A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH BOBBY BRADFORD

Bobby Bradford has played with Ornette Coleman. He has long been a favorite

of mine. I recently saw Bradford play with his quintet at the Knit in

Hollywood and with Arthur Blythe and he was el fuego (poor Sportscenter

reference). May I present Mr. Bradford, unedited and in his own words.

FRED

JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

BOBBY

BRADFORD: Well, I grew up in a neighborhood, from around age eleven in

Dallas, Texas. There were some professionals or ex-professionals who lived

in the area, people who were retired musicians. T-Bone Walker's father

lived in the neighborhood where I grew up in. There were a most of musicians

around town who were older than me, maybe five, six, eight, ten years

older than me, who played around town on the weekends in the various clubs

and juke joints. So, in the community that I lived in, I could hear these

guys practicing at home and pass by their places and hear them playing

records of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie when I was a fourteen year

old. I had heard jazz before because, of course, my father was a big jazz

fan. He liked the big bands though. I wasn't particularly taken to jazz

and interested in playing with big bands, the swing style. What drew me

to the music, to want to play it, when I was inspired to play, was when

I heard Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie, and Miles Davis, and Fats

Navarro, the beboppers. That is what drew me into the music.

FJ:

What made bebop so special?

BOBBY

BRADFORD: Oh, man, Fred, that's a biggie. Bebop had, in addition to the

vocal quality that all jazz music seems to have as a general statement,

the New Orleans' style of Louis Armstrong and the swing era of Lester

and Coleman Hawkins and all, but bop had an urgency about it. It was more

polyrhythmic and in my ears, it was a more sophisticated music than swing

or the New Orleans style, but that would take some talking about because

of course people could say that you couldn't be any more sophisticated

than Louis Armstrong. But the boppers were, as a general statement, technically

more proficient than the swing or New Orleans players. What added to it

about the boppers was the new social posture of the beboppers. There was

no clowning around. They had that sort of pseudo-intellectual air. That

was part of it too. They had their own language and dress code. It was

so hip (laughing) for want of a better way to say it.

FJ:

So to be cool, one would naturally play bebop.

BOBBY

BRADFORD: Oh, yeah, growing up, as far as I was concerned, there was the

Louis Armstrong bunch, which we sort of took for granted because we didn't

have sense enough to know how important Louis Armstrong was, at least

I didn't when I was twelve years old, and then there was the swing group

with Basie's band and Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young and I knew who

those people were. When I started to play the cornet, which I started

on in what would have been junior high, but we didn't have junior high,

we went up to grade eight in elementary school and high school was nine,

ten, eleven, and twelve. I started to play the cornet when I was in tenth

grade and bebop was the thing. That would have been around 1949 or '50,

when Charlie Parker was at the peak of his powers. That is when I started

out trying to play, trying to play like Dizzy and Miles and Fats Navarro

and every trumpeter. As I began to get a handle on that, that was right

in the middle of course of the coming of the cool jazz thing, especially

the big West Coast version of it. And then the Miles Davis thing of 1949,

that didn't somehow manifest itself to us in school until over into the

Fifties, even though and those guys made that first record (Birth of the

Cool) in 1949. At least as far as I was concerned, I didn't really grasp

the cool jazz sound of that Miles Davis bunch. I am not talking about

here like Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan. The Miles Davis cool jazz session

of 1949, that was a big, monster event.

FJ:

Did that change your conception of bebop?

BOBBY

BRADFORD: That didn't change my idea about bebop, to me that was just

a softer version of bebop. I still thought of that as bebop because of

the chord changes were all pretty much the same. The melodic lines used

the same chord alterations. It was just in my mind a softer version of

bebop. That is the way I always heard that. In my mind, there wouldn't

have been any cool jazz if there hadn't been a bebop. I just saw what

Chet Baker played and Gerry Mulligan played and the guys on the West Coast

as a less aggressive and less emotionally intense style of bebop. In other

words, in my mind, Chet Baker was still from the Miles Davis perspective.

That approach to playing the trumpet, that cool, laid back, almost no

vibrato, interesting kind of attack, unlike Dizzy and Fats and all those

really gymnastic kind of players. That still had the articulation of the

bop style. So the West Coast players to me, and I liked a lot of them,

Art Pepper, to me, was an interesting mix of Charlie Parker and Lester

Young. There is two big routes in bop trumpet. There is the Gillespie

route, which you would hook up with somebody like Fats Navarro too, even

though they both had their own distinct styles, they both were really

powerful trumpet players with super range. Then there is the other camp

of players who didn't play so high or so loud and didn't have the range

and power. Chet Baker and Miles Davis went the other route, the cooler,

more restrained player, but it was still bop. I still see Chet Baker as

a bop trumpet player, just more restrained and a softer approach than

somebody like Dizzy or like Fats Navarro or like Kenny Dorham.

