A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN

Jazz

artists pay a heavy toll for their art, more so than any other art form.

As for songbirds, I think of Billie Holiday, the one and only Ella, and

Sathima Bea Benjamin. All have suffered on some level for their artistic

integrity and that which their art has brought along. Married to Abdullah

Ibrahim (aka Dollar Brand), Benjamin should be in the mist of a wonderful

and luminous career, but like most things these days, unjust and tragic,

that success never fully developed for Ms. Benjamin. I always wondered

how a singer that was a favorite of Duke Ellington would not find the

gold at the end of the jazz rainbow, and so I called her and we spoke

at great length about her impressions of the times, then and now. It is

a candid conversation with one of the most unheralded singers of our time,

unedited and in her own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

SATHIMA BEA

BENJAMIN: I think I started as soon as my ears could take in things because

I was blessed to be born in a place where actually I believe that there

was music in the air. There was just such beautiful musical place. There

was real musicality and I was exposed to that at a very early age. I kind

of believe that if you are going to be a musician, you must be born that

way. Maybe other people would hear all those things and it would not mean

as much, but if you have the tendency to pick up on the vibrations, this

musical vibrations, then you are going to pick up everything that's around

you. I mean, there was music in the streets. When I was young, people

would go around singing out whatever it was they were selling, be it vegetables

or fruits or fish or whatever. That was constantly happening in the streets.

We have a thing that goes on every New Year's in Cape Town and I think

it originated a couple of hundreds of years ago. What happens is that

ever year during New Year's, we have thousands of people that put the

current hit songs of that year and put it on top of Cape Town rhythms,

which is hard to explain. Some people think it is a samba, but it is not

quite. The rhythm comes from all the diverse people that are there. We

have Indonesians. We have African people. We have people who came from

all over to settle there. I fall under that label when we were classified.

We don't do that anymore because we are a free South Africa now.

FJ:

That wasn't always the case.

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: Oh, good gracious, I think it is only free when

Nelson Mandela was out, which was about eight years ago and the government

of the day came into power and then we obtained freedom.

FJ: It is always a difficult thing to think that less than a decade ago,

there was oppression to people of color in South Africa.

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: I, myself, drew similarities when I was a teenager

to this country. I started listening to the music of the then so called

Negro or colored people in this country. I felt a kinship for also being

labeled. The kinship came, of course, with that feeling because the social

structure seemed somewhat the same and I could identify with that. I guess

it led me to the music, which is jazz, which is what liberates you. It

is the most liberating music on the planet. You will then find in a way

to rebel against that for want of a stupid word. It is your spirit that

needs to survive with all that labeling and the stigma and all the cannot

dos. You cannot do it because you are second rate and maybe you shouldn't

even be alive. You have to seek a way to liberate yourself from all of

that.

FJ: Your way was through the music.

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: Absolutely. It is what saved me.

FJ:

But why this music?

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: Well, Fred, first of all, it was a music that allowed

you to express yourself. I wasn't writing my own music, but you could

take any song and do it the way that you wanted to do it, not the way

anyone else did it and that was very important to me. Listen, we had just

wonderful talent down there in that country. There were people who could

exactly imitate. You couldn't even tell between the real thing. That didn't

appeal to me, to be an imitation of somebody. What I felt I needed and

I felt a long for, which is to express myself as uniquely as possible

and that is what jazz affords you. That is the wonder of that music, that

you have such freedom. Freedom is very misconstrued in a way today. You

have to understand that if you are working with an art form or if you

are working with the music, you have to respect where it came from. Where

it was at that moment and where you think it could go. I don't know where

jazz is going. I think it will just evolve on its own. It will just keep

evolving. People take it and say that that is what they want to do because

that is just freeing my soul and that is a wonderful thing to feel free.

I don't suppose that every person who is into music will want to be a

jazz musician because it is probably the hardest thing to do in the world.

FJ: Why do you feel it is so demanding?

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: You would dare, you would dare to be different,

to be absolutely different on your own. Of course, the wonderful thing

is you are going to meet other people who are daring the same thing. It

is just such a democratic unit, a jazz unit, if it is done right. Each

one has a voice. There is a central theme and you make a whole. It is

such a sharing thing. It is such a community. Can you imagine if the whole

world was run on these principles? It is a dangerous philosophy in a way.

FJ: Let's touch on your association with Duke Ellington.

