A

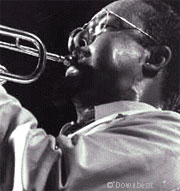

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH LESTER BOWIE

The following is an interview I treasure. It was a one on one that took

place almost two years ago and when I close my eyes, it still lingers

in the still of the night like it was yesterday. Hard-line traditionalists

frowned on Lester Bowie (even though, in his death, they can't seem to

get on the Bowie bandwagon quick enough). He didn't neatly fit into any

cute categories and he was as anti-establishment as one will find these

days. After all, Bowie was a card carrying member of the AACM, making

him one of only a handful or musicians who were doing anything creative

in modern music. It is too bad that working class musicians, like Bowie,

are slowly being eliminated all together from jazz, but isn't that in

line with contemporary society? Has anyone not seen the decline of the

middle class in America? I had an opportunity to sit down with Bowie and

he let loose on the current state of jazz, his new album, and his beginnings

as a young man in St. Louis. I am honored to have been one of the last

persons that Bowie spoke with before his passing and would graciously

like to give my thanks to his family, his friends, his record company

and his fans. I would hope upon reading this conversation with one a true

artist, you too will be inspired. Well, I hope and hope is all we have

and I cling to it daily. This is his portrait, unedited and in his own

words.

FRED

JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

LESTER

BOWIE: My father was a music teacher and he was a high school band director

in St. Louis for thirty years, and then he also played trumpet. So quite

naturally, all of us learned how to play music from the very beginning.

I think I started when I was about five years old and I've been playing

ever since. I turned professional when I was fifteen, started doing gigs

with people like Sonny Boy Williamson and Chuck Berry and then I just

went on from there, a lot of rhythm and blues people and eventually jazz.

I always wanted to be a jazz musician, but it wasn't always possible to

make a living playing jazz. So I got a lot of experience from the circuses

and carnivals and various rock and roll and rhythm and blues acts, The

Impressions. I was the music director for Fontella Bass, Jackie Wilson,

Albert King, Oliver Sain, Little Milton, Rufus Thomas, Carla Thomas, Jerry

Butler, Gene Chandler, just a whole host of all people that were on the

rhythm and blues scene in the early Sixties.

FJ:

What was it about the music that you wanted to make this your life's endeavor?

LESTER

BOWIE: When I was coming up in the early Forties, Louis Armstrong was

very popular and some of the records we had around was of Louis Armstrong.

And at that time, jazz was the supreme music. It was the pop music of

that time. Rhythm and blues was just beginning to, sort of, take hold.

Louis Jordan and cats like that, in the late Forties and early Fifties,

they started to take hold, but during that time jazz music was considered

the star and I wanted to be a trumpet player like Louis Armstrong. Clyde

McCoy was another one of my favorites. We also had a couple of Clyde records

and at that time he had a hit called "The Sugar Blues." The lifestyle

attracted me. My father was a trumpet player and a music teacher and I

don't even remember actually when I started. And I've never played anything

else. I tried other instruments, bass and fiddled around with the piano,

but I've never really attempted to play anything but trumpet. It was my

favorite, then and now.

FJ:

Influences?

LESTER

BOWIE: When I was coming up, St. Louis was quite a jazz town and there

was a lot of musicians around and I, kind of, followed them around. I

listened to a lot of records, of course, Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie

also helped me. I'd like to point out, Fred, that usually musicians have

two sources of influence. You have the musicians that you have heard about.

You've listened to their music and their styles influence you and then

you have the musicians that you actually hung out with, actually, that

really did help you. I always admired Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie

and even though I knew them briefly, I never knew them that well. Johnny

Coles and Marcus Belgrave were two people that we actually ran together.

They really gave me pointers, so I think they were really influential

in my selection of this music and the trumpet.

FJ:

Let's talk about your association with the AACM.

LESTER

BOWIE: Once we got together, I knew I was home. For example, I was working

as Fontella's director and we (Roscoe Mitchell) were doing a lot of shows.

We were traveling around a lot, doing a lot of shows. We finally ended

up moving to Chicago. After about a year in Chicago, doing jingles and

playing with various bands in Chicago, I was getting, kind of, bored,

because there was really no challenge to the music. And then there was

a baritone player that took me to an AACM (Association for the Advancement

of Creative Music) rehearsal and this was where I met the whole AACM.

