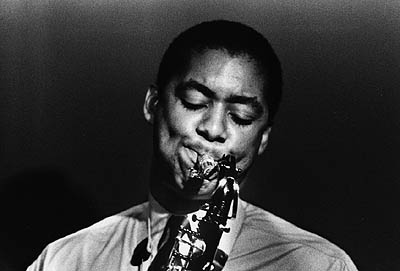

Courtesy of Branford Marsalis

Columbia Records

Sony Classical

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH BRANFORD MARSALIS

Not to stroke my already huge ego or increase the size of my head to the

point where it hinders the rest of my body from getting into my affordable

luxury, Asian sedan, I have an impressive number of interviews under my

belt. Some were better than others, but those I treasure are the ones

that don't sound scripted. I have been jonesing to speak with Branford

and his younger brother Wynton for as long as I can remember, not because

they are celebrities, because they both are, and certainly not because

of their musical skills, because both have plenty to spare, but more because

I wanted to get the facts straight for myself in a effort to make the

music more accessible to me. Wynton has one too many publicists and a

writer needs to make one too many phone calls (which I am too pretentious

to make) to get to Wynton. Branford has one hectic schedule and it was

stretched even thinner with the birth of his newborn son not five weeks

before we were scheduled to sit down. To my surprise, Branford (son in

his arms) did not stand me up, but rather was gracious enough to call

me on a Saturday from his home upstate for what turned out to be a no

holds barred one on one, as always unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: It was challenging.

FJ: What is so challenging about jazz?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: You have to listen to it to know. It is sort of like

trying to explain what's intellectually challenging about physics. If

you try it for ten minutes, you'll know. (Laughing) There is no other

way to really explain it. But I grew up listening to R&B and rock

n' roll and as an instrumentalist, meaning a saxophone player, I mean,

I am not a good singer. I can't sing for shit. I just felt that there

were other things out there that could occupy my brain, that could challenge

me intellectually.

FJ: Was the saxophone an intellectual challenge?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: No, it was just a way to get chicks. Yeah, I was playing

clarinet and you ain't going to get nowhere with the clarinet.

FJ: Did you end up getting play?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: No, not at all. But it was still the idea that I could

play in the jazz band and I could join a rock band. Have you heard any

clarinet solos in rock music? Except for Sting's last record when he had

me do that shit, but other than that, it doesn't work. The saxophone was

a way for me to join bands. I was in a band, but I was playing piano and

I just wanted to get the hell off of the keyboard. Lugging a Fender Rhodes

around at the age of eleven is not a cool gig. It is not a cool gig.

FJ: Having done a stint in Art Blakey's band, what did he impart to you,

both as a man and as a musician?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: As a man, I learned a lot about how not to behave.

He was a bad boy (laughing). He was, Fred. It was great. He only, he never

told you what to play. He always told you what not to play and it really

helped me as a bandleader. He would tell me stories that seemed completely

absurd. For instance, if I was playing a bunch of things that were technically

impressive, yet not really germane to the music, what Shakespeare would

call "noise in dumb shows." I mean, you can play a solo and

play five notes over and over again for thirty seconds and people will

applaud. But if I would do some shit like that, Art would turn around

and say, "Hey, man, why does a dog lick his balls?" You know

that joke, Fred?

FJ: Because he can.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Exactly. In other words, what was the musical reason

for what you played other than the fact that you could play it? Now the

first time he did that to me, I was like, "What the hell does that

have to do with what I've just played?" But the joke sinks in after

a while. It was like those little things really made a difference. It

is one of the reasons why when I play ballads I don't play cadenzas because

Art kind of cooled me out on that. It all makes sense. Other than to display

technical virtuosity to amp up the people who didn't have enough hipness

to understand the point of the ballad, there is no reason.

FJ: So grandstanding isn't cool?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Not really, no.

FJ: While playing with your brother Wynton's quintet during the early

Eighties, the group drew numerous comparisons to Miles' group with Wayne

Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. That is a lot

of weight to place on the shoulders of a handful of twenty-year-olds.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: First of all, my father is a musician and an academician.

