Courtesy of

Bob Belden

A FIRESIDE

CHAT WITH BOB BELDEN

Bob

Belden is jazz's Spiderman (bet he's never been called that one). His

Peter Parker, during the day life is as a producer bringing to life the

work of Miles Davis for the reissue arm of Columbia Records, Legacy. His

alter ego is as a saxophonist and he is an impressive one as evident by

his performance on Tim Hagans' Audible Architechture. He sat down with

the Roadshow from his home and we spoke candidly about his work with the

before mentioned Hagans, his thoughts on Miles, and his take on Ken Burns'

Jazz, as always unedited and in his own words.

FRED

JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

BOB

BELDEN: When I was three years old, I just started mimicking my brother

and sister's piano lessons. My brother played in a band in high school

and I was in junior high school. He started playing in a marching band

and I started playing in the junior high band on the saxophone. I went

to North Texas State, basically, so I could get out of high school a year

early. I got totally excited about jazz when I was at North Texas. Thousands

of music majors and music students were at North Texas. They had fourteen

big bands. They had a lot of jazz musicians and the record store was pretty

current. You had a lot of musicians who were really into being musicians.

And it was a great environment. It was just amazing. We had a library

that was ridiculous. Plus, I was a composition major. I was not only getting

jazz. I was getting contemporary classical music. I was studying orchestration,

counterpoint, as well as jazz and I took jazz arranging. I was never a

jazz major. I was a composition major.

FJ:

What intrigued you about composition?

BOB

BELDEN: You know, to be honest, Fred. I think the first time I really

wrote something was, remember that group Chicago?

FJ:

Peter Cetera is a staple in my home.

BOB

BELDEN: Remember, but I think it was their second album. No, it was their

first album. They had this like little chamber music in the middle (Chicago

III), like the "Approaching Storm" and some little chamber pieces.

And I remember my brother had it. They were just getting turned onto that.

So this is like around '67, '68 and I remember writing a couple of pieces,

like little small pieces, based on that music, those small little pieces

that Chicago wrote. And I just really enjoyed it and so I did some improvising

into a tape and I started doing marching band arrangements when I was

in high school and then big band arrangements. I played in a youth band

and actually, in high school, at one time, when music programs were encouraged,

in my area alone, we had my high school band. We had a region band. We

had a county band. We had honor band sponsored by one music store and

some of those had jazz bands. I was able to go and sit in on anybody's

instrument, in anybody's chair, in any of those groups and play the music,

electric bass, guitar, timpani, trombone, tuba, clarinet, flute, saxophone.

It was encouraged then. I went to a music camp when I was fifteen and

I studied some orchestration there and the concert band played strictly

music written for concert bands or classical transcriptions. So in 1967,

'68, I was listening to a lot of classical music, some jazz, a lot of

pop music, a lot of soul music. I was like twelve, thirteen years old.

FJ:

Let's touch on your time with Donald Byrd.

BOB

BELDEN: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. Well, Byrd is an interesting character because

he comes from a rich family background, in terms of knowing what the deal

is. His band with Pepper Adams was stunning. I have always been a fan

of even the stuff with the Black Byrd. Byrd really never, I think Byrd's

career is basically a couple of different parts. He was an up and coming

guy in New York in the mid-to-late Fifties and by the early Sixties, his

band was right up there with Miles in terms of sound and getting a quality

sound. And Byrd told me that he used to sub for Miles when Miles would

cancel. I think by '64, when he went to France and started studying and

the jazz scene was changing for him, he went into teaching. And I have

some of the early Black Byrd stuff, when they were in Montreux in 1970,

'73, and they were playing hardcore. Byrd changed his direction in the

late Sixties, but he was the first guy, like everybody was trying to crossover,

but he was one of the first guys who really did it and managed to find

a happy medium. I mean, the Black Byrd record is great. It's the Mizell

brothers (Fonce and Larry) and Harvey Mason and Chuck Rainey. It is a

real silent bass and that is like one of the best records of that thing,

but that is what Miles always wanted to do. He wanted to get Donald Byrd's

audience.

FJ:

Is Donald Byrd's Ethiopian Knights, Street Lady, and Black Byrd days the

cause for him being slighted critically and historically?

BOB

BELDEN: Oh, totally, Fred. There has always been a vibe against the guy.