Muhal Richard Abrams' Experimental Band (Eddie Harris, Roscoe Mitchell,

Donald Garrett, and Victor Sproles) was rehearsing and Roscoe and Muhal

and all the AACM members were there, Malachi Favors, they were all there.

Once I went in that room, I immediately knew that I was home. I had never

seen so many crazy individuals in one space. I felt immediately, immediately

I felt at home. By the time I got home from the rehearsal, Roscoe was

calling me on the phone and wanted to start a band and we started rehearsing

the next day and we've been playing together ever since. It's been about

thirty-three, thirty-four years now.

FJ:

Let's touch on your involvement with your Brass Fantasy Band, From the

Root to the Source, and The Art Ensemble of Chicago.

LESTER

BOWIE: All of those three bands almost compromise my total musical personality.

It takes that many different groups to really satisfy my musical curiosity,

so to speak. The Art Ensemble is the oldest band. We've been together

for thirty-three years now. The Art Ensemble is just an art group. It's

experimental and searching and trying to extend the boundaries of the

music, of the techniques, the compositions, the whole thing. We're really

searching, still are searching for a lot of newer things. Brass Fantasy

is what I call my avant-pop band. It's a show band. Instead of my normal,

white lab jacket, I wear a white, sequin lab jacket with Brass Fantasy,

because it's a show band. What we try to do is to play popular music,

but in a creative manner and in a way that people have never really heard

if before. It's about reinventing it. It's about taking a sound that was

made popular by singers that sing it and making that same emotional feeling

felt without have a singer, or guitar, or a bass, or keyboards. It's about

extending the language of the brass choir into the popular arena. The

Root to the Source was a combination of gospel, jazz, and rhythm and blues,

a combination of all the three. We have the rhythm and blues, Fontella

Bass singing. We had Martha Bass, who has recently passed, who was a gospel

singer. I had a, kind of, standard jazz quintet in the band and it was,

kind of, a combination of all those elements. We had the show elements.

We had the rhythm and blues elements. We had the gospel elements, I mean

that really focused on those areas and it takes those three to really

express myself. I couldn't really express myself in any one way, or with

any one group, or playing one particular sort of style. I think the musicians

of today are much broader in scope then they were, let's say thirty or

forty years ago. We draw influences from many places. We have much more

information, just as the people have much more information. The audience

now is very different form the audience in the 1950s. The 1950s were,

even before that, when Charlie Parker and Miles Davis did their thing,

when Duke Ellington was popular and Louis was popular. Louis was popular,

damn near, before flight. Planes were made out of fabric, so the times

have changed. People have more information now. People have computers.

People are on-line. The audience now will go to a jazz concert one day,

the ballet the next day, the opera the day after that, and then a blues

concert the day after that. They are much more informed and it takes much

more music to really impress them or give them information they don't

have and that's what I've been concerned with.

FJ:

The majority of the mainstream media is traditional and the audience,

as you perceive, is hungry for new knowledge. Does the mainstream media

impede on jazz's progression into the twenty-first century?

LESTER

BOWIE: Boy, Fred, it really does. It really impedes on it because what

happens is people, they believe what they read and they (critics), instead

of pushing to expand the horizons of the music, most of the critics have

been very conservative about, conservative that I must say, in a very

incorrect way. It's been a complete misinterpretation of what the tradition

of jazz is. You have this group of people that are traditionalists and

they call themselves in the jazz tradition and yet, they forget that the

jazz tradition is creativity. It's innovation. It's moving forward. It's

a young music that's growing and to impede the growth of that, to stunt

the growth of that, to me, is a crime. And that's what has happened. The

writers have really stunted the growth of the music. The music now, if

it wasn't for the few musicians that continue to push forward, there wouldn't

even be any music. The music would have stopped. It would be dead, just

like classical music has been killed off.

FJ:

There are very few living classical composers that are receiving any notoriety,

if fact, you could probably count them on one hand. Most of what is being

released was composed hundreds of years ago. If this trend in jazz of

playing what was already played, and played well fifty years before continues,

isn't jazz doomed to the same failures of modern classical music?