So we already realized that we spoke English better than most of the people

who were writing those articles, so they didn't bother us. We could write

better than they could and we knew more about music than they did. But

at the age of twenty-one, the only thing we were thinking about is getting

laid, Fred.

FJ: Did you get some play then?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Yeah, we did all right then. But the whole point was

that we were still twenty-one and that is the point that gets lost in

all this urban legend shit, all the myth of that band and the whole thing

is that we were sitting around. Wynton was a lot more studious than we

were. We was just out there bullshittin' and drinking and hanging out

and having a good time. It was just we were doing it in a fashion that

was a hell of a lot more challenging musically than more of my compadres.

Where as, sometimes in a pop setting, in a rap music setting, the beer

is an essential accoutrement to the gig. You are on stage drinking it.

That's the whole point. There is a social aspect to the shit that draws

people to it.

FJ: That group set in motion the fixation that was the "young lion

movement." There were veterans that couldn't buy a record deal or

get a blurb in a magazine and that group was treated with kid gloves.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: I think that Wynton and his band were responsible for

the next generation of jazz musicians even existing. So there are a whole

bunch of teenage kids who suddenly wanted to play jazz that didn't want

to play it three years ago or even one year earlier. You see these young

kids in suits and you say, "Hey, that could be me." So there's

all these people who talk about that band. They were there and they heard

us do this and they heard us do that. They weren't fucking there, Fred

(laughing). And the fact that Wynton has gone onto be successful and I've

gone onto be successful and Kenny Kirkland was successful and "Tain"

was great and Bob Hurst was great, it just takes on a life of its own,

Fred. It becomes some other kind of thing.

FJ: Since I am a handful of years your junior, I have been privileged

to witness your development as a player firsthand, from the first record

of yours I purchased, Renaissance, on through to Trio Jeepy, The Beautyful

Ones Are Not Yet Born, and your latest sessions, Dark Keys, Requiem, and

Contemporary Jazz.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Thank you, Fred, but it was a work in progress up until

the last three or four.

FJ: The virtues of humility. But reflecting back on your earlier recordings,

critics have maligned you for trying to sound like Coltrane or Wayne Shorter.

Was there a particular sound you were going for?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: It is not really humility. It's arrogance actually.

Arrogance doesn't really get its proper due. What passes for arrogance

in pop culture is basically insecurity. People who give a fuck about what

color the M&Ms are in the dressing room are considered arrogant, when

they are just ignorant. It was my arrogance that wanted me to be a great

musician and my arrogance allowed me to do whatever had to be done, no

matter how humiliating it was because it wasn't really humiliating for

me in the long run. It was short term misery for long term gain. When

I was playing with Wynton's band, I was trying to sound like Wayne Shorter.

When I wasn't in Wynton's band, I tried to play like John Coltrane and

Sonny Rollins and Charlie Parker. And then it was Ornette Coleman. On

different records, it was different guys. On the trio record, it was more

like Ben Webster on certain songs. I mean, you just keep going and try

to learn things and add to the repertoire. I wasn't really interested

in playing the pop culture game. And the pop culture game is the notion

that when you read criticisms that you're twenty-three years old and he

doesn't have his own sound, but if you really studied the music, no twenty-three-year-old,

save the few geniuses, had their own sound. It is one of those things

that comes after a period of serious apprenticeship. Being well aware

of that and having that philosophy fortified by peers and my elders, asking

Herbie Hancock and Miles and Ron Carter and Elvin Jones and Art Blakey

and having them pretty much say, "Yeah, that's the way to do it."

Shit, my mind was made up.