There has always been a vibe against the guy and it is unfair. He is a

very smart man, a very funny guy and he went through it before Freddie

Hubbard went through this thing with the chops, having problems with your

chops. The trumpet is not an easy instrument and when you are juxtaposing

trumpet playing with teaching and with traveling and just being involved

with things, sometimes, you just don't practice enough. I remember once

playing a gig with Byrd. It was with my band in Houston, Texas, at some

place just south of the Astrodome and needless to say, the audience was

expecting the Black Byrds and they got the doves. But Byrd turned around

to me and said, "Do you want to play a Jimmy Heath tune?" I

said, "What?" And he said, "Gingerbread Boy," and

so we started playing "Gingerbread Boy" and he turns around

to me and says, "Now, I am going to play it like Miles," and

he played it like Miles Davis in the mid-Sixties. I said, "Byrd,

I am not going to bring it up ever again." And so it meant to me

that he was aware of it because he was one of these guys that was hyper-intelligent

and because of that, it defies the basic roots of jazz that you are a

pimp, drug addict asshole.

FJ:

Do you find in the same ways that Byrd was essentially discriminated against,

so too are your recording efforts because they are not "in the pocket"

and critically friendly?

BOB

BELDEN: Well, I have no idea of any kind of criticism, Fred, because I

really don't pay much attention to it. I have read some bad reviews, but

sometimes with bad reviews, people say what is on their minds. Besides,

I need to know who to hate (laughing). With the internet, you can find

out where their grandmother's retired at. Yeah, I don't care because I

am just amazed that I have gotten this far in this business as it is.

FJ:

You are certainly capable of playing "in the pocket" as clearly

evident on your work on Tim Hagans' Audible Architechture. Why don't you

play more straight-ahead and appease the critics?

BOB

BELDEN: Oh, well, let's see. I did a record on Sunnyside, two records

on Sunnyside, which are kind of straight-ahead. I mean, I've got so much

good stuff that these guys, they were living their music. They were living

the thing. To me, I've always been able to differentiate between what

is somebody else's stuff and what's mine. And Tim and I, we want to play

more straight-ahead kind of stuff, but we don't want to record it and

put it out because we have already crossed the path. We went with Animation

and Re-Animation. We crossed that path. I mean, for me as a composer,

I'm going to write music and it is going to contain straight-ahead, but

it is going to contain some other stuff, classical music, soul music,

the whole thing. I don't think anybody has made a real, I mean, there

is a handful of really quality straight-ahead records and if you notice,

it is generally by, I mean, Dave Holland's record comes to mind. That

is straight-ahead. That is probably one of the best. And in the last five

or six years, yeah, probably in the top five, but it is hard to find cats

who play that way, that play really straight-ahead where the feel is the

same. I work with Joe Chambers a lot. I did a film score and I had him

play on the film score and it was just swinging. It was like the most

beautiful glide and we were playing that kind of music because it was

required by the film and that is the real deal. You get some other cat

and it ain't the same.

FJ:

Well, Joe is the real deal.

BOB

BELDEN: If you look at things like the guy who is the real deal on sound,

he is a unique kind of cat. I've worked with Jack (DeJohnette), Tony (Williams),

and Joe Chambers and I think Joe is probably the least appreciated.

FJ:

As an arranger, how do you go about taking Puccini's work and placing

your own characteristics on compositions that have been recorded and rerecorded

countless times?

BOB

BELDEN: It's the melody.

FJ:

Does that hold true with Prince and Sting?

BOB

BELDEN: Well, with Sting, I went into, I got this recording deal based

on having played a gig and Matt Pierson came up to me and to keep him

informed if I had any ideas because he liked the band. It wasn't until

October when I went to see Sting and Sting did an arrangement of "Ain't

No Sunshine," and that got me thinking. He is obviously not opposed

to rearranging somebody else's music, so I went back stage and I said,

"I might do some arrangements of your music. I've got a band that

plays every night and if you want to come by and sit in, you are more

than welcome." I went home and fell asleep and woke up at like two

in the morning and a light bulb goes off and I went to Matt Pierson the

next day and got the deal, boom, like that. It was designed to take Sting's

music and try to make it sound like Miles and Gil. The Sting record is

kind of schizophrenic because the earlier sessions were really jazz oriented

and then the second session, we did three sessions over like two and a

half years, two years. The second session, I started bringing it in a

little bit, but the third session was like we were trying to make a commercial

song or two. And then the Prince record, there was one that came out in

the United States called When Doves Cry. That was totally commercial.

It was just an attempt to make a Stax/Motown kind of record. I had been

doing these arrangements for a Japanese company, transcribing stuff on

records. So I was like absorbing all of this pop orchestration stuff and

I had these pop tunes that I could kind of reconstruct like turning "1999"

into James Brown or turning "Diamonds and Pearls" into the Motown

stuff from Marvin Gaye, like really over the top. So I was taking styles

of arranging and taking songs and concepts, production concepts and then

packaging it for that, but you didn't hear Prince Jazz did you?

FJ:

No.

BOB

BELDEN: You see, that's the thing. I did two records during those days.

