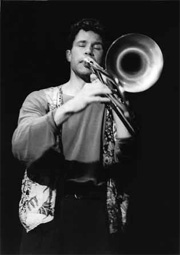

courtesy of Ray Anderson

Enja Records

A

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH RAY ANDERSON

The

trombone is an instrument that has always fascinated me. Perhaps it is

because I have always been attracted to that which the mainstream tends

to ignore and the bone is ignored by all accounts. I don't think Ray Anderson

minds do much though. He just marches on. That is why, by far and away,

Anderson is one of the most exciting players on any scene. People criticize

his flamboyance and critics rake him over the coals for his vocals. But

in the end, who gives a shit? The man gets his audiences on their feet

time and time again. He gives one hell of a show and when he is in So

Cal, I clear my calendar. Simply said, I personally love his playing.

Hell, I own every damn album Anderson has ever made, so I guess by all

accounts, that makes me a fan. And I am damn proud to say I am. So I give

you, Ray Anderson, my fav, unedited and in his own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

RAY

ANDERSON: I grew up in Chicago on the South Side, right in the shadow

of the University of Chicago, in Hyde Park there. That was a place with

a lot of music around. My jazz introduction came through my father's Dixieland

jazz records. He's not any kind of big jazz aficionado, but he likes Dixieland.

He had a couple of those Louis Armstrong records and he had some records

of trombone players that were the dukes of Dixieland. So I picked the

trombone based on the sound of it from those records. I started when I

was eight years old. I just never stopped (laughing). I took lessons from

the school and for a while, people at this university and I had regular

classical lessons. When you're a beginner, there is no difference between

a classical lesson and a jazz lesson. You are just trying to learn how

to make the sounds that the instrument makes.

FJ:

Coming from Chicago, you must have been up to your ears with the Chicago

blues?

RAY

ANDERSON: Yeah, one of the things about growing up in Chicago is you can't

do it without hearing some blues. So I was very aware of the Chicago rhythmic

kind of thing, Chicago blues thing. It is a wonderful influence. It is

a great influence.

FJ:

Who were some of the cats you were listening to?

RAY

ANDERSON: The preeminent cats right then in Chicago were Buddy Guy, Junior

Wells, Muddy Waters, James Cotton, all those folks. There is lots of blues

in Chicago and we used to have some blues band of this or that kind play

even for high school dances and these weren't people that we famous or

anything. So it is kind of like an atmospheric thing.

FJ:

Did you get an opportunity to listen to the AACM as well?

RAY

ANDERSON: Well, I left Chicago when I was sixteen, so I hadn't really

done much in the way of working or anything in Chicago. I had just that

year started working with some regularity in a horn section in a blues

band. I went to several AACM concerts. I remember going to hear Joseph

Jarman and Roscoe Mitchell playing duos and there was also an AACM place

out on the South Side, where I went several times and heard a bunch of

people. I don't remember who, but the stuff just completely blew my mind.

It was way over my head (laughing). I didn't understand it at all because

I was in high school and in high school, my thing was Dizzy and Coleman

Hawkins and even Coltrane was too much for me. I couldn't really figure

it out. Coltrane started to go out there with Ascension and Om and even

Countdown and records like that. I was like, "What is this?"

FJ:

When did you depart the Windy City for the Big Apple?

RAY

ANDERSON: In 1973.

FJ:

Chicago being a real blue-collar town, was it a culture shock?

RAY

ANDERSON: Well, it was tough in some ways, but I was really enjoying myself.

You know, Fred, in '73, when I came, I was twenty years old so when you

are twenty years old, you can do stuff like that, go to New York with

three hundred and fifty dollars and a couple of addresses of friends of

friends (laughing). But events transpired in a friendly direction and

pretty soon I was driving a taxi to make money and I had a room to share

and I started going around and sitting in. I was having a good time.

FJ:

Seems like a simple life.

RAY

ANDERSON: It was a simple life in some ways. That's true because there

was nothing to do but play and you had to just make enough money to survive.

That was easier in '73 in New York than it would be now. I lived on the

Lower East Side and the rent was never more than a hundred dollars a month.

You could have your own place for a hundred dollars a month. Now, this

wasn't necessarily a luxury place or anything (laughing). Pretty soon,

I was working a little of this, a little of that, a little bit of really

old fashioned kind of music with a ghost band of Tommy Dorsey's. I did

some of that and then I started getting into the Latin scene and I was

doing a bunch of that and some funk bands and stuff and meanwhile we would

just go out play all day, every day.

FJ: That has been the hallmark of your career, the ease at which you are

able to transcend genres.