LESTER

BOWIE: You are right, Fred. They are trying to do the same thing with

the music. You see, Fred, once the culture is under control, if we control

all the art in this country, we can control the people. Music, classical

music is about stimulating the intellect. Art is about stimulating the

intellect, but once it's controlled and killed off like that, they call

it canonization and I call it blowing it up with a cannon. Instead of

developing the music, they stop the music in its tracks. That has happened

now. Lincoln Center is supposed to be the most important thing to happened

to jazz. Nothing has happened at Lincoln Center. Nothing has been created

there. There are no great musicians coming out of there. Wynton Marsalis

is supposed to be the king of the trumpet. This is the first time a leader

has been elected by someone other than the musicians themselves. It is

a shame because that is the attempt, to do exactly the same thing they've

done with classical music and with everything else. It happens also in

painting. The creative painters don't get a break. It's hard for them

to get out of here. It's really very difficult and that is a problem.

FJ:

Who are some musicians that are moving the music forward?

LESTER

BOWIE: The most organized of all these musicians has been the AACM, which

was an organization that was dedicated to moving the music forward. Muhal

Richard Abrams, with his Experimental Orchestra, Henry Threadgill, Anthony

Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, Leo Smith (Wadada Leo Smith), Leroy Jenkins,

there are countless number of members within that group that are trying

to move the music forward. And then your have, for example, we were inspired

by Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor, who are also still struggling very

hard to survive in this music after all of these years. You've got a countless

number of other musicians. You have some musicians in Detroit and in St.

Louis, Oliver Lake, the World Saxophone Quartet, the late Julius Hemphill,

all these are musicians that were writing in an entirely different way,

but whose work has almost been buried or stymied. I mean, we survive because

of our belief in the spirit of the music, but it's been very difficult

and I'm afraid that after we're gone, I don't know what's going to happen

with this music. Unless there is a group of people, and I don't see it

in the younger musicians, because as you said, Fred, they've been, sort

of, scared off. I don't see a movement of twenty, twenty-five-year-old,

thirty-year-old musicians towards playing creative music. I just don't

see that. The musicians that are creative are William Parker, oh, and

there's a drummer named Leon Parker, who is a younger musician. I really

like his work. He has a different approach to drums. And there's Olu Dara,

who is a guy my age that's been out there along time. There another, Graham

Haynes, who is a young trumpet player that's trying to do things. But

these guys are having a very, very hard time. I would imagine, a worse

time than we have had. It's an effort to kill the music. I hope for the

sake of this society that doesn't happen because jazz is the first music

that was representative of the whole planet, of all the people on the

planet. It was the first music that could accept influences from anywhere

and it's the only music that is in a growth period. All the other music

has been killed off. African music has been that way forever, Chinese

music or Indian music, but jazz is growing. It's going through all these

different things. It's still growing but, like I said, they're trying

to stop the development of it.

FJ:

You mentioned a few names, Oliver Lake, who had to form his own label

to put out his music, and Cecil Taylor, his recording output has diminished

drastically, what happens when these musicians, these standard bearers

fall?

LESTER

BOWIE: Well, I would hope that there would be someone, some guy, somewhere

that would continue this work. It doesn't take but a few. Hopefully, there

will be a small number of musicians that will continue this work. But

the problem is, will they be heard? This number is going to continue to

get smaller and smaller, where as, there may be fifty people now that

were involved when I was coming up. It may go down to ten after we're

gone. After that, I just don't know. I would hope that the music would

survive. I believe that it will survive, but will it survive, will the

society, of which this art is designed to enhance or to help develop,

will it benefit from the music? I have doubts about that. And then what

happens is, everyone just goes to sleep. We're much easier to control

if we don't think. Americans have been known through the world over as

a country that doesn't want the populous to think to much. Don't think

about this. Do what we tell you to do. I think it will just get much worse.

FJ:

This country is young and it still has a lot of growing up to do.

LESTER

BOWIE: Yes, it does. A lot more, not just a bit.

FJ:

Are these growing pains or a conscience effort by those in power to suppress

the music?