And Prince Jazz, one track is with Wallace Roney, Kenny Garrett, Mike

Stern, Adam Holzman, and Ricky Patterson, and then there is two tunes

with my band, which was Hagans, Kevin Hays, Jacky Terrasson, Rodney Holmes

and Larry Grenadier, and Jimi Tunnell on guitar. Then I did a couple of

tracks with the big band and then I did one long, kind of a free "Purple

Rain" with Calderazzo and Kevin Hays. So I was able to take the Prince

pop stuff and at the same time, recorded some other stuff. Plus, I recorded

about an album of my own material. I recorded some of the Puccini stuff.

Puccini was all about melodies and operas. I had written this album with

the idea that you have a story and there is a continuation of this story.

With Puccini, it was the story of the melodies linked up and they continued

all the way through. It was incredibly dramatic opera, probably the last

grand opera in that tradition ever composed. And Gil and Miles had wanted

to do Tosca and I remember in a jazz magazine article in the Seventies,

somebody went to his place and saw the score of Tosca, and I had asked

Gil once, "Why did you guys not do Tosca?" And he goes, "There

wasn't enough there." And I remember, having the score of Tosca,

I looked in it and I know exactly what he was talking about.

FJ:

What wasn't there?

BOB

BELDEN: What wasn't there was developed melodies that went beyond eighteen

and nineteen bars. There were like six or so melodies and that was pretty

much it. There was a lot of dramatic music in there. Porgy and Bess, on

the other had, had melodies and it had bridge music that was done in popular

form and it was much more adaptable to the idea of rearranging it. But

at the time, Gil was writing electronic music. He wasn't thinking or hearing

woodwinds, which I thoroughly understand. What Gil's dilemma was that

he did not want to rewrite his own stuff all the stuff. When you write

acoustic music and you come out of this jazz world, you are faced with

a lot of ghosts and footprints. Sometimes, you get just a little too close

to the original thing, either your last record or somebody else's last

record.

FJ:

Congratulations on the Grammy nod for the Re-Animation project.

BOB

BELDEN: Oh, thank you, Fred.

FJ:

Contemporary Jazz is an odd category. Do the Grammys have to get with

the times?

BOB

BELDEN: Well, I have talked to some of the people on the committees and

they say that the word contemporary jazz used to be where they put all

the smooth jazz guys. Essentially, they re-looked at the definition of

it and it incorporates modern jazz and popular music into jazz. We certainly

do. This is dance music. It caused some ire last year when the smooth

jazz guys were kind of upset about it. Again, the reality of it is is

just the filling of the categories.

FJ:

You don't want Kenny G coming after you.

BOB

BELDEN: I would think Kenny G would be excited about competing against

us because it would legitimize him. He would go, "Yeah, look at what

they have me compared to." Even though we have our fingers down our

throat.

FJ:

You're no spring chicken, how did you come across techno?

BOB

BELDEN: Guys would ask me, I've been asked that a bunch and the reality

of it is that if you listen to drum and bass, you will hear this tempo

that is up here and very fast. That's bebop. It's Charlie Parker. Remember

acid jazz, Fred? Well, acid jazz never got up. It just stayed and plodded

on one little groove for ever and ever. For a jazz musician, you can't

play, if you come from that scene where you learn Trane and Bird, for

a saxophone player and Miles and Dizzy and Woody Shaw, if you are a trumpet

player, you can't just sit there and play blues licks. You want to play.

You want to burn. Drum and bass took us into that tempo zone. When I hear

it, I just hear Tony Williams. Tony Williams is what they all try to program.

I sent Tim some CDs and said, "Check this stuff out." We're

supposed to look for things to bring into jazz and we're supposed to look

for things to bring jazz into. Jazz to me is an attitude. It is not anything

that you can write down. It is like you can tell a jazz musician.

FJ:

How?

BOB

BELDEN: Because you will feel it. You will hear it in their music. You

will feel it in the way they deal with the music, the way they talk about

music.

FJ:

Who epitomizes a jazz musician?

BOB

BELDEN: Well, today, my friend, Joe Lovano. He is a jazz musician.

FJ:

Let's touch on your collaborations with Tim Hagans.

BOB

BELDEN: We worked together for a long time, since 1989. Well, first of

all, we don't work that much and so we don't have the stress of gigs,

which tends to cause band disfunction. We do most of our stuff in the

studio. We communicate about musical ideas all the time. We just generally

have fun. Everything is very humorous. It is the best of both worlds.

He is a nice cat and he plays great.

FJ:

You have been indispensable in assisting Columbia/Legacy with reissuing

Miles Davis material. In all the material and music that you have had

to sift through, what is the most striking thing about Miles that you

have learned?

BOB

BELDEN: Oh, a really, really, really sarcastic sense of humor. Oh, yeah.

There are so many misconceptions about him based on the public's reality,

but when you just deal with it on a musical level, you discover that he

was very, very focused. In certain periods of times, he wasn't for personal

reasons, but there was a time in his life when he was really focused on

music, the time when he was with Gil and Trane and then when he was with

Wayne.

