photo by H.K. Millar

A

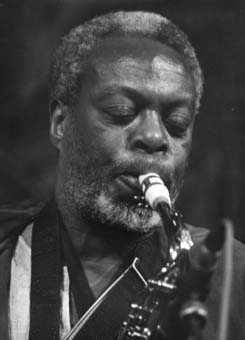

FIRESIDE CHAT WITH DEWEY REDMAN

Anyone who has worked with Ornette Coleman and Keith

Jarrett is a Roadshow superhero. Dewey Redman has done both, so the Fireside

chair is marked reserved for the tenor saxophonist. Redman was diagnosed

as having prostate cancer a few years ago. He is in remission now, but

as fans, we should all be grateful for every performance and every recording

from one of jazz's most under-recognized voices. I am honored to present

to you, Dewey Redman (father to one Joshua Redman), unedited and in his

own words.

FRED JUNG: Let's start from the beginning.

DEWEY REDMAN: I have always been interested in the music since I was a

kid. I used to sneak out of the house at night to go listen to bands that

came though. There were no concerts. There were only dances, but I heard

a lot of the old timers, people that you wouldn't know. And so my interest

grew in music until I was about twelve, thirteen and I decided that I

wanted to play music and I didn't know what I wanted to play. So I knew

I didn't want to play trombone because it was too much exercise. The piano

had too many notes. So I finally figured out that what I really wanted

to play was the trumpet because it only had three keys. I went to my teacher.

I went to a teacher and he was a brother and he said, "You can't

play trumpet because your lips are too big." I was embarrassed and

discouraged, but I found out later that he needed clarinet players because

there was a church band that he was in charge of and nobody wanted to

play the clarinet because it squeaked and so that was the reason that

he told me this, but I never forgot it. And so my first gig was in a church

and from then on, I was in high school. I played in the high school band

and my interest in jazz was still there. There was a friend who had some

Charlie Parker records when Bird first came out, whom I didn't like at

all. But since, I have learned that he was the greatest improviser that

I've ever heard. I went through college. I guess I am telling you my life

story, Fred (laughing). Anyway, I went to Prairie View A&M, which

is in Texas. I'm from Texas, you know, Fort Worth. My interest in jazz,

I played in a jazz band, a college jazz band and then my interest was

still in this music. And so after college, I was drafted into the Army

and I never got out of Texas. I went to El Paso, Texas and I stayed there

for two years and I met a wonderful gentleman, who taught me a lot about

jazz. Then I went back to Texas and I taught school for four years in

Texas, in a small town near Austin, Texas and then on the weekends, I

would go to Austin and play in bands. And everybody said, "Hey, man,

you sound good. You ought to be in the big time." I thought about

it a couple of years and then I decided to go to New York, stay five years,

get it out of my system, and then come back to Texas and teach school.

However, it didn't work out like that. I've been in New York thirty-three

years and the five-year plan just went to hell. Actually, when I left

Texas, I went to California to find my father and that's another story

and I finally found him because I hadn't seen him in fifteen years. Then,

I am on the way to New York. I didn't like the Los Angeles scene because

there was nothing happening. I'm on the way to New York and somebody says,

"Go to San Francisco. You might like it there a little better."

And so I went to San Francisco for two weeks and stayed almost seven years.

FJ: You seemed to get sidetracked a good deal.

DEWEY REDMAN: (Laughing) Yeah, but it was a nice community. I was there

in the Sixties. It turned out to be, probably, one of the best places

in America to be. Not only did they have the flower children and the protests

against the Vietnam War and the love ins and the smoke ins and all of

the other ins, they had a nice jazz community. It was a very interesting

place to be. I almost forgot about New York. As a matter of fact, Fred,

I used to see, there was the Haight-Ashbury district, but I used to see

Janis Joplin walking down the street. It was the beginning of Jefferson

Airplane and Country Joe & the Fish and The Grateful Dead and all

of that. I didn't realize it at the time, but it was historic. Of course,

the jazz community was good. I got a chance to play and it was great.

It was much better than Los Angeles. And then, after about seven year,

almost seven years, I decided that it was time for me to go to New York.

FJ: San Francisco's vibrant culture was emerging, why leave a sure thing

for the lure of bright lights, big city?

DEWEY REDMAN: Well, it was time because my original plan was to go from

Texas to New York. I was on a five-year plan. I was going to go from Texas

to New York, spend five years there, get it out of my system, and come

back to Texas. And so I arrived in New York in 1967 and I was thirty-four

years old and had never been to New York before, but I knew Ornette Coleman.