LESTER

BOWIE: Well, I do definitely see that it is a conscience effort to, by

media, by the leaders, the people in power. There is definitely, without

a doubt, a conscience effort to suppress this music. Hopefully, we will

get past this. Hopefully, one day the people will hear what we're doing

and once we can get, if we can just crack that door and get a foot in,

there's a lot that we can make available. I think we can really change

things, if we are just heard. For example, the Brass Fantasy, is a group

that's been together, I've had that group for eighteen years. Most people

are just becoming aware of that group, but that group has been surviving

for eighteen years. Here's a group that once you've heard it, you almost

fall in love with it and it opens the door for a lot of other things.

Hopefully, through the work we're doing and for the next few years, we

are trying to make sure that this music is available to the masses. If

it happens, I'm sure that things will change. People will, once people

hear a new sound, and people want to hear it. It's not that the populace

doesn't want to hear it, it's just that the people in between us and the

people that don't want to get his music heard. The people are ready to

hear something. They're hungry for it. I see it everyday. I see it in

their faces when they hear us play music that they haven't heard before.

It will survive. I don't believe that it's going anywhere. If we can ever

get through, one thing about our generation of music is none of it has

ever cracked through this barrier. No one has any power. None of us have

any backing. None of us are getting grants or anything like that. We're

not getting any sort of funding. We're not even getting support. We're

not even getting heard in this country. I worked in the U.S. once or twice

last year. Most of the work is done in Europe and in Japan and in Australia,

every place else but here, where the music was born.

FJ:

More reasons for me to bury my head in the sand.

LESTER

BOWIE: It's like what we were saying about this being a very young society.

The Europeans know that they benefit from art. They use art to stimulate

their young. A concert in Germany is half full of people under the age

of twenty, maybe even a tenth of those are under twelve. The rest are

of all ages. This (America) is a young society that doesn't realize the

importance or the connection between the art and the intellect. The older

societies realize that. They realize there is something to learn in this

music, there's something they can teach their young. They've got some

jazz schools in Europe, and Germany, and Italy, and they've got some musicians

in Italy and France that are just unbelievable because they have been

learning from these musicians that have been shunned in the States. So

they understand that. They've gone past what we're into now and they realize

that any new art form, regardless of where it comes from is of importance

and will aid in the stimulation of their intellect, and thus enhance their

society. They realize that. We, here, haven't gotten into that yet.

FJ:

Using the recent example of the American media's fixation on the happenings

in the Oval Office and how Americans perceive something such as sex so

differently than Europeans, is this society breeding a society of fear?

LESTER

BOWIE: People are afraid to expand their intellect. Their mind is not

familiar. It seems as though the American power structure is intent on

keeping us unthinking, that way we will just be consumers, and service,

and employees. It's like we don't understand that people need to think

to develop this society. They think that they know. They think that they've

got a safe percent of people in this country that know which way we should

go and they want to go that way. They don't want to take a chance on anything

else happening. What it does is it narrows the scope of thoughts of the

people here and it just keeps us more uninformed, which is really a drag

because like you said, Fred, every place else in the world, what's going

on with Clinton is a joke. I mean, it is a complete joke. Americans are

always considered jokesters anyway. We were always jokes. I used to sit

up in this café in Paris and the Americans will walk by and you see the

French giggling, "Here comes some Americans." And they laugh. "Those Americans,

they don't even know how important jazz is." That is happening because

the lack of knowledge of their own music. Just to give you're a quick

story, Fred, I was coming back from Italy on a plane. On one side of me

was this woman with two Ph.D.s and the other side of me was this guy who

was an old Italian baker. So I got to talking with the lady with the Ph.D.s

and I was telling her the same problem and how we are just so uninformed

and how we know nothing about the music. I said, "For instance, you, with

all your degrees has no idea of the culture of America. You knew nothing

about jazz." She goes, "Well, I really don't know anything about it."

I said, "Now watch this. Neither one of us knows this guy. Let me ask

this guy next to us, old, Italian guy, what he knows about jazz." I just

mentioned jazz and this guy started naming records and naming people.

He knew all about it. He was telling me about all the records he had.

He was coming to the States to visit one of kids, but he was just a random

European that knew more about American music than an educated, intellectual

American, and it just really embarrassed her and it also illustrated what

we're talking about now.

