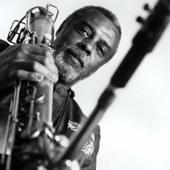

Hamiet Bluiett

A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH HAMIET BLUIETT

I can't imagine the baritone saxophone would have any prominence what

so ever if Hamiet Bluiett were not blowing the hell out it on every record

and in every performance. As one quarter of the World Saxophone Quartet,

Bluiett has his place among the jazz history books secured, but there

should be a whole chapter devoted to what he has done for the big horn.

The baritone and fans of it ought to send thank you notes to Bluiett each

and every day, because for my two cents, I would never listen to the baritone

as heavily as I do if it were not for men like Bluiett, Vinny Golia, and

James Carter. So I present, Mr. Hamiet Bluiett, unedited and in his own

words.

FRED

JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

HAMIET

BLUIETT: When I was younger, the music was always around me a lot, everywhere.

You didn't have MTV and all that kind of stuff. In fact, Fred, I am going

down before even television. There was music on the radio and music in

church. There was a lot of live music and music in the educational system.

There was just a lot of live music. You didn't have as much recordings

as you do now, so you had to search to find records and things of that

nature. You had them, but not like you do whereas everything now is on

CD. It wasn't that kind of situation.

FJ:

The advancement of technology allows a person to turn on a computer and

see a live performance on their computer. Is that a good thing?

HAMIET

BLUIETT: For me, I think it is healthier. I think the end result is that

people heard more live music than they do now, whereas now, it is not

like that. You had big bands running around, whereas now a days, you don't

have the accessibility to them. You could talk to musicians and they were

somebody you could meet and greet up close as opposed to everybody being

far and distant. So it has changed a lot, but personally, there are things

about the past I like and things I don't like. Neither one of them are

the ultimate. We need to go into something else now. That is where things

are headed for.

FJ:

What came first?

HAMIET

BLUIETT: The very first instrument that I tried to play was piano.

FJ:

How did that experiment go?

HAMIET

BLUIETT: It didn't go too good when the hands went in different directions.

I started playing piano when I was about four and so I knew how to read

music when I was four years old. I realized that that wasn't my instrument,

but I still fool around with it a little bit especially when I try to

do compositions. But the hands going in different directions, it didn't

really work for me because that was not where I was coming from. Then

the next thing I tried was the trumpet because I thought the trumpet was

a saxophone. I asked a dude in the school what the instrument was that

was shaped like a saxophone and he told me that that was a trumpet. So

I got a trumpet and it wasn't what I wanted, but it was too late. So that

wasn't my instrument either, but I learned the principle of the brass

instruments and how they kind of operate. That lasted about a month and

I went back to the band director and he told me that it was too late to

get a saxophone, but I should start out on the clarinet and that is the

foundation for the woodwind family and so I played clarinet for years.

I didn't get to the baritone saxophone until I was eighteen or nineteen.

But I saw one at ten and I wanted to play one. I realized that that was

the horn. It was love at first sight. I didn't hear it or nothing. I just

looked at it and that was the horn I wanted to play.

FJ:

What was it about the baritone that called to you?

HAMIET

BLUIETT: Well, I don't know. I didn't even hear it. There was something

about it. Like you look at somebody and you like them. I just fell in

love with the instrument from the sight of it. That was it. I never forgot

that it was a baritone saxophone. I always wanted to play saxophone, but

I had never seen anything like a baritone. So when I heard the guy playing

it, I wasn't that impressed with what he played. It was the size of the

sound because most people who play the baritone don't approach it like

the awesome instrument that it is. They approach it as if it is something

docile like a servant type instrument. I don't approach it that way. I

approach it as if it was a lead voice and not necessarily here to uphold

the altos, tenors, and sopranos. I think it can stand toe to toe with

you like Shaquille O'Neal and take you out. So it is a whole other kind

of attitude I had with it. I don't really have to have that attitude,

but once I heard Harry Carney play, I knew that I was right. I was about

in my mid-twenties before I finally heard him, I'm talking about him in

person. See, Fred, that's another thing too about not hearing people in

person. There is a lot of people out there running around singing that

really can't sing and their fans don't even know that. They've got such

good sound equipment that they don't really know that they can't operate

the way that you had to do in the past when you really had to be able

to sing. You've got somebody like Patti LaBelle that really can hit. I'm

not even dealing with a lot of other people like Ella and Sarah, who really

can sing. There is not really that kind of singing anymore. We can even

talk about the food. People think a McDonalds Happy Meal or number five

combo or whatever it is, is a meal, and I'm like no. The music you have

now a days, what they try to call jazz now, a lot of that stuff is like

toilet water. I think there has to be a certain something inside of you

from your gut that comes through that you really mean what it is you're

saying and people can feel it and hear it. That is starting to be very

much missed. It is really missing. We are in a crisis right now in a lot

of things.

