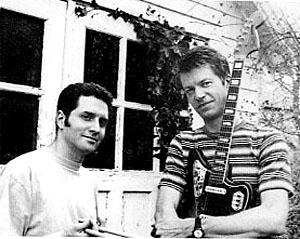

Gregg

Bendian and Nels Cline

courtesy of Nels Cline

A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH GREGG BENDIAN

Did I tell you my Interstellar Space Revisited story? For the benefit

of those whom have already heard this story, I will make it quick. I was

in Boston, found a copy of it in a used record bin, bought it, listened

to it all the way through the mammoth plane ride back to Los Angeles,

and could not stop harping about it. Gregg Bendian was the other half

of the duet (along with Nels Cline). I don't know what I like more, Bendian

on the vibes or Bendian, the drummer. Luckily, we all don't have to choose.

Bendian is both. I will let him tell you, as always, unedited and in his

own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

GREGG BENDIAN: Well, I grew up in a home that was full of music. My parents

were not musicians, but they are music lovers. They listened to everything

from classical music, Tchaikovsky, Bach, Beethoven, to Miles Davis and

Thelonious Monk, to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and I heard a lot

of jazz, classical, and rock music growing up, so to me, it was a normal

thing to be interested in a wide variety of music. As I got into the age

where I wanted to pick up an instrument, I decided that I wanted to play

the drums. I was very interested in playing in a rock band, but at the

same time, I was playing in school in the orchestra, playing timpani and

playing classical snare drums. So as I progressed into junior high school,

I had a rock band. I had an improv group that experimented with different

kinds of sonic improv and worked with films, worked with poetry, worked

with dancers. And throughout high school, I studied classical music in

terms of composition and percussion, so I was writing chamber music and

orchestral music, in addition to playing in jazz and rock bands. When

I got to college, I thought I would make a decision as to which of these

areas I was actually ultimately going to be specializing in. I never made

that decision because I thought it would be more fun to make up a kind

of music that could combine all of my interests and all of my skills and

invent an original music of my own that would deal with composition, deal

with improvisation, deal with jazz, deal with rock elements, and sort

of bring it all together in a band. And now, each of my different bands

draws on different areas of inspiration from all of these styles of music

that I just spoke about.

FJ: Were you getting paid gigs at that age?

GREGG BENDIAN: Well, I had a group in high school playing original music

and we often got paid to play so I guess that is a professional gig. The

first big time people that I played with was Derek Bailey when I was nineteen.

I played with him and also with John Zorn. And then my first big break

for recording was Cecil Taylor when I was twenty-three. I recorded In

Florescence with him for A&M Records and it was actually a really big

break for me because he recorded two of my solo percussion compositions

on this major release.

FJ: That makes you tread water in the deep end right from the outset.

GREGG

BENDIAN: Well, I always knew what I wanted to do, but I've been lucky

because it's been reinforced by having contact with a lot of really great

musicians that dug what I was doing and were very supportive. While I

was working with Cecil, Max Roach heard what I was doing and he told me

and a bunch of people that he thought I was doing a really good job playing

Cecil's music and coming up with my own approach to it.

FJ: Pretty high praise.

GREGG BENDIAN: Yeah, and when you have encouragement like that, it is

in some ways, very easy to keep going because you know you are onto something.

FJ: Let's touch on your work with Cecil Taylor and how his percussive

method to playing the piano and the density in his music shaped your outlook

on your own approach.

GREGG BENDIAN: Well, he taught me that any instrument can be an orchestra.

You can be playing by yourself and

still be presenting multiple voices and multiple musical ideas. I've tried

to lend that approach to anything that I am doing, whether it is playing

vibraphone or playing timpani, or playing drum set, playing percussion.

