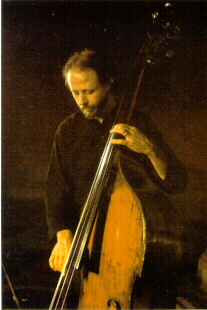

Courtesy of Barre Phillips

ECM Records

A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH BARRE PHILLIPS

I am in awe of Barre Phillips. And anyone who can play the bass like he

can, we should all get in line to sit beside them hoping that some of

that will rub off on us. So closely associated with the success that ECM

has had through the years, Phillips has aged well musically. I am honored

to bring to you (perhaps by reading this, some of what he has will rub

off on you), Mr. Barre Phillips, unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

BARRE PHILLIPS: I grew up playing jazz, starting with Dixieland and classical

music and I was always so excited playing those music, I kind of played

my own thing. At the end of the Fifties, when Ornette Coleman came on

the scene and said that that is what we're supposed to me doing, is playing

our own thing and that was the message for me.

FJ: So Ornette was pivotal in your early development?

BARRE PHILLIPS: Yes, it wasn't so much the music, which I loved very much.

It wasn't a big discovery, the music itself. It was what he was talking.

It was what he was saying with his words when you would talk with Ornette

because I met Ornette in 1958, I mean, personally. It was actually four

years later when I re-met him after he had made all those initial records

and everything. I met him again and he gave me the message and I was ready

for it (laughing).

FJ: What was the message?

BARRE PHILLIPS: The message was, well, in detail, as far as antidotes

go, Fred, he came and sat in with a band that I was playing with out in

California. He had been in New York for about four years at that time.

He was out on the West Coast again. I was still on the West Coast and

he sat in with us on a friendly basis. We were just playing standards

and what was acceptable in the jazz repertoire at the time and he said,

"Well, you guys played great. How come you're playing this school

music? Why don't you play your own music?" And I was ready for the

message.

FJ: Why did you decide to pick up the bass?

BARRE PHILLIPS: It's a long story, Fred. Actually, the bass chose me.

I have to say it like that. I started at thirteen years old in public

school, in junior high school. When they were going around looking for

people to fill up the orchestra and they said the bass, I had a vision

and my hand just flew up and that's how I started playing the bass.

FJ: A vision?

BARRE PHILLIPS: The vision I had, if you are interested, the vision was

I saw my name on a theater marquee. It was so strong that my hand just

automatically flew up and I saw the actual, real life theater marquee

in 1980 in Milan, in Italy. I'd saved that memory all those years, not

looking for it, but it was there (laughing).

FJ: How have you made use of your degree in Spanish?

BARRE PHILLIPS: It's been very useful in, not necessarily the Spanish

because I live in France, but to have studied a lot of Spanish and Italian,

it made it really easy for me to learn French, which I didn't study in

school (laughing). But I think it's more the having been in university

and working on communications. That has been a great background for me.

It has to do with the twenty-five years ago, for the first time, somebody

asked me to teach a workshop. I was already an improviser and basically,

or at least at that time, at least half of my public performance was free

improvised music. Today it is much closer to a hundred percent is free

improvised music. So the question of what's going on, now how does an

education when at you're at the university and you are trying to learn,

they are trying to teach you how to think and whatever university you're

at, it's in some kind of a mold. It's in some kind of a form because you

have to try and teach things. But in language, I was working in philology

and after, because I did a couple of years of graduate work after my bachelor's

in philology and you try and learn how to piece together how people communicate

to each other and I was very much into that in the raw materials, but

with musical sounds rather than language sounds. And so it's a matter

of finding the words that try to define what's going on in feeling and

communication when this music is happening, when this improvised music

is happening. And so I've been working on that for twenty-five years now.

I haven't written a book yet, but since I'm taking a sabbatical next year

to start writing on the book. It'll get there one day.

FJ: At the close of 1968, you recorded a notable work entitled Journal

Violone, recorded in a church.

BARRE PHILLIPS: Yes.