RAY

ANDERSON: You know, Fred, that is a good point. I think it is really just

a question of personality. I just had the kind of personality where I

was fascinated by different sounds, different grooves, different forms,

different styles and I also had the urge to fit in. I had to urge to be

inclusive and to fit in. It kind of comes naturally to me. I didn't really

know anything about Latin music per say when I got to New York. Of course,

I had listened to some, but I didn't really know anything about it. I

had never really been working in that. I had spent all my working time

doing R&B and stuff. Once I started getting turned onto that, the trombone

is such a prevalent instrument and there are so many beautiful players

in there, I just got way into it. I just loved it. It just really absorbed

me. I didn't find that it was any kind of conscious decision, but more

just an affinity.

FJ: Are you just as much a student of the music as you were then?

RAY

ANDERSON: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. It is absolutely true. It is sort of a

platitude or whatever, but it is really true that the more you get into

music, the more you realize how you don't know anything (laughing). The

more you study it, the more you become impressed with your ignorance.

FJ:

Let's touch on your work with Anthony Braxton.

RAY

ANDERSON: I would say that Braxton is one of the really few and true geniuses

of music in this whole period that we're in. And just relating it to that

stylistic thing, Braxton is different than I am in that his position is

all encompassing and he really has the courage of his convictions. In

other words, he plays his music. It is not possible that Braxton would

go and learn how to fit in perfectly with a Latin band or something. He

is a cat that really has a lot of creativity and a lot of his own music

and is one of the people that is willing to go down with the ship. He

has that courage of artistic conviction and as such, he's just an unbelievable

inspiration. I learned a whole lot from this guy, just really in terms

of specific musical things, the way he has the different voices in the

quartet that we were in and how to react and the book itself, just learning

the book when I first got in the quartet expanded the technique and ability

enormously because the stuff is really difficult, even trying to play

it was a big learning process, but then to also be around Braxton. I spent

about four years, more or less, with him and during that time, his music

evolved enormously. He stopped doing the quartet thing with bass and drums

and of course the audience didn't really like it. When we started, we

did a whole tour with Anthony and I and Richard Teitelbaum on synthesizer.

So no more swing based things and stuff. This was just out there in terms

of its base and in terms of its rhythmic grounding, it was definitely

in another place. It was not jazz. Of course, audiences didn't really

like it, but that didn't bother Braxton at all because he was hearing

this stuff. He liked that stuff. He was going in his direction and that

is a wonderful thing.

FJ: Let's touch on the various bands you have led through the years, first,

the Slickaphonics Band.

RAY

ANDERSON: Well, it is a cooperative band and so I was never the band's

leader. As a cooperative, it had a wonderful kind of just groove quality.

It just grooved. We were hanging out and we had this little jam session

going on every week in Jim Payne's apartment and gradually, that group

of people that became the Slickaphonics were the people that were there

all the time and it got to be really fun and then people started bringing

in little charts and ideas and compositions and we started trying them.

That was back in '79, around 1980, when we were doing that and there was

this punk rock explosion in New York and a whole bunch of little clubs

opened. So we got the idea of, "What the heck, let's take this in one

of these. We could get a gig there. Why not?" We didn't even have a name

for it then, but then we had to have a name so the Slickaphonics came

from me from a composition I had written.

FJ:

And did you get gigs?

RAY

ANDERSON: Yeah! We started doing a bunch of gigs. And then two things

happened. Somebody heard us and said something to somebody and we got

invited to the Berlin Jazz Festival. That was one thing and then another

thing is, we got connected to Enja Records, so suddenly, the thing got

a lot more serious. We had this Berlin Jazz Festival gig and we had this

Enja Records thing, so we made a record and we did this gig and it was

really, really successful and then the thing was kind of off and rolling.

It was my major commitment for quite a bit of the Eighties. We did a lot

of touring and a lot of gigs. It was a wonderful band.

FJ:

And the Alligatory Band?

RAY

ANDERSON: When I quite the Slickaphonics, I made a lot of records and

did a lot of work in the standard jazz quartet form, which is a form I

still keep around to this day. I either use piano or guitar and then bass

and drums. It is just a trombone led quartet. There is a bunch of records

like that. It Just So Happens is a record like that and a few other people

on it. Every One of Us is a record like that. Then there was Old Bottles,

New Wine, that is a record like that. A bunch of these are not available

anymore. So I did that for a while and then I got into the Alligatory

thing. The first difference between the Alligatory band and the Slickaphonics

thing was first, it was my band and so I was the composer, which gave

it a lot more personal focus. The Slickphonics, everybody was involved

in it. We had compositions that covered a really wide range of different

concepts and for a while, that worked well, but eventually, people were

just going in different directions. Compositionally, that is a big difference,

but then the Alligatory with percussions as well as bass, guitar, and

drums, and also trumpet with the trombone had a really different sound.