The other idea is that you can create new ways of creating sound on your

instrument, producing sound on the instrument, rather than just thinking,

"Once I've learned all the traditional ways of playing, then I have done

my job." The idea is to take the traditional ways and try to push them

a little bit further as well. Ultimately, I learned that you didn't have

to limit yourself in any way musically because Cecil's influences were

Stravinsky and Bartok and Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk and every

kind of music that you can think of and he wasn't ashamed of it. And my

influences were rock music, fusion music like Mahavishnu Orchestra, and

Miles Davis and I didn't have to be ashamed of that. I could actually

use whatever I learned from their music in my own style of music. I learned

that from Cecil and from a number of other people that it is really what

you do with the material. It is not that some stuff is cool to listen

to and some stuff is not.

FJ: How can a drum set be an orchestra?

GREGG BENDIAN: Absolutely, because the drums are such a multi-faceted

instrument. You have the drum head surface. You have the rim. You have

the shells. You have the cymbals. You have all the different angles that

you can strike the cymbals at. You have all the different parts of the

stick, all different parts of your hand that you can use to strike the

cymbals. You have all different types of mallets and brushes. Right there,

putting that into music is orchestration. You're treating the drum set

as a gigantic conglomeration of instruments rather than just the rhythm

keeper.

FJ: So you have a more panoramic approach, as opposed to a narrow approach?

GREGG BENDIAN: I try to have a panoramic view of every aspect of music,

whether it be composition or playing or listening. I am trying to be open

to every possibility. Now, that sounds like a tall order and it is, but

at the same time, just the effort of being open to all those things allows

you just a wealth of possibilities. So I don't run out of ideas. I don't

get bored. I don't tire easily in terms of my pursuit of music. Each project

I do, I have different ideas that I can explore.

FJ: Although that openness allows for moments of brilliance, it also must

be very exhausting mentally to have to continually explore every single

nook and cranny?

GREGG BENDIAN: It tires me physically too, Fred. Almost every group, like

I am doing this week the piano trio and my duo with Nels Cline, playing

the music of John Coltrane's Interstellar Space and I am doing my group,

Interzone, which I play vibraphone in. It's very challenging to say the

least, to keep up with all those setups and all of that material and then

as soon as I get home, I start working with this guitar player, Richard

Leo Johnson and that is an all acoustic guitar and percussion duet. When

I get off of that tour, I start working with Ornette Coleman. I will be

playing timpani in his group. So it is constantly shifting gears. It is

constantly trying to keep up without losing it.

FJ: With all those balls in the air, what keeps you from burning out?

GREGG BENDIAN: My love of music. I get no other kind of joy than when

I am playing music. There is nothing like it.

FJ: Is it that simple?

GREGG BENDIAN: Yeah, it is that simple. I am certainly not in this for

the money.

FJ: No one is in this for the money.

GREGG BENDIAN: I've always been motivated by my excitement and love for

music and the things that it has taught be about life and the world and

people and the way of relating my innermost thoughts to people.

FJ: What life lesson has it taught you?

GREGG BENDIAN: That the individual is a very valuable part of society

and that having your own voice, having your own point of view, having

your own way of looking at life and approaching life is as valid as the

tons of people that are all trying to duplicate each other and be the

same. It's given me self-confidence in pursuing my own unique vision because

the more I give to it, the more it gives back to me in terms of my feelings

of self-worth and my confidence and my feeling that I am onto something

that is worthwhile because people have responded very strongly to my music.

We're not talking about thousands and thousands of people, but we're talking

about the people that have heard my music and have said to me, "What you're

doing is very unique and special and we like it." You can't trade that

for a million dollars.

FJ: As with anything throughout the history of man's existence, anything

uniquely individual has been feared.

GREGG BENDIAN: Oh, yeah.

FJ: Having said that, don't you feel your life would have been easier

if you had just opted to play like Elvin Jones or Roy Haynes?

GREGG BENDIAN: I could play like Roy Haynes, but I can't. You see, Fred,

the other thing is my life would have been a lot easier, yes, if I could

duplicate what has already been done and do it in such a way that makes

it something that could be very sellable and an easy commodity. But I

would have missed all the chances for self-discovery at the same time.