FJ: It has gained quite an underground cult following through the years.

BARRE PHILLIPS: Really? Well, at the time of the original recording, which

was recorded in 1968, I didn't even know I was recording for an album,

so what you have there are my musings as it were, my musings and playings

just to put what I could play on the double bass down on tape. That was

the original objective and the man, who was the owner of Opus One and

he had proposed this project to me. Then he said after that, "I want

to make a record out of it. This is fantastic. I want to make a record

out of this." Then I had to get my head around from the position

of "I'm just doing this because this guy wants to hear what you can

play on a bass because he's a friend" and get into this no, he wants

to make an album. I have to get my head into the thing so I can do that

and I can allow this to come out because I don't know if it is any good

or not or whatever or what it is. And that took me quite a few months

in working on that. It is kind of a historical record, Fred. It is the

first solo record that was ever recorded of free music. I didn't know

that at the time. I found that out three or four years after the album

came out.

FJ: Can the bass, as a solo instrument, be appealing enough to hold the

interests of today's audiences for any significant length of time?

BARRE PHILLIPS: To the general public, well, there are guys who do that

for the general public. You don't see them on the top forty, so you have

got this whole problem of defining what is general public. But a concert

going public of classical music, there are soloists in classical music

like Duncan McTier, an Englishman, and others, who are so fantastic that

they have a solo career with the big orchestras and in the big venues,

not as much as the big violin players or Rostropovich (Mstislav Rostropovich),

but they have been able to earn a much more of a decent living as a solo

bassist in the classical realm. You'll find the same thing for the jazz

public. In terms of a pop public, how many people know that Sting is a

bass player? Is it dead already in the techno scene with bass and drums.

It is not anybody. It is not some great player playing the bass and is

playing this fantastic stuff. It is just some workmen doing the things.

FJ: Let's touch on your relationship with Manfred Eicher.

BARRE PHILLIPS: I met Manfred Eicher in 1969 or '70. I actually met him

before ECM was created. We met. He was a bass player playing in a jazz

group at a club in Berlin. We just went to the club after the concert

and met the guys in the band and Manfred and I might have talked for two

minutes or something. A few years later, I was recording with Dave Holland

in German radio, a big project, which turned out to be the record, Conflagration

(Dawn), which is one of the old Trio records from our old stuff from the

early Seventies. Anyway, Manfred came up and said, "Hi, how are you

guys doing? Remember me?" "Oh, yeah, how you doing man?"

And he proposed to us to record the duo record, which is Dave Holland

and I called Music for Two Basses (ECM), which is about the third record,

second or third record on the ECM label. And then I knew he had a record

company and I actually didn't go back and proposed that we had to record

until some years later, in pretty much 1975 and then we recorded in Early

'76, which was the record, Mountainscapes.

FJ: It has been a fertile partnership that has lasted well over a quarter

of a century.

BARRE PHILLIPS: Absolutely, for me. And I think since we are still good

friends and talk to each other (laughing), it must be OK with Manfred

also, yeah.

FJ: He must be an asset in the studio having been a bass player himself?

BARRE PHILLIPS: Well, he has, I wouldn't just say helped a lot of other

interesting bass players along the way, which is normal, but he also likes

guitar players. He has record a lot of guitar music through the years.

What is so fantastic about Manfred Eicher is his integrity to himself.

He started this label, found the backers so he could start, all on doing

what his version of what a record company should be and not his version

of how to make a lot of money.

FJ: A forgotten theme, it seems, these days when money has become a drug.

BARRE PHILLIPS: The money is there. To keep alive, you have to keep growing.

I'm sure that there is money that flows through that thing, but he's recorded

so many records like, I don't earn money for ECM overall. I must be on

sixteen, seventeen, maybe eighteen albums for ECM through the years, whether

they're my records or collaborating with somebody else. I'm not making

money for ECM, but Manfred Eicher has been supporting my music and my

playing all these years by recording me. That is what I mean by supporting,

not sending me a monthly check, I don't mean that. By recording my music,

he's been supporting me on what I do, which is fantastic. Unfortunately,

you don't see that happening in the States.