FJ:

What route did you take?

BOBBY

BRADFORD: As a kid, I grew up trying to play the best I could get from

all of the boppers. I was trying to learn how to create that bebop melodic

line originally, so I learned just as much listening to the tenor players

or piano players as I did the trumpet players. Early on, like all the

kids, I was trying to copy solos from Dizzy and Miles and Fats Navarro.

When I started trying to figure out something that was Bobby Bradford,

I don't think you could put me in any of those camps. I'm in my sixties

now and I don't play with the kind of power as I did when I was thirty

years old. I've never thought of myself as being like a Dizzy kind of

trumpet player with that kind of power and range, playing all those altissimo

notes on the horn, but then I wasn't a restrained player either and just

stayed cool and laid back all the time. Whatever national attention I

got came via my playing in association with the so-called free jazz. I

had no reputation as a bebopper. But I could say I was a good bebop player.

I could get up there and play. I knew all the bebop tunes. I knew how

to play "Cherokee" and "All the Things You Are" and Monk tunes and "Round

Midnight." I knew that because I grew up studying it. Leo Wright and I

were roommates in college. Leo was very precocious. This guy was smokin'

man. As a freshman in college, Leo was killing. The rest of us were scared

to death of him. He was so mature at that point as a player. He was clearly

a professional already when he got to college. We were all still trying

to get a handle on playing those complicated chord progressions.

FJ:

Being involved in the Los Angeles scene in the Fifties, you had an opportunity

to play with both Eric Dolphy and Ornette Coleman.

BOBBY

BRADFORD: After spending a year and a half in college with Leo, we both

left college at the same time. In the summer of '53, I moved to Los Angeles

where I ran into Ornette Coleman. I had met him in Texas, but not as a

musician. He just happened to come to the part of the neighborhood where

I lived because he had a close friend there. I knew about him. I didn't

really know him. He came to Los Angeles about the same time that I did.

We were all around town then playing jam sessions, which included the

California Club at Santa Barbara and Western. That used to be a Monday

night jam session. We were all running around town and we were all roughly

the same age. Ornette is about four or five years older than me and Eric

was probably around maybe three or four. Eric had just come back from

the army and he was still playing the alto saxophone and the clarinet,

which he played in the army. He was still playing everything that he could

get from Charlie Parker. He was not playing any free jazz, nothing even

close to it. There is a lot of people who would argue with that, but I

was there. We would meet at these sessions and we would spend days, sometimes

we would rehearse at Walter Benton's place because he had a garage with

a piano in it. Most of us were interested in transcribing saxophone and

trumpet solos from the recordings because that gave you some insight into

what some of these guys were playing and how they developed their linear

styles. There was no books. There were no schools. There were no Jamey

Aebersold records. There was no place to go and study this stuff. All

you could do was just listen to the records and get what you could from

that and if there was somebody in town who was a professional, try and

get some lessons. Most of us were just trying to figure it out from the

records. We would get together and work on these transcriptions and check

them for accuracies and inaccuracies. We would see each other around town

playing at these various jam sessions. There were half a dozen places

around town that had regularly you could go in and play, unlike now. We

would come in around eight or nine and play until twelve or one at night

and we saw each other a lot. We studied together sometimes, but Ornette

and I having met in Texas, I ran into him one day on the red car, the

old trolleys that we used to have here. We renewed our acquaintance. He

asked me if I would be interested in going over some of his tunes and

playing it. I would go over to his place and we would go over his tunes.

The times that I would play with him, we would play a complete three sets

of his tunes and the stuff was pretty scary, but he was still playing

standards at the time, in addition to the stuff that he was writing.

FJ:

Let's talk about your time with Ornette Coleman.

BOBBY

BRADFORD: When I went to New York to play with Ornette Coleman, I had

spent already three or four years in military bands during the end of

the Korean conflict. I was in the service at that period and I played

in military bands. If we had jazz bands, which we did, the guys in there

were mostly playing bebop. There was nobody playing free jazz. I had played

with Ornette, here in Los Angeles and had been exposed to that new concept

as early as 1952. Getting a handle on that was no easy task because there

was only so many places you could play like that. There were only so many

people trying to work that out with you. So when I came back out of the

military, I went back to college and Ornette, I suppose, had remembered

that I had played with him here in Los Angeles and I understood on some

level what it was he was doing and had been toying with that too when

I was in the military, but still playing bop tunes. We had jazz bands

that traveled around and entertained the rest of the troops and we were

basically still playing the music of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie

and the beboppers, although, I was still pursuing this concept of trying

to play melodic lines without referring to chord progressions. So I rejoined

Ornette Coleman in New York in 1961.