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: I think I first met Duke Ellington when I heard

his music and I instinctively went toward his song. I must have been about

twenty years old at that time and still living in South Africa and singing

wherever I could. We didn't have much in the way of jazz clubs. I worked

with colored musicians in the forbidden areas. It wasn't jazz clubs. It

was more like nightclubs. We had the stage to ourselves all night long.

People were dancing to what we were doing. We used it as a great place

to get our thing together because we couldn't afford rehearsal spaces

or anything. So we would do everything there while we were doing the gig.

It was more like nightclub entertainment. It wasn't only his music. It

was whatever you read at the back of the album that you managed to get

a hold of. I don't know about other people, but I absolutely revered who

this man was. I felt a kinship again there with the African-American experience.

I felt how great he was. It was the just the sound of that band and the

harmony that it was, the harmony that just came through. It was like such

a harmonious family. I think it was the beautiful melodies and harmonies

that attracted me most. I felt he was the master. He was the master of

this music.

FJ: Has anyone come close?

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: I think my husband.

FJ: Let's talk about your husband, Abdullah Ibrahim.

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: He has the same type of personality and the same

way with him that Duke Ellington had. We met in Cape Town. He was the

pianist for some sort of variety show and I was in the audience and that

is how we met. I told him I was going to sing "I've Got It Bad (And That

Ain't Good)," which was a Duke Ellington song and he couldn't believe

it because he said that he was working with the same song. The only thing

is that I was doing it in another key. That is what started us working

together. So in a strange way, it was a song of Duke Ellington that actually

brought us together. The friendship grew and we started a Sunday evening

jazz session club. We found this beautiful place and it became a place

for jazz musicians to come and do their thing. We never made any money.

It wasn't about that. It lasted about a year and by that time it was 1960

and the government clamped down on everything. There was just no way you

could have any work, no way. That's when we decided to through a friend

that we had met, a Swiss graphic artist that said that if we had ever

thought of leaving that he would try to help us. We remembered that and

I think it was two years later in 1962 when with the help of friends and

family, we managed to scrape together enough money to get out of there

because it was really bad. There was just no work. There was just no work

at all, not even in the nightclubs, although Abdullah never played in

those nightclubs. He was so into his own sound and his own thing and I

think he has influenced me a great deal in showing me the way and making

me feel that I was on the right path. It was just kindred souls meeting

at the right time.

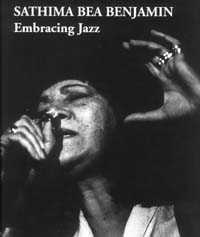

FJ: Let's touch on Embracing Jazz, the book and the companion CD.

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: It was suggested to me by a fan of both my husband

and myself and he has done a discography of Abdullah. I think that was

two years ago. I don't even know that it is in the bookstores, but it

should be because Abdullah has done about a hundred recordings. He suggested

doing the same with me, but I have only done about eight. He asked if

he could use my songs to put into the book and do a chapter on Cape Town

and one on Europe and he would come up with a book and he did, so I have

him to thank. I had no idea that someone in the world thought that highly

of me and it made me feel wonderful. It is his book and it is his work

and he is now trying to get a distributor.

FJ: Your thoughts on the state of the music today.

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: What I think is missing is a very important element

and that is spontaneity. It doesn't mean that everyone has to jam. I don't

mean that. I think you have to have some kind of form. You have to have

some kind of an idea. It should really be very much just in your head

and your soul. I write songs, but I can't technically write music. Everything

I do is intuitive. I'm not a prolific composer. I once thought that maybe

I should go to school and learn how to do that, but I changed my mind.

I think that it might interfere with my receiving whatever I have. I think

that element of spontaneity is a very necessary ingredient to get this

feeling across, to get the feeling of the music out there. It is not even

about emotion. It goes far deeper than that. I think jazz is also about

how you feel. There is a spirit in there and you have to work with that.

When I hear some of the music today, I am missing that very, very much.

I've really been very fortunate that whenever I've recorded or whenever

I've worked, I have always gotten something back. I know that I have given

joy at the same time.

FJ: Do you take comfort in that knowledge?

SATHIMA BEA BENJAMIN: Yes, it does, but it also fulfills me knowing that

it comes back to me. So it is like a double thing that happens. Maybe

people should run business like this. Jazz is just the way to go. It is

almost like a religion. You have to consider your gift a very sacred thing

and that you shouldn't mess with it. You pay a price for being that devoted.

I think I have paid a heavy price, but I get so much back.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and can't define the word jazz.

Comments? Email

Fred.