FJ: You know a thing or two about pop culture having toured with Sting.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Yeah, I loved it. I wished that I could have been a

little older when I did it. I just would have enjoyed it better. I would

have enjoyed it differently. When you are twenty-one or twenty-three,

you think of shit that's happening to you as though it is supposed to

happen to you. You don't really think of how hip it was. You're just living

in the moment. You live in the moment. Playing in front of ninety thousand

people is awesome, but I was also twenty-one so I was like, "Yeah,

but what do you expect?" And you got the pressure from all sides

because you had people who dug jazz saying that you had sold jazz out

and then you had no idea what jazz was saying that shit that we were doing

with Sting was jazz. So it puts you in a strange place because I had no

intention of defending my choice to go with Sting like some of my predecessors

did when they decided not to play jazz anymore. They felt like they had

to defend themselves. "Well, we're trying to bring the music to the

masses," and they said all this shit in the Seventies, which was

stupid. And I was like, "Fuck you guys. I do what I want to do. Don't

tell me what to do." But then on the other hand, you have all these

people all of the sudden saying, "It's great that you're bringing

jazz into the twenty-first century, twentieth century" and I was

like, "Wait a minute. This shit is not the answer for jazz in the

twentieth century." I should have just went, "Yeah, yeah, thank

you." I should have ignored those guys because they weren't really

interested in an earnest discourse on the subject. They just wanted to

have something catchy to say and I should have just let them say it.

FJ: I know he gave it a good college try on Joe Henderson's Porgy &

Bess record, but is Sting hip to jazz?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Yeah, and he has the intellectual capacity to get to

it too. I mean, he's not Mr. Jazz, but he's been exposed to it and he

can come to one of the concerts and he could get something out of it and

enjoy it and that's all you can ask from anybody that doesn't play it.

FJ: Although you had a stellar quartet with Kenny Kirkland, Bob Hurst,

and Jeff "Tain" Watts, as on Trio Jeepy, you like going pianoless.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Yeah, I loved it. I loved it, Fred. It started out

of necessity because Kenny was working on his own project and quite honestly,

Fred, we couldn't find any musicians who had modern touch. Most of the

guys were still beboppers and post boppers and they didn't really work

well with our sound, so we went trio out of necessity. But after we started

to do a couple of gigs, I started to dig the possibilities of it, so we

ended up making two or three records that way.

FJ: My condolences for the passing of Kirkland.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Yeah, it was tough personally, not musically because

I knew Joey Calderazzo was going to step in and I knew that the way he

learned music was different than the way we had learned and there would

be this trial period. There was a tough time, not Requiem because Kenny

was alive then and so we were just making the music. A couple of the songs

that are on Contemporary Jazz, like the first tune, was actually supposed

to be on the Requiem record, but the first time I brought them the music,

he couldn't play it. Kenny couldn't play it well and "Tain"

couldn't play it and I just enjoyed that shit to no end. I'm like laughing

and Kenny said, "You like that shit don't you?" I said, "I

love it. Motherfucker when you die and when you die and I die, we'll be

in heaven and I will come see you and say, 'Remember that song that you

just fucked up on the session?'" And we had a laugh about it and

two months later, he was gone.

FJ: You revisit your affinity for classical music with your latest for

Sony Classical, Creation, fifteen years after your first classical recording.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: I'm interested in playing good music and challenging

myself and the distance just reflects the time in which I was doing a

whole bunch of other shit.

FJ: I am told it is a significant transition to go from improvisation

to reading score.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: No, it is the same mentality. Even though it is improvisation,

we have songs and there is specific parts that need to be played in jazz.

The hard part is to put yourself in the mindset, in a European mindset,

which is the thing that makes jazz so difficult for a lot of people to

play it even though it's a world music. What has become the world is the

outside of the music, the periphery of it, the notes and the chord changes,

and the fake books. But the real spirit of the music is really, really

difficult for people, and I say people, not just white people. It is difficult

for black people in America now to really get to the place where they

can embrace the soul of the Southern black man.

FJ: How can a black man not appreciate the troubles of a black man living

in the South?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: The South, they don't live in the South and if you

don't live someplace, then what you have to do is you have to have a severe

amount of empathy. If you watch a lot of movies, one of the things that

human beings lack in general is empathy and understanding. If you take

a movie like, that movie, I watch a lot of movies, remember that movie

John Travolta was in when like some part of his brain functioned differently

because he had a tumor? He could read books in a second.