I had kept up with his music all this time and so he said, "When

you come to New York, come to my house." He had a loft in SoHo and

so I went to Ornette's loft and he said, "Bring your horn over."

And so I brought my horn over and we just started playing some of his

tunes that he wrote. He is a prolific writer. He can write ten tunes in

ten minutes. It takes me ten years. Anyway, that was the beginning of

my jazz career in New York thirty-two years ago. So I played with Ornette

and within a year, I was playing with Ornette Coleman. It was a great

job to me because nobody knew who I was. Here I was playing with one of

the best known artists in the world. Then I started playing with Keith

Jarrett. I played with Pat Metheny and many, many others, Old and New

Dreams, Charlie Haden & the Liberation Music Orchestra, Carla Bley.

Anyway, that is pretty much it up until now. But I have also had my own

bands.

FJ: What was it about the Big Apple that had you abandoning the five-year

plan?

DEWEY REDMAN: Well, the first thing, I had to go find my father that I

hadn't seen or heard from in about fifteen years. So that was important

to me and I knew that he was in the Los Angeles area, so I went to Los

Angeles and I found him. It took me about three or four months because,

actually, when I found him, he was dying. He was in the hospital, but

I got a chance to see him before he passed. And then, it was on to New

York, but San Francisco got in the way. And the real reason that I stayed

there for a long time was that I had always played by ear. I didn't know

anything about chord changes or two, five, one and all that. What I did

was the last two years that I stayed in San Francisco, I rented a piano

and learned about chords and changes and all of that on the piano. It

was a great help to me because I knew that if I went to New York, I couldn't

go to New York just playing by ear. I had to verse myself in the harmonic

side of music and the technical side because you can't be in New York,

you have to know damn near everything, even though I still played by ear

mostly.

FJ: Even to this day?

DEWEY REDMAN: Even to this day. I can hear. I have relative pitch. I don't

have perfect pitch. I can play. I can still play a couple of notes.

FJ: What subject did you teach?

DEWEY REDMAN: I was a fifth grade homeroom teacher. I was also hired as

the band director because I had minored in music in college. I majored

in something else. But I was hired primarily to be the band director in

a small town. It is a very hard job because we had to practice after school.

But I had a fifth grade homeroom, so I taught spelling, geography, I don't

remember, Fred, because it's been so long ago now. But I had two or three

subjects that I taught in the fifth grade.

FJ: Do you miss bestowing knowledge to the youth?

DEWEY REDMAN: Teaching, oh, there is nothing like teaching. Yes, I miss

it, Fred, very much. I learned more from the kids than they did from me

(laughing) really, about human behavior. The kids are very hip. Kids are

very hip and I was always honest with them. I didn't try to be Mr. Big

Shot or the great teacher. I interacted with them, but they knew that

I was the teacher. I was honest with them and I think that is one of the

greatest attributes you can have being a teacher is to be honest with

your kids and let them know that you're honest, that you're human too.

So I enjoyed it, Fred, and I miss it. And it's been so long ago. I still

teach. I give private lessons, but it is nothing like teaching in school.

FJ: Here you are, first time in New York and you find yourself sharing

the same bandstand with Ornette Coleman, who at the time was an icon in

the big city. Nice.

DEWEY REDMAN: You better believe it (laughing). You better believe it,

even though he was a friend. I knew Ornette in high school. We went to

the same high school. Of course, in that era, all the black kids, I don't

care where you lived, had to go to the same high school. I knew Ornette

when he first started playing. First, he started playing like Louis Jordan.

He began to play like Louis Jordan, he and another guy named Prince Lasha.

Then he progressed through Bird and then he started the beginnings of

playing like Ornette plays. We never thought it was that different. It

was just the way Ornette played. It was accepted. Then he left Fort Worth

and went to Los Angeles, where he stayed for a long time, over ten years

before coming to New York. But it was a big thrill for me because knowing

the history of Ornette, when Ornette came to New York in 1959, he exploded

on the scene. You can imagine the outrage that he created in the jazz

community. The beboppers didn't like him. There was a great controversy

about Ornette. Whether this was jazz or even if it was music. He created

quite a controversy in 1959 and when I got to New York in 1967, there

was still, as a matter of fact, Fred, to this day, there are some people

who do not accept Ornette. I think he's a genius and I don't that word

lightly.

FJ: It has been over forty years since Ornette kicked the jazz world in

the back of the head, why the debate?