FJ: Let's talk about your new Brass Fantasy album on Atlantic Records,

The Odyssey of Funk & Popular Music - Volume 1. Why improvise on a Spice

Girls tune?

LESTER

BOWIE: You see, Fred, I've got four daughters (laughing). What we were

trying to do with that particular record and with that group, the Brass

Fantasy, is to play music that is familiar, but in a completely creative

manner, in the way it's written and in the way it's presented. The Spice

Girls' song, "Two Become One" is really good song for flugelhorn and brass.

It's in a low key and it's kind of mellow and its really a good song.

That's the main reason that I picked that tune. It really worked perfect

for the band. At the same time, it was within the idea of what we were

trying to do. We were trying to show, like the record says, it's the odyssey

of funk and popular music and what a creative approach can do to this

music. I've played these tunes for kids, and these kids go crazy. They've

never heard a song that they knew, played by a bunch of old men with horns

(laughing). It just knocks them out! I tell you, Fred, I've played at

elementary schools and some high schools, and it's unbelievable what happens

when people actually hear this music. We're trying to show kids that we

appreciate what they're doing. We appreciate the songs that they appreciate

too, but here's what we can add to it. This is what can happen when you

utilize a creative approach. It can be this way. This song can be a million

different ways. That was one of the traditions of jazz. That's one of

the things that made jazz popular. Miles Davis got popular by playing

songs from Oklahoma, you know, "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," "Bye,

Bye Blackbird," "When I Fall in Love." All these were show tunes and this

is what enabled him to reach out saying, "Please somebody, please hear

this music. Hear what the possibilities are." And once you hear the possibilities,

we can open this whole new world of creative music.

FJ:

Is that what jazz is to Lester Bowie?

LESTER

BOWIE: Jazz is really a creative music. I think it is the best way to

really describe what it is. It's a very creative and innovative music,

with the emphasis on creativity, creative compositions, creative instrumentation,

creative approaches to the music. I think it's very important that we

listen to this because being creative and innovative is very important

to our lives, very important.

FJ:

Sounds like a musical goal?

LESTER

BOWIE: I'm trying to be creative, but I have a very broad scope, a very

broad idea of what the possibilities are for this music. The main thing

is to be creative, to be innovative.

FJ:

I don't think many traditionalists and critics have a clue who Notorious

B-I-G is.

LESTER

BOWIE: I know it (laughing). I know that they're going to be upset with

me, but I don't care. It's OK. They can be upset. What we're trying to

do is to show that there is so much separation in the music and jazz is

the music that brings everything together. It brings all the people together.

I was talking to some group about racism and I said, "One thing that I've

noticed is we don't have that in jazz." Jazz fans seem to be cool. Somehow,

the music has elevated them above that. The music can elevate us above

a lot of things if we just let it. And that's what we're trying to do,

elevate the people.

FJ:

And the future?

LESTER

BOWIE: Hopefully, this record will get heard and if it gets heard here

in the States, you can expect a lot from me. I've got so many projects

in mind. The problem is, we all are getting much older. I am a sixty-year-old,

almost sixty-year-old grandfather. I've got eight grandkids and two more

grandkids on the way. I'm going to have ten grandkids in the next few

months, and so I hope people will pick up on this quickly while we'll

still around. If they do, we can show them things in music and combinations

of music that they haven't even heard yet. For example, in the States,

they've never heard the Art Ensemble's tribute to Chicago blues. We did

a tour of that. They've never heard the Brass Fantasy. I did a brass /

steel tour, which is the Brass Fantasy with a world champion steel band.

We've done projects that no one here even knows about. If we can get through,

if we can get enough attention, we can start to make these things available

here. We can make them available. If we can get the people to hear the

music, I'm sure there will be no more problems. The problem is only in

getting heard. Like you said, Fred, you go to Yoshi's (San Francisco)

and there's a line around the block. That's because we've been going out

there and they've heard the music. They know what to expect. They know

it's going to be exciting. There used to be a time that you go to a jazz

concert and you were excited about the musicianship, excited by the music

that they were playing, excited by the way they looked. We want to bring

all of that back.

Fred

Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and the guy behind the guy. Comments?

Email

Fred.