The Slickaphonics was tenor saxophone and trombone and guitar and bass

and drums and I played some percussion when I wasn't playing the trombone,

but I was pretty busy in that band, so in the Alligatory thing, I had

a full time percussionist, which gave us a lot fuller sound in terms of

working with Latin rhythms or different kind of funk rhythms. I was able

to do more with that stuff than the Slicks ever could do.

FJ:

And the Pocket Brass Band, which has a new album on Enja, Where Home Is.

RAY

ANDERSON: Lew (Lew Soloff) was in the Alligatory. I'm proud of it, actually.

I really liked the way it came out. We were on tour when we made that

record and that's a great thing because that band had been working every

night for some seven or eight nights and then we went in the studio. It

was recorded in Switzerland. We were on tour in Europe. So that meant

that we were really, it was like a live record in some ways. We went in

this little, tiny studio where we all just stood up and played in the

same rooms without headphones or any of that kind of sound division stuff.

It really has a live performance feel and that is a great thing.

FJ:

Getting the material down on tour helps.

RAY

ANDERSON: Yeah, it is great to do that because you can have a bunch of

rehearsals and go into the studio, but when you've been playing this stuff

for an audience every night, you know more about it. You know more about

those tunes if you have been performing them. We were well rehearsed (laughing).

FJ:

Your vocal escapades have been a lightning rod for much of your recent

endeavors. The media seems to have a distinct problem with your singing.

RAY

ANDERSON: Yeah, I find it really interesting that you would say that,

Fred, because I haven't been able to figure it out either. It does seem

that the media hates my vocals, not all the media of course, but it is

true, by in large, I get really good reviews for my trombone playing and

band leading abilities and really bad reviews for my singing (laughing).

It is weird to me too because it always feels as if they feel that I'm

not staying in the slot that I am supposed to be in and that is irritating

because I do come from trying to express myself in whatever way I can.

So I don't sing just to be singing, but because I actually have some lyrics

that I want to put out into the world. I am taking it seriously. I'm trying

to do something with that. I've never been able to quite figure it out.

What's really funny about it is, that the audience just loves it. As much

as the critics hate it, the audience loves it. The audience always comes

up and says, "Boy, you really ought to sing more." "Boy, you have a nice

voice." I don't know what to do with it to tell you the truth, Fred.

FJ:

Always listen to the people.

RAY

ANDERSON: OK, thanks, Fred. I appreciate the vote of confidence.

FJ:

Your approach to the trombone is not limited to the instrument, but rather

you have transcended it almost as if it were a saxophone.

RAY

ANDERSON: Thank you, yeah, exactly. When I was a kid, and I was really

a kid because I started when I was eight, so when I was nine, ten, eleven,

twelve, I was very into jazz and I just really wanted to sound like Dizzy

Gillespie or Coleman Hawkins or somebody. I didn't really want to sound

like J. J. (J. J. Johnson). As much as J. J. trombonistically is just

unbelievable, incredible, monster, there was something about the fleetness

of the way that Dizzy could just bounce and fly or the way Bird could,

or Coleman Hawkins, or Sonny Rollins. I was more possessed by that stuff.

And then the thing that was really a gift was, once I did grow up and

learn some of what the AACM and the Art Ensemble of Chicago and those

cats, where they took the music, to go open and freer like that enabled

me to find a voice that I would never have found if I was still trying

to play "Shadow of Your Smile" or something. If you can find a voice like

that, then you can come back and play "Shadow of Your Smile" and make

it your own. So it is true, now when I play the trombone, I don't think

about the notes. It is sort of like singing, I don't think about the pitch.

I just play.

FJ:

And the future?

RAY

ANDERSON: Well, I made a really wonderful tape with Matt Wilson on drums

and Mark Helias on the bass and a guitar player that you don't know and

I really want to put this out. It's a live record from a gig we did close

by my house, here in Long Island. It is a gas. It is such a good band.

That is recorded and I don't have a label for it. I am trying to figure

out what to do and I haven't figured it out yet. I don't know whether

to go one hundred percent my own route and put this thing out or whether

I can link it up to some other distribution company. That thing will come

out. We call it Bone Meal. That is on tap.

Fred Jung is Jazz Weekly's Editor-In-Chief and Fire Starter. Comments? Email Fred.