FJ: Phenomenon.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: And remember all his friends turned on him and treated

him with suspicion. That's because they don't have empathy. Everybody

grows up believing that the world is flat, even though we know it's round

now. We grew up believing the world is flat. In other words, there are

things that human beings are supposed to do and then there are things

they can't do. When they can do some shit that's beyond normal, either

something's wrong with them or something's wrong with me. And people don't

like waking up believing that there is something wrong with them personally,

so it has to be the other guy. They don't think of the third option. There

is nothing wrong with anybody. It is just he's really good at that and

that's the way the shit is and unless we try to understand what he's going

through, then no. That's what I mean. You have to have a tremendous amount

of experience and empathy. For instance, when you listen to an old blues

man like Robert Johnson or one of those guys, you have to try to put yourself

in their mind and hear the music from their point of view rather than

just breaking it down into some barebones chords.

FJ: Is empathy even conceivable in this day of the internet and Direct

TV?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Yeah, but it's not really about that, more so than

it's about, you can do the same thing on the internet. You just have to

get a sense of something that's larger than what you're used to and that

is the thing that I had to do with classical music. I am a black child

from the South, certainly not the place where Beethoven was born. So what

I have to do is try to put myself in that mind. Through movies and seeing

movies of old Europe and reading Shakespeare plays and listening to classical

music, I can put myself, like I can listen to Beethoven and imagine that

I'm in Hamburg or Dusseldorf or Hanover in eighteen-something and I am

sitting there hearing his music. I can imagine the shit and once you can

start to do that, you start to have a certain level of understanding and

empathy. And I've been to Germany and that helped immensely. I understand

the German point of view. I've been to France because I'm sensitive to

it.

FJ: Did your empathy come with age?

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Oh, of course. But I also had a natural version of

it that I was always grateful for. When people open my eyes to something,

I didn't shut them out. I can tell you one story that I always remember.

We were playing at the University of North Carolina. We were invited to

this party in Chapel Hill and sitting down at seat was a very, very attractive

white woman, the only white person in the place. I sat down and talked

to her and she says, "I can't believe you're talking to me, the way

the people are looking at me, treating me bad. They don't even want me

here." My immediate response was, "No, you have that backwards.

You see, that is what white folks do to black people. We don't do that.

We are incapable of being racist. That's not our thing." She was

like, "Well, you're wrong. You see the way they're looking at me."

I looked around and said, "They ain't looking at you. You're paranoid.

Look, you want a drink?" She goes, "Yeah." "So I will

get you a drink and I will be right back." And it took a little long

to get the drink and when I came back, she was gone. And I don't remember

her name, but I said, "Where did such and such go?" The black

woman there said, "I don't know where she went, but I'm glad she's

gone. Who invited that bitch here anyway?" And all these chimes came

up, "Yeah, who invited her here?" And it took me aback. And

the thing that surprised me was not their response. What surprised me

was that I consider myself a forward thinking person. How could I not

have noticed that that's what was going on?

FJ: I guess we have moved past the colored only and white only signs and

into a more subtle version of hatred.

BRANFORD MARSALIS: Oh hell yeah, Fred, it has always been that subtle,

expect when you hang somebody from a tree. But other than that, it's subtle.

It's subtle now. It's like a subtle thing like if you turn on the television

and you watch shows, every black sitcom is all black and every white sitcom

is all white. Do you think that's a coincidence? I mean, sitcoms are supposed

to reflect a situation in American life. That pretty much tells the story

right there. Yeah, it's that subtle, but the thing that I learned from

it was that I thought I was a forward thinking, hip person and I was completely

blind and I vowed to myself that I would never be that blind again.

FJ: You've spoken of your affinity for film. People may not realize, but

you have made a number of appearances in various feature films.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Yeah, it was fun. It was fun. It was nice to do, but the audition

process is brutal and I don't like the idea of taking good jobs from real

actors. The whole system is set up so that it caters for to people (baby

crying in the background). Oh, oh, he's five weeks old.

FJ:

Congratulations.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: It caters more to people who are interested in, particularly

on the black side, it caters more to people who are interested in being

famous, rather than being a part of quality work. Like black people have,

since entertainment started, we've been America's comedians and not much

has changed. Virtually every successful black movie is a comedy. Not virtually,

every successful black movie is a comedy.