FJ: You appeared on a posthumous GM Recording's release of Eric Dolphy's

entitled Vintage Dolphy.

BARRE PHILLIPS: That was not Eric Dolphy came and asked me, "Can

you play?" It was a matter of circumstance in that I was hired by

Gunter Schuller to participate in his contemporary music series in New

York City, when I finally got to New York City in the early Sixties and

Dolphy was on the gig. Well, our playing together was involved of playing

in a medium sized orchestra. He played a solo piece of abstractions and

on that record, the other piece that's on there was an encore piece for

the concert. The tapes that are on that Vintage Dolphy are all stuff that

was never made for record, but recordings that were made in clubs and

copies of concerts that were done by Gunter Schuller.

FJ: What prompted you to make your way into New York? And was it all you

had anticipated?

BARRE PHILLIPS: After I re-met Ornette and he said, "Why don't you

make your own music?" I knew that I had to go to New York because

that's where it was all happening. Compared to what it is today, first

of all, the economics were very different. You could still be poor in

New York. You could find, I never paid more than a hundred dollars a month

for rent, for example, and play at a dumb gig at a club for ten bucks.

So you could earn a living as a musician if you could play and you weren't

too weird. You could earn a living as a musician, pay your rent, even

have a family, and be poor, but you could get by. You can't do that anymore.

It is a huge difference now. You've got to have a thousand or twelve hundred

dollars a month and a dumb gig at a club is twenty-five bucks and not

ten anymore. Things haven't gone up in the wages the way they've gone

up in the costs. So there was a lot of people, it was a historical moment

in New York and the contemporary music scene, there were an enormous amount

of concerts in Town Hall. There was a whole happening scene that was still

going on. I got to New York in 1962. I am talking about '62, '63, '64.

I met Don Ellis very quickly. He was doing a lot of experimental music

and an experimental workshop every week. It was a very open situation.

I did my first trials with abstract composing and stuff in those workshops.

We were playing at home all the time with all kinds of different people.

There was very little work for this new music. There was very little work

for us. In 1965, when I was playing with Archie Shepp in New Thing at

Newport, was the first time that there was some free music at the Newport

Jazz Festival, which was the official jazz festival at the time. There

wasn't nearly as many festivals in the Sixties as there are now today.

But Newport had been going on and in 1964, I traveled to Europe for the

first time in the George Russell Sextet, which was avant-garde jazz. It

was the first year that there had been any American avant-garde jazz come

over to Europe in an official tour, doing the big festivals and stuff.

So it was a historical moment and I was there. I was a young bass player

and I guess the people liked the way I played. I toured Europe in '65

with the Jimmy Giuffre Trio, which was the old Free Fall trio.

FJ:

Steve Swallow is the bassist on record.

BARRE

PHILLIPS: Well, I played with Giuffre just after that and toured Europe

with him. It was fantastic. He was a real searcher for how to make music

and he found a lot of stuff. He lived just ten minutes away by foot, down

the street from me and I was over there every possible minute over two

years time when I wasn't working or doing something else because he basically

had no work at the time. He was very available. Free Fall didn't sell.

Free Fall was on Columbia Records (reissued on Columbia/Legacy), which

Jimmy Giuffre had access to from his older music, from his older standard

jazz stuff. But since it didn't sell, it didn't do anything on the market,

he lost his contract and he lost all his connections. He went through

some years of difficult financial times not earning any money. That is

the Jimmy Giuffre story. Anyway, he was an extremely creative man, very

open to things, and I learned by osmosis playing with him an awful lot.

They just released, here in Europe, a recording of a live concert that

we did in 1965 in Paris. It was very interesting for me to listen to that

music from thirty-five years ago.

FJ:

You've had a valuable association with avant superhero Peter Brotzmann

as well.