FJ: I was in Boston last summer and ventured into a used record store

and came across a copy of Interstellar Space Revisited: The Music of John

Coltrane on the Atavistic (www.atavisitic.com)

label and I purchased it as a whim to listen to on the grueling flight

back to Los Angeles. I must have listened to the recording from start

to finish four times over. What possessed you to put your ass out in the

wind and invite all the scrutiny that comes

with doing the music of Trane? And although it has come late, you must

be pleased with the overwhelmingly positive response it has been getting.

GREGG BENDIAN: All I can say is two things. One is I am thrilled it has

taken off the way it has because I rarely, if ever, do other people's

music or try and interpret what would be considered a masterpiece. But

since we really went out on a limb to do it differently, rather than trying

to recreate it. We tried to pay respect to it, but at the same time, show

that the material figured into our lives in a special way. How we were

going to approach the music. How I grew up listening to Rashied Ali and

what that had to do with how I play the drums when I play free jazz because

playing with Cecil, playing with Brotzmann, playing with Roscoe Mitchell

and Evan Parker, all of those guys, the way I played their music had something

to do in some small part or even a bigger part with my listening to Rashied

when I was in high school. So to be able to do a record of that music

and not feel like I had to duplicate what Rashied was doing, but confident

in knowing that what I was doing had some of Rashied in there, but also

had my own approach. I felt like I was building on the tradition, not

just aping it. I had a feeling when we were doing it that we were onto

something, but we were also concerned that people would think, especially

based upon the use of electric guitar, that people wouldn't necessarily

understand where we were coming from on this. But Nels and I did our homework

and when people reacted as positively as they did, we felt a real sense

of satisfaction because they could hear the real intensity that we were

putting into the music. It also opens up the question of checking out

the later music of John Coltrane, which a lot of people don't do. If they

do a Coltrane tribute, they do the same five tunes, "Giant Steps," "Naima,"

"My Favorite Things," and I always said, "What about later Coltrane?"

They say, "Well, we're not interested in that." And Nels and I wanted

to say that this is an important part of his work. It is the later period.

Why did he move in this direction that he moved? Maybe there was a progression

in jazz? So it was a much larger, even somewhat political statement for

us to do this recording too. We didn't want to record the normal tunes,

although we did include "Lonnie's Lament" as sort of harkening back to

some of the more modal stuff.

FJ: Has Rashied heard the record?

GREGG BENDIAN: Yeah, Howard (Howard Mandel) played it for him. Rashied

flipped and he just loved it.

FJ: That is enough validation.

GREGG BENDIAN: It was very, very exciting because he was just blown away

by it and he couldn't believe that we bothered to do the whole suite (laughing).

FJ: Having researched the later years of Trane's music, was he about to

venture into more uncharted waters?

GREGG BENDIAN: He surprised people when he went into the direction that

he went in. So we would like to hope

that he would keep going in that direction, but as an artist progresses,

there is a certain amount of re-exploring and re-evaluating some of the

past works. If he had another ten or twenty years, eventually, well, he

was even doing that with the quintet with Pharoah, playing "My Favorite

Things" again and playing "Naima" again, but with a different approach.

So that is of interest too that he would actually go back and say that

it was all part of the continuum and it is not just like that was then

and this is now.

FJ: Does that echo your feelings?

GREGG BENDIAN: I do. I've actually re-recorded different versions of some

of my pieces, like the piece "Current," which is on my Counterparts (CIMP)

CD is also on the new trio CD. That is a different version. The piece

for David Cronenberg ("Interzonia 1") is on the new Interzone record (Myriad,

on Atavistic), but I originally recorded that almost ten years ago.

FJ: Let's talk about the new Interzone record on Atavistic, Myriad.