FJ:

How do we stop the bleeding?

HAMIET

BLUIETT: Well, there is always going to be a solution, Fred, because nothing

is going to go on forever. They have got a lot of corporate action going

on in our music and the arts where the corporate people are making up

our minds about what should be done and making the decisions and the decisions

aren't really made by people who love art. That is not happening. It is

not going to keep on happening because it won't be able to sustain itself,

just like the Supremes' tour that they did. They though they were going

to be able to get away with it and it failed. If they had put the original

people out there that really can kick, people would come out. But since

they didn't do it that way, it's not happening. That is the corporate

decision, whereas the decision should have been that if they didn't have

the original people, then they shouldn't have done it, period! That would

be an artistic decision. That is a classic example. Every time they've

tried to do that, it has only lasted for so long. In my way of looking

at it, Fred, people are very starved for really great art. It is really

getting bad. It's been bad for quite some time. Nothing is hopeless and

I don't have a hopeless way of looking at it. I am just talking about

what I see. By the grace of God, things are always going to right themselves

anyway. It is not going to last. Art is not sustained that way. It won't

hold water and it won't float. No, no, it won't work. It is not going

to work, but they keep on trying it. That is something like me and other

people that I know that are dedicated to just being true to themselves.

We will just have to endure, become stronger, and stand and sustain and

go on through.

FJ:

Has it been an uphill battle arguing your point about the pros of the

baritone?

HAMIET

BLUIETT: Almost impossible. Look, Fred, I don't call myself a jazz musician.

I don't want to shove my horn back down and make it sound like an alto

or play it like a tenor. It is a baritone. The guy that I really admire

on the baritone was Harry Carney. Duke Ellington really understood that

instrument. Duke had the horn play melodies. He didn't have the horn playing

support. He had a big fat melody running around all the time, whether

he had Johnny Hodges play or Harry. Harry Carney played a lot of melody.

He wrote and thought about the instrument in a whole other type of capacity.

Even then, by putting all those instruments on top of it, you still had

it in a support role because you could stick a million horns on top of

it. That is when I realized how much power the horn had. I was sitting

a few feet from him and I heard all the trumpet players take solos and

everybody took solos all night. Three-quarters into the night, it was

pretty much over, he stood up and played one note and everything in the

place stopped. The cash register didn't ring, didn't nobody move, nothing

happened. He played one note that lasted quite a long period of time.

He hit the low note and the band came in and everything went back to as

usual. I said that this horn has got something else to it. Duke Ellington

had to be something else because one of the most magical things that I've

seen happen, happened in his band.

FJ:

Let's touch on your association with BAG.

HAMIET

BLUIETT: When we did BAG, I came out of the service in 1966, in January.

I was in the Navy. BAG started in maybe '67. I left St. Louis in '69 because

it was over for me and I needed to come to somewhere else. So at the time,

when I heard the music that the guys from BAG got together with the cats

from the Art Ensemble, Miles said in his book that when he heard the music

of Charlie Parker, that the music went all up into him, and their music

went all up into me. This was time appropriate music that I was supposed

to be part of. A lot of things that they were talking of at the time really

made a lot of sense to me. It was time for something else to happen and

I was in the right place at the right time. I was waiting for the times

to catch up, but I always knew that it was right and it was next. I knew

Ornette was right and it was next. I heard Charlie Parker in the mid-Forties

and when I was a child, I knew it was right and it was next. I have always

been that way. I have always had a way of hearing what is going on because

you can hear the level or artistry and the commitment and honesty that

comes out of these cats. If people don't do that, you can hear that they

aren't doing that. You can hear that they are not doing anything new.

I think these people need to be propped up instead of knocked to the side

as if they are insignificant or not relevant. We were doing things like

we had multimedia stuff before I even knew that there was a word called

multimedia. A lot of times the name for what we were doing was given to

us later after we had already done it.

FJ:

And your time with Charles Mingus?

HAMIET

BLUIETT: It was like being in a hurricane. Sometimes the immense power

and the totality of the whole thing, Fred, let me give you an example.

I worked with Mingus after Coltrane had died. The kind of power that Coltrane

put out, this was the next band that was playing on that kind of wave,

in terms of just sheer power. Art Blakey had not gotten a hold of the

band that brought him back yet. Everybody was really conservative because

I'm talking about, when I was with Mingus, it was between '71 and '74.

I don't even remember everything. Sometimes people tell me what I did.

