sort of pretty important

in a lot of people's minds then. For me, it was again, it was never a

question of these ideologies. It was more a question of, first of all,

the practical aspect of how do you get started. How do you gain a foothold?

It was really, for me, a lot of scuffling. I started playing with Don

Byron in 1990, which is an association I still have and in a way, took

me into a lot of different types of music that he was playing as well

as starting to play with a lot of different schools in New York. At the

same time, I was playing with people like Buddy DeFranco and Terry Gibbs.

I was also playing with Sam Rivers and Barry Altschul. So, again, it was

like one of those things where somebody could say, "How can you deal with

both?" And the thing was, since I knew where that music was coming from,

it was no problem for me because I had played all that type of music before

and wanted that type of variety. It was very gradual. I was playing a

lot at a place where they would have this really late night jam sessions

and I was meeting a lot of horn players that way. I started also playing

with other guys like Dave Douglas and a lot of the people that people

now think of as the downtown scene around the Knitting Factory because

in a way, that was the only place that we could play if we were playing

improvised music that wasn't totally straight ahead. There weren't that

many clubs in New York. There still aren't that many clubs in New York

that really have that type of music. In retrospect, I can say that I was

part of that as well. I made my first record for JMT, I recorded it in

'92 with a lot of the people in Don's group, Ralph Peterson and Kenny

Davis. I was playing with Gary Thomas on there and Graham Haynes. I guess

I was playing with some of the guys that were supposedly part of that

M-Base thing. In reality, I think that it is a lot more fluid than that.

I think that a lot of musicians have a lot of different types of associations

and it is not to say that there aren't these different styles, but I think

it's a lot more complicated than that and for me, I find that I end up

playing with people from a lot of these different schools just because

we want to play together. It's not so rigid.

FJ:

It isn't cookie cutter jazz.

URI

CAINE: Yeah, I think that like most things, it is more complicated than

it seems.

FJ:

Let's touch on your association with Don Byron.

URI

CAINE: He's a great musician. I think that he has an openness and a curiosity

about a lot of stuff. For me, it is always funny that I started playing

klezmer music with him. I'm Jewish and supposedly it is part of my background

and I never really played it. I heard it, but I wasn't really into it.

I started playing it with his group. I know he's into a lot of types of

music like early Duke Ellington and a lot of the swing music, as well

as a lot of other types of stuff, Stravinsky, so we sort of have that

in common that we are really sort of interested in a lot of these different

types of things. I think that type of openness and desire to pursue stuff

that wouldn't be expected makes working with him fun. It leads to a lot

of variety. Some of his groups might be more in like the Bug Music, Duke

Ellington vibe, so I play a certain way that way. If we are playing in

a group like Existential Dred, which is much more like a funk-rock driven

type of thing with poets. That is a different feeling. I've also played

in groups playing straight ahead, twentieth century contemporary music,

so that is a different thing. Throughout all those different projects,

there is this feeling that we are going for something and to me, it is

interesting.

FJ:

Your association with JMT, led to your continued involvement with Winter

& Winter, where you recorded the Mahler project, Primal Light.

URI

CAINE: That was recorded in '96. It came about because I had gotten on

JMT during the last couple of years of its existence, already when it

was being subsumed by Polygram. So I guess when it became clear that that

was going to end, mostly because they shut it down and Stefan (Stefan

Winter) started a new label. Projects like what I have been doing on Winter

& Winter sort of became more possible because there wasn't this overhang

of the corporate, you have to make a record that somehow can be sold and

dealing with that whole issue of what it means to make something that

a record company executive thinks will sell. It came about really when

I was mixing the second record I made for him called Toys, which had this

Latin piece on it, where one of the bass lines was a quote from Mahler's

first symphony. When I mentioned that to Stefan Winter, he told me he

had just made a television film about Mahler, which was with no words,

just images from Mahler's life and places that he had worked and there

was a Knitting Factory celebration of JMT, which had many of the artists

on JMT performing with their groups and this was going to be one of the

projects. He asked me to put together a live group, playing together to

that movie. So after that happened, I decided to sort of expand it. That

was how that first record was made. It was basically an expansion of that

initial concert, where I took Mahler's music and sort of rearranged it

or re-imagined it and using a lot of musicians who I was already playing

with in New York as sort of a way to reinterpret his music. So that was

the genesis of that. It was sort of a different direction for me, but

again, it was something that I had always, I had been listening to Mahler

since I was fifteen and then studied his scores. I was sort of interested

in seeing how a group of improvisers could reinterpret music that was

being perceived as being one genre.

FJ:

You used the services of DJ Olive, do you see the turntables as an instrument?