FJ:

Society still has that black face expectation.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Well, of course, expect the people who make the movies and the

people who watch the movies say that, for instance, it's not the same

because Chris Tucker is going to make twenty-five million dollars to make

his next movie, which is whatever that movie he did with Jackie Chan (Rush

Hour) part two. The money somehow makes it different. But the money is

the least of the issues for me. Yeah, sure, the money is great, but the

reality is that we're still playing the same roles we were playing eighty

years ago. It's just that we don't got to put on white lipstick on our

lips and black face on our faces.

FJ:

But you enjoy the comfort money brings?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Yeah, I put it to good use. I spend it all.

FJ:

Because you could have cashed in had you stuck around on the Tonight Show.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Yeah, well, you know. I like money, yeah, but money is not a

means to an end for me. I will never allow myself to be defined by how

much money I make, so given that fact, I'm not really a slave to it.

FJ:

You got a lot of shit for leaving the Tonight Show. I recall your appearances

on the Howard Stern Show and he would chastise your decision to part ways

with Leno.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Well, I can understand Howard's point of view because Howard

has to answer a question for himself that I had to answer. How much is

too much? How long should you stay? When you listen to Howard, he doesn't

sound particularly satisfied with his job in the last few years. How long

does a forty-five-year-old, forty-six-year-old man sit around and tell

chicks to take their clothes off before you start saying, "I've got

daughters at home. What the fuck am I doing?" That's worse than sports

because there is not an age limitation. In sports, you physically tired

out, you go. But in entertainment, I've got this thing I can do that really

makes me successful even though it is unfulfilling for me. What do I do?

It is a simple question for me. I like being fulfilled.

FJ:

Reviewing your discography, with your brand name, you could have recorded

a hell of a lot more than you have.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Well, I record when I have something to say. It's as many times

as I record. If I don't have shit to say, I'm not going to record (laughing).

If I don't have nothing to say, I'm not going to waste my time.

FJ:

Amongst your peers, there are musicians who record a record a year.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Yeah, well, I don't see how that helps them. It's not like they

have a record a year of interesting things to say. I think that, particularly

in jazz, they haven't really figured out any other way. The whole music

industry is now pop. When I do a record, I do interviews and people come

up to me and say, "So how long is your Contemporary Jazz tour going

to be?" The tour becomes the name of your last album. I'm like, "Well,

we don't tour that way. It's not the Contemporary Jazz tour. We're not

just going to play songs from our record. We're going to play whatever

we feel like playing at any given moment." "So how many cities

will you be playing," because that's what it always says, "The

Rolling Stones are going out on a six month, eighty-seven city tour."

We don't do that shit. We tour. We're kind of like Hootie & the Blowfish

are. We make records to go on tour. We don't tour to support our albums.

FJ:

Of the sporadic times you have recorded, there is enough material in the

Columbia catalog for a best of Branford Marsalis album. Would you support

the record company's decision to release such an album?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: It's their right. They can do whatever the hell they want. I'm

only interested in making music. If they think they can make money by

doing that, go for it. It's no sweat off my nut. As long as they don't

make it count against my contract, that's their decision. If they want

to do it, let them do it.

FJ:

You were anointed as Columbia's Artistic Director, but without completing

your tenure, you resigned the position, why?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Because it didn't mean anything. The Artistic Director can only

be as artistic as those that are above him allow him or her to be. And

I was not really interested in stealing a paycheck. I wanted to record

creative music and I wanted to have that creative music promoted in a

fashion that was acceptable for the largest record company in the world.

And if everybody who works for the company is more in tune with pop stars,

Mariah or Ricky or Wyclef or whoever it is, then we have no way to succeed.

I'm not naïve. I'm not saying we would sell a million records. We'd

be lucky to sell twenty-five thousand. But twenty-five thousand for a

jazz record is acceptable. Eight thousand on the largest record company

in the world is just not acceptable, so it didn't make any sense to make

promises to musicians that I could not keep.

FJ:

So yet again, you walked away from the money.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Well, you know, it's my reputation at stake.