DEWEY REDMAN: Because he had no, I mean, all the jazz music up to that

point had bar lines. It had certain chords that you played on. That was

the way it was. When Ornette hit the scene, he had no bar lines. There

were no chords to play on. You really had to be creative. The heart and

soul of jazz to me is improvisation. We might play the same horn, but

we don't sound a like. There is nobody else that I know that's ever really

captured Charlie Parker or John Coltrane or even Ornette. So his forte

was improvising. He would write out a melody and then you would just improvise

on it. You didn't have to play chord changes.

FJ: When I listen to both Love Call and New York is Now on Blue Note,

Crisis on Impulse!, Science Fiction on Columbia, and Live at Prince Street

available through BMG International, your tenor playing flawlessly compliments

Ornette's playing.

DEWEY REDMAN: Well, it's just that whoever I play with, I try to, not

only just play the music, but integrate myself into their sound because

it was much different playing with Ornette than playing with Keith Jarrett.

It required a different whatever that is. It is really difficult to put

music into words, Fred, as you probably know. But it was a joy playing

with him. And then, I didn't have to worry about chord changes or all

of that. It was just great. I could just improvise and evidently, he liked

the way I played and improvised. I played with him and we made quite a

few records.

FJ: You made up the frontline of Keith Jarrett's vital quartet and quintet

in the Seventies, making numerous recordings, principally for the Impulse!

label, with the pianist that were liberal for their time.

DEWEY REDMAN: I met Keith through Charlie Haden because Charlie Haden

was playing in the band at the time in Keith's trio and he suggested me

to Keith and so that's how I started playing with Keith. I played a gig

with him and he said, "OK, do you want to be in my band?" I

said, "Yeah," and so that is how that started. And I played

with Keith for maybe three or four years.

FJ: For a major player in the avant-garde, you have recorded barely over

a dozen records in thirty-five years. Why have you not recorded more?

DEWEY REDMAN: Because, well, the main reason is that I never wanted to

record six records a year. I didn't think that I had that much to say.

But I am very proud of every record that I have ever recorded from the

first one in 1966 called Look for the Black Star (Freedom) up until the

present. I am very proud of every record that I have ever recorded, which

is about eleven at this point, twelve, I am not sure. And then there was

the thing with the record companies. It's always a hassle with the record

companies. You don't have to always go to them on bended knees and suck

up to the record companies. And I never did that. I don't know, Fred.

That is the way it worked out. I never regret it. I know some guys who

recorded a hell of a lot, but sometimes, if you listen to them, most of

them sound just the same. But with my records, I tried to play a variety

of things. On all of my records, I try to play a variety of styles. They

don't all come off, but that is what I do. That is what I try to do.

FJ: Your debut on Freedom, Look for the Black Star, features the late

drummer Eddie Moore, a terribly overlooked musician.

DEWEY REDMAN: We were friends too. Eddie and I played together for close

to twenty-five years, on and off together. Eddie played with Sonny Rollins

for a number of years and with Stanley Turrentine and with Ahmad Jamal

and many others. Basically, during the latter part of his career, he played

with me mostly. Eddie was a fantastic drummer. It was just fantastic.

Like I said, Fred, it is hard to put music into words, but we were also

friends.

FJ: As in the case of Eddie Moore, you also featured significant, yet

unheralded, violinist Leroy Jenkins on The Ear of the Behearer (Impulse!).

DEWEY REDMAN: Well, it is not the instrument. It is not what you play.

It is how you play it. To me, that's important and so I knew Leroy and

also, I knew Jane Robertson. She plays cello on the record. But I've always

tried to incorporate the player that I would thought would add to the

music the best, whether they played violin or piano or whatever.

FJ: So rather than focus on instrumentation, you center on the player.

DEWEY REDMAN: It doesn't matter to me what tune you play. It matters to

me how you play it.

FJ: Palmetto released an outstanding live set from you entitled In London.

DEWEY REDMAN: Yeah, live In London, which I think is one of my best. I

think it is one of the best. Actually, all of it wasn't live. We recorded

some in the daytime and then some at night. So I have some more from that

recording session that I haven't put out yet.

FJ: Do you plan on releasing another volume?

DEWEY REDMAN: Yeah, in the future, yeah. As a matter of fact, Fred, I

recorded this January another album that I haven't gotten around to putting

out yet because I've been so busy. In the meantime, I have contracted

prostate cancer, so I've been living with that for three years. As a matter

of fact, last year, I gave the First Annual Jazz for Prostate Cancer Research

Benefit in New York and the musicians gave their time and we did it at

the Knitting Factory. We're going to do it again this year. The Knitting

Factory gave us the space and we were able to raise almost five thousand

dollars that we turned over to the American Cancer Society for research

into prostate cancer because it is devastating our neighborhood. You know

African-American are three times the rate of Caucasian men when it comes

to prostate cancer.