GREGG BENDIAN: We recorded it about two years ago and then I took a long

time to come to mixing it and putting it together for release. It was

a long time working on the music and preparing it and so it was actually

an unusual situation for me, in that we were putting it together in the

studio.

FJ: Do you see yourself playing either the vibraphone or drums exclusively?

GREGG BENDIAN: It is a tricky situation for me because everybody who plays

both tuned percussion and drums want me to always bring along the vibraphone

or bring along a glockenspiel or have some tuned percussion elements in

the music and very often, I like to concentrate on either drum set or

vibraphone. In some of my groups, I have played both vibraphone and drum

set and in some groups that I have been hired to play in, I do play both.

But there is so much that can be done with either the vibraphone or the

drum set, that it almost is too much so that you end up getting a wide

variety of things without any particular focus on one or the other, depending

on the group situation and the nature of the music. Right now, I tend

to prefer to be playing one or the other. That is why in Interzone I originally

played both drum set and vibraphone and so that Alex Cline and I would

be playing drum sets together at times. But that ended up being something

where I was more interested in having Alex cover the drums and letting

me play vibraphones so that I could actually force myself to explore as

many options on the vibes as possible. And then on our duet recording,

we do some solo drum set stuff, but we mostly do vibraphone and drum set

duets.

FJ: Has the audience for advanced improvised music grown within the past

couple of years?

GREGG BENDIAN: I think so. I think so. I meet a lot of young people that

are interested in the music and I meet people who have been listening

to my work since the Cecil days. This is a special kind of music. It does

not attract every person. It's not for everyone. It grows slowly. I wouldn't

say that right now, I feel that there is the explosion. It is not evident

in terms of the financial component. In terms of interest, yeah, I think

that there is a big interest for it right now because a lot of young people

are tired of listening to corporate rock and corporate jazz and mainstream

pop. Alternative music is no longer alternative. It is just a name. So

we are offering an alternative to alternative.

FJ: Gage the impact a Knitting Factory here in Los Angeles will have,

if at all.

GREGG BENDIAN: Well, all I can say is that the musicians that have been

playing creative music on the LA scene have been doing it way longer than

the Knitting Factory has been in existence on any place on the planet.

That they will continue to do so after the Knitting Factory is gone and

I think if there is any sort of give and take that is possible between

the Knitting Factory and the creative music scene in LA, that will be

great, but it is important for everybody to realize that it is the music

that is the main thing and not the package or the label. Very often people

get sucked into thinking that a recognizable moniker for a style of music

is actually an object or a product, but that then diminishes the individual

and this music is about individual. This is the same thing in New York,

the music scene in New York was around forever before the Knitting Factory

and it continues to thrive in other areas besides the Knitting Factory.

So I personally don't think that the Knitting Factory is the be all and

end all.

FJ: Is there a pinnacle that you strive to reach?

GREGG BENDIAN: Well, that implies an ultimate destination and I can't

imagine that. Firstly, because I wouldn't want to imagine that and also

because I don't think it is possible to imagine that or to think of what

that might entail. For me, I just try to make the next project better

than the last one. To keep improving on the details within my playing,

my improvising, the details within my writing, my writing suiting the

bands that I work with more and more. Continuing to work with excellent

musicians. Practicing new ideas so that I am not regurgitating the same

ones over and over again, just like Lester Young said, which I love. He

said, "I try not to be a repeat offender." I try not to regurgitate and

repeated present the same material, but rather come up with new material,

new approaches. That is why the new Interzone record, Myriad, is so different

from the first one. There is a lot of commonality between the two, but

at the same time, it is more of rock edge to it too because I was embracing

more of my rock or prog rock, fusion kind of influences. The first one

is almost more of a Benny Goodman kind of approach to the guitar and vibraphone

combo kind of idea.

FJ: There is beauty in simplicity.

GREGG BENDIAN: I think so.

Fred Jung is the Editor-In-Chief and admires anyone who takes on Trane's

free period. Comments? Email him.