FJ:

As you've grown in age, is that important to you now, your word?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Well, my actions speak for themselves I think.

FJ:

Does having the name Marsalis carry with it a certain level of expectation?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: No, it is just a name brand now. It's like Coca-Cola except

not as lucrative. They go, "Oh, there's the jazz guy." It's

not like they buy our records. They don't buy our records. It's just a

name they know. The difference is like when I go into a store like today

to buy a suitcase and I put my card down, the guy doesn't ask for ID or

he doesn't look on the back of the card to check the signature. He just

gives a wink and says, "Here you are sir. Have a nice day,"

and he smiles real good, so he recognized me. "I'm a huge fan of

your music." And all I've got to do to accept the pie is to say,

"Really? Which one do you like the most?" "I don't remember

the name." We used to do that shit with Wynton's band. Wynton used

to do it all the time. "I love your music." "Really? Which

one do you like the most?" "Uh, uh, uh, I don't remember the

name." Yeah, but if it was Stevie Wonder's record or anybody, you

would know the name wouldn't you? You have to accept that that's the reality

of it.

FJ:

Fatherhood suits you.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Yup, love it. It's kind of like jazz music. The payoff is down

the road. It's not like what do you love about it in this moment, but

now that my son is fifteen and I see him, he makes me proud, which also

makes me proud of myself because he could have gone either way. He could

have gone either way, particularly when you start having a certain level

of financial success and you move into the suburbs. You can put yourself

in a situation where, like I was with my wife and she had this In Style

magazine and there's all these people's pictures in there and I know all

the people and I looked up and said, "Wow, that could have been me."

I could be in In Style and at the parties, but the reality is that when

you have children, everyday you are at the parties is a day you are not

with your kids. And you go to enough parties, your kids end up raising

themselves and that's when the bullshit starts. That's when you have a

movie like Traffic. There is a part of the movie that if you really paid

attention to it, you can gain from it. If you pay attention, but if you're

not truly paying attention to the movie, because they didn't really dwell

with the parental guilt that he feels in neglecting his daughter all those

years when he was trying to be famous. So it is like every time I could

have been on the television show or every time I could have been in a

movie and it conflicted with my son's birthday or some game he wanted

to go to, he plays baseball, and when some little league game and I turned

it down, I see the way he's turned out and you say, "Yeah, this shit

was all worth it." Verses some of my friends who were like, "Why

don't you just hire a nanny? Why don't you let somebody take care of your

children?" That's not why I had children.

FJ:

What film gets your nod?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Magnolia because it's real. It is just real. It evokes real,

earnest emotions.

FJ:

Did you understand the symbolism behind the frogs?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: No, I don't think you have to. I don't think you have to understand

everything, like when she is buying all those drugs and the man starts

saying, "You're going to have quite a party aren't you?" And

she says, "Fucker, there is death in my house." Yeah, you get

that or when the old boy is old and dying, now he feels guilty and the

vulgarities of his life about molesting his daughter come popping up.

It's like why didn't the mother speak up sooner? She had to have thought

that shit ten years ago. To me, it's all these really human, personal

answers that people are so uncomfortable with. That's what I dig about

movies like that, The Scent of Green Papaya (L'Odeur de la Papaye Verte),

that's a great movie. It's a Vietnamese film. It's a film that basically

parallels the European-ization of well off Vietnamese and if that is the

best thing for them and is that the right thing for them or should they

all live like the peasant girl who finds joy in the scent of green papayas.

We were just looking at Xiu Xiu: The Sent-Down Girl, which is another

Chinese movie. That's a great film.

FJ:

You should rent Shanghai Triad.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: No, I didn't see that. Who is in it?

FJ:

It stars Gong Li.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Oh, the finest woman on the planet. All of her movies are great,

all those, you know, Farewell, My Concubine. So Shanghai Triad? I'll go

copy it at the store today.

FJ:

While you're there, rent The Emperor and the Assassin.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: I saw that. What I thought upon watching it was that it was

too Chinese for me to get. And what I know just from talking to people

in different countries, having never really been to China, is that there

are certain things that are part of unique national experience that cannot

be translated into another language and I thought that a lot of that was

about being Chinese and there is just certain shit you are not going to

get unless you spend enough time over there to get it.