FJ: What seems to be the reason behind the numbers?

DEWEY REDMAN: The only reason that the doctors know is, when I got it,

I didn't even know that I had it. I had none of the symptoms or anything.

That is a long story, but to make it short, the only reason they know

is because African-American men don't go get checked up. It is not necessarily

genetic, but I think maybe ten percent of all cancers are genetic, is

that we don't go and we don't want to go. We don't know and we don't want

to know. And by the time we get there, sometimes it is economic. We don't

have the resources to go to the doctor. So that is the only reason they

know and that is the only reason I know. I'm active in my neighborhood

especially because up to forty thousand men are going to die from prostate

cancer this year. Last year, unfortunately or fortunately, we had some

high profile people in New York, including the mayor, who came down with

prostate cancer and the chief of police and some other high profile people.

But also, in the black community, when I researched this and I was trying

to put this show on, I found out that there was a lot of jazz musicians

who have prostate cancer including Kenny Burrell, J. J. Johnson, the Heath

brothers, Jimmy and Percy. There is a long list of jazz musicians who

have prostate cancer, I found out in trying to get this program together.

I feel I have to give something back.

FJ: How are you holding up?

DEWEY REDMAN: I feel OK. I'm not cured, Fred. I'm just in remission. I

feel glad that I'm here. When I was diagnosed, I went to the doctor and

they take a PSA and that is a blood count and on the scale of zero to

four, four being the highest, my PSA, my second opinion was two hundred

and eight. The doctor told me that on the scale of one to ten, you have

at least a seven of prostate cancer. It shocked the hell out of me because

I had none of the symptoms. The symptoms are you pee a lot or you have

lower back pain or you can't pee. Those are the symptoms. So I had none

of the symptoms. That is another story, but I am looking forward to giving

the Second Annual Jazz Prostate Cancer Research Benefit in New York this

summer some time. A couple of months ago, I was stricken with pneumonia.

FJ: You're like Job.

DEWEY REDMAN: Yeah, man, you ever had it?

FJ: No.

DEWEY REDMAN: You don't want it. I've never been so sick in my life, Fred.

I'd just played a gig in Tel Aviv and came back and so I got sick and

my muscles were aching and I was coughing and I went to the doctor and

they rushed me to the hospital quick in an ambulance and found out that

I had pneumonia. It's been a couple of months, but I feel OK now.

FJ: A couple of years ago, remarkably, Verve released Momentum Space,

a session coupling you with Cecil Taylor and Elvin Jones. Has Verve expressed

any interest in a second volume?

DEWEY REDMAN: No, I don't. It would be nice but no I don't think so.

FJ: What label will be releasing your new record?

DEWEY REDMAN: I'm in the process of getting my own label. The live In

London was the last really one that was put out, well, Momentum Space

was on Verve. But I decided that, I mean, it is very difficult to find

a record company unless you are a big, big star. If you are a big star

then there is no problem. But if you are not a big star and you don't

sell a lot of records, then, like, there is another member of my family,

I can't think of his name now, that is very, he's a superstar. Uh, I can't

think of his name right now (laughing). But if you are in that category,

then there is no problem, but for, not only me, but for a lot of other

lesser known jazz musicians, it is a real struggle and the way things

are going now, why not? It seems that with this Napster business and people

just taking music, why not have your own label? It is not that difficult

to get a CD printed. So that is what I decided to do. So hopefully, this

next record will be on my label.

FJ: As a father you must be proud of Joshua's success.

DEWEY REDMAN: Oh, extremely proud, although, he sometimes doesn't mention

me in his interviews (laughing). I'm extremely proud of him and he is

a nice young man and he's a fantastic player. I'm better, but he's, I'm

very proud of him.

FJ: Final thoughts?

DEWEY REDMAN: One other thing, Fred. The way that I approach music is

through sound. I figured that if I had a good sound, that would get me

half way there, maybe more than half way. So everything I play, I try

to play with a good sound. That is very important to me. That's the first

thing on my list, is to play with a good sound. One day I sat down and

figured out that everybody I liked, whether they played drums or piano

or sang or whatever, what I liked about them was they had a good sound

and so that has been my approach to music.

Fred Jung is the weakest link. Good-Bye. Email

Him.