BARRE

PHILLIPS: Yes, Peter, we've known each other from when I first started

living in Europe at the end of the Sixties. We've never made a band together,

but there is the FMP recording of concert music in trio with Gunter Sommer.

There might be some old things from the old days with these big collective

groups, but in terms of actually playing together, there is only one recording.

FJ:

Why did you leave New York to make permanent residence in Europe?

BARRE

PHILLIPS: I read into some information on London and I came to London

and I was going to stay for two months and do a little research completely

outside the music scene. It was at the end of a tour with a guitar player

and so I got to London after the tour and I'm going to stay for two months

and I start meeting all these musicians. I met all the guys from the Spontaneous

Music Ensemble: Evan Parker, Derek Bailey, John Stevens, the drummer,

and Trevor Watts. I met all those guys right away and they said, "Oh,

great. A bass player. We've haven't had a bass player in years."

And so I started playing with them while I was doing my thing and that

led to things like Marion Brown calling me from Paris and we come and

play. We knew each other from New York and from being around Shepp and

Coltrane. I started getting all these work propositions and I kept calling

back to New York saying that I was going to stay for another month, keep

my apartment, I'm coming, I'm coming. So I didn't leave New York. I came

over here for something else entirely and then I got a proposition to

play in a movie and do the score for a French movie. I wasn't about to

go back to New York. And one thing just kept leading to another where

the creative work over here in Europe that was proposed to me and that

I accepted and did, replaced the professional work that I was doing in

New York City.

FJ:

Having been in Europe for a considerable length of time, what are the

not so subtle differences between the two shores?

BARRE

PHILLIPS: Well, there are two main, big differences. One is funding. All

over Europe, from country to country, it is different and from region

to region inside the country, it is different, but there is public money

for art, for creative art, for new art. There is public money for a lot

of other kinds of art like keeping up the old art, keeping the museums

together and all that and the orchestras alive and everything. There is

a lot of public money. That is one big differences. The other big difference,

we are talking in the European union now, which is like central, the center

of Europe, ten or eleven or twelve countries that you could stick the

whole thing in the United States with no problem at all and there is still

a lot of United States left over. The country of France is the same size

and population as California. So you have all these markets in a small

geographical area, compared to what you have in the States. So every country

has got its own national market and its own regional markets inside and

when you multiply that by ten, plus you look at a climate, which is helped

by public money, there is just a lot more opportunities to perform new

music that has no commercial value. There is quite a few of us over here

that are living as improvising musicians, that is to say that we can have

a family and a home and keep warm and healthy and earn enough money to

live that way. Nobody is getting rich. That's for sure, but you can figure

out how to do this to exist. I eat a good dinner every night.

FJ:

Joe Maneri, whom you collaborated with on an impressive ECM title, Tales

of Rohnlief, made reference that he is practically a ghost in the States,

yet when he travels to superstar, he is given a hero's welcome. Is it

just because as a culture, we are immature? After all, it wasn't so long

ago we celebrated our bi-centennial.

BARRE

PHILLIPS: No, I don't think it has got to do with that. I think today,

things are changing so much in society that these cultural background

things are getting erased very quickly and everybody is getting pretty

much on the same footing. I think the big difference is the structures.

Historically in America, contemporary art has to be a produce for it to

exist. Now, when you look at it on the music scene and they take contemporary

classical music, how many contemporary composers are there that lives

from their compositions in the United States? There is John Adams. Almost

everyone that I know in the States has a teaching job. I'm not against

teaching jobs. Don't get me wrong, but the teaching job, is it there to

keep you alive or is it there because you really want to be a teacher

and play a little bit or would you really want to play all the time but

you have to teach? These questions that are out there, whereas, here in

Europe, it is possible to live another way, to take the risk and go all

the way and figure out how to keep a low enough economic profile that

you can live with what is there, which is impossible to do in the States

now. I mean to have a normal life. Young guys can still do it, get by

and do their thing, but by the time they're thirty, they're burned out.