FJ:

During the beginning of the interview, you alluded to the fact that you

were arrogant earlier in your life. Are you still arrogant?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: Oh, yeah. Hell yeah.

FJ:

So what wisdom have you gained in twenty years?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: I learned a lot. I learned a lot because I'm totally arrogant.

I think it is kind of like I am arrogant in the absolute English dictionary

sense of the word arrogant. I don't think that I'm better than people

on a human level, but I'm certainly a better musician than most people.

So if I'm sitting on a place and somebody wants to tell me about music

and they don't know music, I just don't want to hear what the fuck they

have to say. That makes me arrogant and I am arrogant that way, but I

don't have that kind of arrogance where a woman can pick up a stray dog

and damn near make love to it while stepping over a homeless man. I don't

have that kind of arrogance or like I just gloss over the shit that makes

me uncomfortable. I can't tell you how many times that I've rolled down

my window and told a homeless guy that I just don't have the change to

give you and his response is like thank you, for looking at me. "Thank

you, for treating me like a human being for fifteen seconds." So

that's what I mean. Am I arrogant that way? No. More people I know are

arrogant that way. They are afraid of homeless people. What in the hell

is a man who lives on the street going to do to you physically? He has

no stamina and no strength and probably drinks too much. What the fuck

is he going to do to you that you can't roll down your window and just

be kind for five seconds? But on the other hand, when it comes to music,

yeah. People come to me and say, "What do you think of Eminem?"

Yeah, I am completely arrogant to them.

FJ:

What do you think of Eminem?

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: I think Dr. Dre has some great beats. That's what I think. Everybody

is like, "Don't you think it's wrong that Eminem is pop record of

the year?" I say, "Not really." I think, having listened

to rap since it started, he certainly is not the first person to make

a rap record with cursing and misogyny or homophobic bullshit, certainly

not the first, not even close to being the first. And if you are going

to do that kind of shit, Public Enemy was far more witty about than he

was. So the question that I have is what is it that Mr. Mathers has that

makes radio stations that didn't play any rap at all, suddenly start his

records? What is it that he has that makes his record become one of the

first rap records of that kind, to suddenly be pop album of the year?

Is it that much better than Alan Iverson's record? Is it that much better

than Method Man's record or DMX's record? Is it that much better that

it can be pop album of the year? What is the one thing that he has that

they don't have?

FJ:

He's white.

BRANFORD

MARSALIS: That's a question that every person has to answer themselves

that voted for him. I'm just asking the question. I'm not sure what the

answer is. Maybe that's not the answer. Maybe the answer is not always

what you see, but then again, maybe the answer is exactly what you see.

So I'm saying, the whole controversy about Eminem. I'm looking at the

controversy from a much larger picture. One of the things I was talking

about with a guy just earlier was that the reality is that you can think

of my opinion like toilet paper. Anybody can take what I say and wipe

their ass with it. The thing that I don't understand is why people are

so uncomfortable with discourse. I have a friend of mine who used to be

President of Beloit College, which is a small college in Wisconsin. It's

a liberal arts college. And he did his own test and he found out that

even in the liberal arts colleges, the students were basically overwhelming

saying that they would be for apt to have a conversation with a person

when they could be assured of the outcome and if they found themselves

in a conversation where the conversation was going against what they thought

is should be, their first inclination is to terminate the conversation.

And that is just some sad shit. All I know in my dealings with people

is all people want me to do is agree with the shit they say. The moment

I say something that they don't agree with, they get mad. And I'm like,

"Instead of getting mad at me, why don't you explain to me why I'm

wrong?" And I'll give it a good listen. It kind of reminds of something

my grandmother used to say when she would catch me doing something and

I would get mad and deny it. She would say, "Son, if you threw a

brick in the crowd, the one that it hits will always holler." And,

Fred, there is a lot of hollering motherfuckers out there.

Fred

Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and does not believe the Russian Mafia can

hold a candle to the Italian one. Email

Him.