FJ: Early on, there must have been a good deal of resistance to free jazz.

BOBBY

BRADFORD: Oh, yeah, Fred. He especially. He would sometimes go out to

the jam sessions and they would be playing standards and he would go onto

his free thing and try to play that stuff over and above or against what

they were doing. Now, he clearly knew how to play "All the Things You

Are" and the Charlie Parker tunes in the conventional way. I can remember

very clearly playing with him and we were doing "Stardust." He was playing

beautifully and not playing anything that you and I would call free jazz.

But in the course of the evening, we would play one of his that was totally

free. Now, it wasn't quite like that record of his, Free Jazz. This stuff

was just two horns, bass, and drums and if he had a piano player, the

poor piano player would be trying to figure out what to do and on some

nights he did. By the time Ornette got to New York, he had already made

one record here in Los Angeles. They were playing those lines of his that

was very bop-like, but he was trying to play them without following any

chord progressions. Walter Norris was having a real problem with that.

I remember talking to him about that once. He said something really interesting.

He said, "I don't think Ornette knows his own tunes." (Laughing) Well,

by the time Ornette got to New York and made that Free Jazz thing in 1960,

I guess it was, all the connections between him and bebop were gone by

then. There hasn't been any looking back since.

FJ:

Did you know it would change the face of convention?

BOBBY

BRADFORD: Well, I knew he was onto something back here in Los Angeles.

Here he was the outcast and I wasn't going to fool with him unless I was

going to get something out of it. I heard something in his music. I had

no idea whether he was going to get to be a big star or not, but I wasn't

interested in that anyway. I heard something valid in his music, which

I wanted to access as best I could. Here was a guy who had something to

say, who used the Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie tools to say it.

It was always clear to me that this guy had a great story to tell and

he can only tell it his way. But I knew he was onto something the first

time I ever heard him.

FJ:

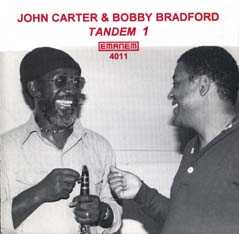

Let's touch on your association with John Carter.

BOBBY

BRADFORD: Well, everybody in this bunch we are talking about is Texas

people. I didn't know John in Texas like I do Ornette. John is from Fort

Worth and I am from Dallas and they are almost twin cities, they are so

close together. I had never laid eyes on his until here in California.

We both found ourselves in similar situations with families and wanting

to play jazz, but having no opportunities to play what we wanted to play

here in Los Angeles. I had come here after leaving the Ornette Coleman

band in 1963. I was living out in the Pomona area and John had been teaching

here in the city schools. He was mostly playing alto then, although he

was originally and always a clarinet player. The jazz thing, he was playing

mostly alto. He and Ornette were still in touch and for some reason came

to Los Angeles and John was saying how he was thinking about organizing

a band here and he would like to hook up with guys that were interested

in similar things and so Ornette told him to call me. Finally, John called

me and we had a meeting and decided to organize a band. That was the beginning

of the New Art Jazz Ensemble. We used to rehearse Tuesday and Thursday

nights for ages we did before we ever got our first job. We had been rehearsing

for probably a year. We got our first job at a little place called the

Century City Playhouse. There was no money involved, but we were playing

our own music, either written by me or written by John. We kept that group

together until about 1970, '71. Bob Thiele came to Los Angeles, apparently

trying to see what was happening and we auditioned for him and we did

two records for Flying Dutchman in 1970 and '71. At that point, we thought

that we were getting such good reviews from this and this is going to

take off. Nothing happened. We got jazz record of the year in Japan and

got five stars in this magazine and four and a half in that one and we

thought that this was it and we were on our way. Everything went right

back to where it was. Bob Thiele told us that if we were to get anything

more done than we were doing now, we should move to New York and neither

of us were willing to do that. I had already been to New York with Ornette

and it was clear to me that I did not want to go back there with my family

and try to make a living playing jazz. I didn't want to do it and John

had never been there working and he didn't want to break up housekeeping

here with a wife and four kids. We just thought we would stay here and

make something happen for ourselves. Nothing did and we were playing around

town, but we couldn't play Howard Rumsey. They kept saying how they liked

how we played and all, but no one was going to come here and hear that.

FJ:

Yet another reason for me to be ashamed of Los Angeles.

Fred

Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and is the fifth Beatle. Comments?

Email

Fred.