URI

CAINE: Of course, I think it's a, whether or not, when you say that word,

instrument, it's of the same type of instrument as a violin or whatever,

it maybe it maybe not, but the point is, the effect that I liked that

it produces is dislocation. For instance, in that project, if we are playing

Mahler and then the DJ brings in his own version of Mahler, that counterpoint

can be really beautiful. I'm just really into that music. I think that

I'm not so hung up on how it's produced or whether or not this instrument

or that instrument is producing it. I guess for my point of view, all

these things are machines on some level and so they're used to express

music, it's fine.

FJ:

You have taken the Mahler ensemble on the road and the Mahler in Toblach

reflects that.

URI

CAINE: Initially, again, I think there were certain promoters that were

saying that it was too many people and it's too weird, but we have been

playing it a lot, especially in Europe for the past two years.

FJ:

And the audience response?

URI

CAINE: It has been very good. Of course, there are people that don't like

it and people that are offended, but when we played in Salzburg last summer,

I think it was an emotional response. I just think that there are certain

concerts that really standout in my mind with people who are ready for

it. In a sense, it just intensified that music for them, but it's not

universally accepted. I'm sure a lot of people have problems with it for

many reasons.

FJ:

What are some of those reasons?

URI

CAINE: I think it's either that Mahler already did what he did. There

is no need or reason and it's almost like an arrogance to do that to his

music, which is sort of ironic because Mahler throughout his life was

accused of doing the same thing. He was adding trombones to Beethoven

symphonies and justifying it by saying that if he was alive today with

these new instruments, he would have used them and I'm just rewriting

it because I want it to sound more powerful. I think a lot of people have

problems with improvisation, with jazz improvisation, specifically, if

they are based in classical music. I think a lot of jazz people have problems

with playing classical music and all this business of diluting music by

trying to match them or mismatch them that you end up doing neither. With

all those risks inherent in it, I still, I think it can work. I'm coming

from it from the point of view of a jazz musician, in the sense that we

are taking a text, just like we would take an Irving Berlin song or a

George Gershwin song or even now a Herbie Hancock song or a Wayne Shorter

song and improvising with it. What that means is that you are transforming

it. I mean, Irving Berlin did not like Billie Holiday was singing his

songs, but in a sense, those interpretations of those songs immortalized

those songs. I know a lot of the times there is a lot of ambiguity on

how all these things work and for me, I'm looking at it from a selfish

point of view as a musician playing in groups a lot. I want to play this

great music, but also use it as a springboard for improvisation and get

to set up a group process where we are playing these pieces almost like

a Mahler symphony because that is how we play it. We play like a ninety

minute, sometimes even longer, just a continuous version to give this

feeling of this grand piece, which is going through all these different

moods.

FJ:

And the future?

URI

CAINE: I have a lot of stuff coming up with this CD I made based on Bach's

Goldberg Variations. It is taking the idea of the variations and have

the greatest amount of contrasts between short pieces, but have it all

be unified by a centralized theme, which is what all the great variations

did. So I chose the Goldberg Variations because I was always deeply influenced

by Glenn Gould when I first heard him playing that piece. The Goldberg

Variations themselves are sort of this compendium of Bach. He wrote it

at the end of his life and he's dealing with a lot of different national

styles with dances and he even has drinking songs at the end, which he

combines and he has canons at all the intervals. In a way, I just took

all those things and played the variations in many different arrangements

from a baroque group to a choir to solo piano to even electronics to having

sort of a drum and bass feel to it, to also writing thirty or forty variations,

but instead of Bach writing, I might put in a mambo or a tango and also

have a lot of pieces that refer to Bach's music, chorals and solo cello

pieces and also tributes to other composers and their styles. All these

pieces are based on the harmony of the original theme.

FJ:

And the release date?

URI

CAINE: That is due out in Europe probably in a month and in the United

States at the end of the summer.

FJ:

Do you think there will be a time where you will have reached a pinnacle

as an artist?

URI

CAINE: No, because I don't know if you can ever say that. It sounds like

a cliché, but as soon as you do something, again, it is that Coltrane

thing. You are never satisfied with whatever you do. It's hard.

FJ: It seems like a lot of perpetual angst.

URI

CAINE: But it isn't. I'm not like a writer that has to sit in his room

for two years to write a book. We get a chance to play and to travel and

the art form itself is a very interactive one. At its best, if the groups

are really interesting, it is not necessarily lonely, but you are right,

you are never really satisfied because things could always be better.

At some point you have to say that the record is done or the piece is

finished, but then you hear it and then you say that you should have done

this. I definitely feel that about a lot of the stuff that I have done,

but I know that that is the nature of it and even my own reaction to it

changes and so I tend to accept that and tend to not worry about it so

much. Learn from your mistakes and keep on going.

Fred

Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and never made it past the fastest fingered

question. Comments? Email Him.