They just can't make it anymore. I'm just doing it. I've been doing it

since I was twenty-five. I've been doing it for over forty years. So there

is that and there is the infrastructure. There are all these institutional

or partially institutional venues to play in, that do programming and

have budgets to pay people. For this music (Tales of Rohnlief), we go

out with Joe Maneri, Joe and Mat (Mat Maneri) and I did a tour last June

in the States and half of the time, you are playing for the door and the

other half of the time, the fee is so low that they can't afford to pay

for your hotel or your transportation. It is a real problem of how can

you even go out and give this music to the public and not earn any money.

How can you do it without investing in it?

FJ: It never ceases to puzzle me how you can ask an important artist to

play for the door.

BARRE

PHILLIPS: Yeah, but who is going to pay for it if it is not for the door?

Most of the people who are putting the energy to organize these events,

find a place to do it, even if it is in their own house, put out the communications,

the little bit of investment, or if you want to do a good job, advertising,

do all that work for the newspapers and the radios so there is a place,

there is a concert, there are people coming and people can't play more

than ten bucks. That is already asking a lot. Ten bucks head for fifty

people, I am sorry, Fred, that is not going to get it. That will maybe

take care of one musician and the organizer, not at all. Sure, there are

exceptions. There are festivals that go on where they get it together.

But it is the everyday bottom line stuff that is really hard and really

separates the men from the boys. It is the same thing with recording.

With recording in the States, you either make it big or you don't make

it. You either sell a lot or you are out. There isn't any ECM in the United

States of being able to do something of whether you like the music or

not. What Manfred has done is incredible.

FJ:

It would surprise many of his recent followers, but Bob James was actually

an improviser at one time, and you were the bassist on record for that

ESP date, Explosions.

BARRE

PHILLIPS: That's right. It was very interesting. He was a wonderful jazz

piano player. He probably still is. I haven't seen Bob in years! I would

love to see this guy after all these years. He was accompanying Sarah

Vaughan at the time. He had the gig as the pianist in Sarah Vaughan's

Trio when we record that. But he was from Ann Arbor, Michigan and the

University of Michigan and hanging out in the music department at that

time were the likes of Robert Ashley, who was a young electronic guy in

the very early Sixties. He was very interested by all that. I don't remember

exactly how we met in New York, but we met and got along and we had this

same background of jazz and contemporary music and classical music, which

drew a parallel to our lives and he put it together to do this record,

to do the recording and so we did it in one day. Actually, when we had

to mix that record and master it, he was on the road with Sarah Vaughan

and I did the mix and master. It was the first time ever that I did that

kind of stuff, to mix a record.

FJ:

Let's touch on your latest for the ECM label, a recording with Paul Bley

and Evan Parker, Sankt Gerold.

BARRE

PHILLIPS: I've been playing on and off with Evan Parker since 1967. Paul,

I met in New York and played with him for a couple of months in 1962.

And then through the years until today, it is on and off. Sometimes he

calls me and sometimes I call him and we do a little tour together or

just the one off gig and so we've known each other for years and years

and with Evan, it is the same thing, but they had never played together.

They had never even met. I was the middleman, which is a good role for

the bass player. The project was put together by ECM, by Steve Lake. He

is a producer for ECM. It was Steve Lake's idea and Steve, knowing very

well that I knew quite well and had played with both guys so at least

there is somebody that they know and had the imagination of what that

combination of musicians could do, which for my money, we did. I think

those are beautiful records.

FJ:

As a bassist, what do a Paul Bley and Evan Parker bring to the table?

BARRE

PHILLIPS: Enormous lyricism and melodic content, harmonic propositions,

lots of human warmth and a really, a lot of great musical experience,

in terms of building music together. It is very pleasurable because they

are such great musicians and improvisers. All that music is all improvised

music. They are such great improvisers that hey, we can just go anywhere

and do anything.

FJ:

And so it never gets old?

BARRE

PHILLIPS: Oh, no, I've got so much work to do that I better be excited

or I am in trouble.

Fred

Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and celebrates the 5th of May. Email

Him.