FJ:

Miles, like no other person in the history of this music, has a personality

and aura that transcends the music itself. Will there ever be another

Miles?

BOB

BELDEN: No, because jazz is not mass media music. Miles was still involved

with mass media at the time. You're talking like the major companies back

then had tremendous influence on the press because they were the only

game in town and Miles got national media exposure on a continuous basis.

Nowadays, there is no focus on any particular person that will become

that status.

FJ:

Why do you feel those days will never return?

BOB

BELDEN: Well, I think that the cost of living, Miles was born wealthy.

Miles Davis could say no. Miles Davis could tell somebody to go shove

it. Miles Davis could do things that most cats can't do today because

he had money in the bank and when you have money in the bank, you can

say what is on your mind. He didn't have to make a living from playing

jazz and that gives you a totally different mindset.

FJ:

Favorite Miles record?

BOB

BELDEN: Filles de Kilimanjaro. It is just the closing of one door and

the opening of another.

FJ:

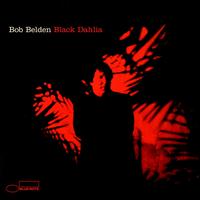

Let's talk about your soon to be released Black Dahlia.

BOB

BELDEN: I wanted to survive the recording session because it is a lot

of musicians in one day, a lot of money going down. The important thing

for me, I had been working on that for three years.

FJ:

Were you intimidated by the sheer scope of the project?

BOB

BELDEN: No, no, I am used to that. I produced the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra.

I look my time on that project and in the middle of the project, I got

really, really sick and I didn't think I would get through it and I recovered

and I had all this incentive to finish the record. So what you hear in

that record is somebody who went through a near death experience.

FJ:

What happened?

BOB

BELDEN: Oh, man, Fred, car wreck. Re-Animation was a month after the car

wreck. If you look at the CD, you will see a chair and a bottle of water.

I could only stand up to play solo. I was dehydrated from the trauma from

an automobile accident. I came so close to buying the farm, but I didn't

need the land (laughing).

FJ:

Have you been watching Ken Burns' Jazz?

BOB

BELDEN: Little snippets. For me, there is nothing new or insightful to

be gleamed from it. All the video footage from the artists that I am interested

in, I already have and I've seen all the still photos and I when I see,

it is funny to talk about things that you weren't involved with or you

weren't there, to see people fantasizing on film. One guy in particular,

who I shall not single out, goes into these really, really weird fantasies

about if Einstein and Coltrane were hanging out on the Left Bank. And

there is a point where jazz, again to me, is an attitude. It is not a

black and white film. And what I've seen of it, it looks nice. It is just

there is too much talking, not enough walking.

FJ: Were you asked to consult on the project?

BOB

BELDEN: I was involved with it a little bit. I saw the end of the credit

where they were talking about Miles, the wife beater and Louis Armstrong

had a hit with "Hello, Dolly," and I got a credit on there as

a consultant or something like that because I identified some tunes for

them and I worked on the single CD reissues that came out from Legacy,

but as far as having any editorial thing, no, because what I am interested

in, they don't cover. I think they talked about it for like five minutes.

It is causing much debate, which is a big bummer because I have a record

that is coming out and I don't want people talking about Ken Burns' Jazz

when my record is all about somebody who did die.

FJ:

There wasn't enough musical output from Miles, they had to find filler

by referring to Miles as a perpetrator of domestic violence.

BOB

BELDEN: They are just trying to demystify Miles. I mean, why don't they

talk about Louis Armstrong, who was a big pothead, who had Nixon carry

some reefer across our border. It is a cultural war. Ken Burns' Jazz,

if you wanted to define elitism, that is it. It is not John Zorn at all.

It is like this social context vibe, historical revisionism. It is not

about the music. It is about photographs and voiceovers.

FJ:

What peaks your interests now?

BOB

BELDEN: Well, I made the mistake of checking out Ken Vandermark because

Down Beat was writing so much about him and fortunately, they had a record

up at the listening station and I am glad I saved my fifteen dollars.

But some things do not interest me in the slightest and what I am interested

in right now, at this moment, besides doing stuff with the catalogs is

working with Tim and trying to get even further along the pike with what

we started with Animation. We are trying to shape our sound that derives

itself from a solid foundation, but involves today, modern technology,

which is about today. Miles Davis once said, "You live in a modern

house. You drive a modern car. You watch modern television. Why make music

that is antiquated?"

FJ: Would Miles approve of what Wynton Marsalis is doing?

BOB

BELDEN: Absolutely not. He would say, "What does he know? He wasn't

there." That is the first thing he would say. Anybody who was around,

ask them what they think about it. Go to the source.

Fred Jung

is the Editor-In-Chief, and is a fan of 70s Miles. Email

him.