I've forgotten some of it. When Ornette premiered Skies of America at

the Philharmonic in New York, Mingus played with his big band, which I

was the featured soloist on. It was very strong music, extremely strong.

It ran the whole gamut of emotions, but the level was unbelievable. I

was really able to play with a master and the further I get away from

it, and by the way, at the same time, by the time I got of his band, I

hated him.

FJ:

Mingus gets that a lot.

HAMIET

BLUIETT: I didn't think about why I hated him. I guess I hated him because

I didn't stay in the band (laughing). I mean to really be truthful about

it. I left Mingus because I didn't want to play that music no more. Mingus

was something else. He asked me one time, "Is it the music?"

And I lied to him and told him, "No." It is the approach. We

had figured out a new approach to playing music that didn't use chord

changes. That is really the way that I wanted to play. I didn't want to

play a chordal or vertical way of looking at music. We had more of a horizontal

approach. It was different. It was something totally different going on.

That is what I wanted to be a part of. Mingus was dope. He had all of

that stuff in play and a lot more. Gil Evans asked me, "What are

you all doing? How do you all do it?" I showed him the music and

said, "This is what we do." He said, "There is no chords."

And I said, "I know because we don't use them." We used them,

but they are not a grid and you don't use chord changes as a roadmap and

that was different. You really have to have a lot going on for yourself.

It is really different.

FJ:

Your thoughts on the World Saxophone Quartet.

HAMIET

BLUIETT: The three of us had gotten together playing a thing with Anthony

Braxton the year before, which I almost forgot about. Later on, Kidd Jordan

came up from New Orleans in '76 and heard all these bands playing around

in what they called loft jazz. The whole had gotten turned onto this thing

called loft jazz, a whole creative community because it was actors, poets,

dancers, everybody. A creative environment germinates the brain of anyone

that is around, which is why it is so dangerous to people that don't want

you to think for yourself. It is so refreshing for people that do need

to think. It was one of those time periods. He (Jordan) came up and asked

the four of us to come down and play. His students wanted to hear something

different. They wanted him to get either Ornette or Sun Ra. Sun Ra was

a little bit too aloof business wise. He could never get to Sun Ra, no

way. It was too out. He couldn't deal with it. Ornette's price was too

much. They couldn't deal with that either. He brought up his horn and

so he was playing all of us. We all had bands and we were in each other's

bands. It was a really creative, fertile scene going on. It was unbelievable.

People were coming out of the woodwork and over in Europe to see what

was going on. It was time for something new to happen and everybody knew

it. Like it is time for something new to happen again. I can feel it.

You can always feel it because it is in the air. He asked us to come down

and we made a concert without the bass and the drums. We liked it better

without the bass and drums anyway. We had developed a style of playing,

either with a drummer or without a drummer. It didn't make any difference

to us. We were playing concerts that way. It was a lot of improvisation

and a lot of composition. Julius used to write extremely difficult, elongated

things for us to play that we had to work like a maniac, ten, twelve hours

a day, just to get them down. Henry Threadgill would write tunes and we

would work on them for four or five hours before we'd go play them. It

was a lot of work involved. It was not just some guys getting together

and doing anything. We talked about the music and what we thought should

be done. We started the group in '76, December and had this audience in

New Orleans. Terence Blanchard, Wynton Marsalis, Branford, you name it

was some of these youngsters in the audience, that whole crew, including

people up to eighty years old and down to babies. We hit and the energy

of the music was so out and everybody dug it and the children, they put

them down and the children started running. Kids were just running around

like a wagon train and nobody said anything to them. This music energizes

you. It doesn't make you sit still. You won't want to sit still because

it is hitting every part of your body, permeating you and you've got to

move. I think if people don't move, there is something wrong. If I don't

want nobody to move, I'll go play at a mausoleum. I think a lot of things

are backwards. I really do. Everything is all messed up. That is basically

how we got started. Folks were just watching us. Everywhere we would go,

people was watching. I remember, Greg Osby told me that he used to stay

outside the BAG building and he could hear us through the wall and how

much that impressed him. I had no idea that I had impressed this young

man.

FJ:

Next year, the WSQ will be celebrating twenty-five years.

HAMIET

BLUIETT: Twenty-five years. Yeah, I know. We've stayed together and did

basically what we had to do. The group has sort of kept itself together.

FJ:

Is it a creative source for you?

HAMIET

BLUIETT: Sometimes it is and sometimes it isn't. I can see where as a

baritone saxophonist for me personally, sometimes it has been a hindrance

because I need to take the horn out of the saxophone section in order

to get first ranking, but at the same time, it is something that I started

and whatever I start, I need to stand by.

Fred

Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and is an MTV icon. Comments? Email

Fred.